Sharwil is Australia’s most important contribution to the world of avocados. It’s an exquisite fruit that has impressed all from the start. In 1961, Stanley Shepard, a leader of the California avocado industry, visited the continent down under and reported: “The most promising Australian fruit that I saw was the Sharwil.”

Fruit characteristics

To my taste, Sharwil avocados are just right. They are medium size, not too big and not too small. Their skin is green, whether ripe or unripe, and it is medium in thickness, not thin enough to split while on the tree like Stewart and not too thick so it’s hard to tell when they’re ripe like Nabal. And the skin is bumpy, and it peels well.

Inside, the flesh has no fiber; it is green and golden yellow. The flavor is neither weak nor strong, it is just a good avocado flavor, similar to Hass or Fuerte. But usually the flavor is slightly milder than those, more like the flavor of Edranol.

Where Sharwil rises above is with its small seed, smaller than Hass or Fuerte or Edranol.

Harvest season

The earliest I have eaten a good Sharwil is February, and the latest is May. This is for fruit grown in inland San Diego County. For comparison to other varieties grown in this same region, Sharwil tastes good later than Fuerte but earlier than Hass.

When W.B. Storey took a trip to Australia in 1960 and observed Sharwil for the first time, he reported back to fellow Californians: “This appears to be a very fine fruit which matures later than Fuerte and about the same time as Hass.”

But in 1960, Sharwil was a very new introduction, and only one year later an Australian named George Schulz wrote that the Sharwil harvest was “just before the Hass.” Sharwil was still being figured out then.

Variety history

Sharwil is the creation of Frank Sharpe, who was a pioneer of avocado farming in Australia, starting near Brisbane in 1946. Sharpe grew local varieties but also imported trees of all the best California varieties from Armstrong Nursery, then based in Ontario, San Bernardino County. And from the beginning he grew out seedlings in search of improved varieties. In 1954, he introduced the Sharwil, which he had crossed at his Redland Bay farm in 1948-49.

The parents of Sharwil are unknown, but if you’ll allow me to speculate . . . I think that Edranol is one of them. The leaves of the trees of the two varieties have a similar spade-like shape. The fruit of the two varieties have similar skin color, thickness, and pliability; the flesh of both is fiberless and tastes similar; and the seeds of both varieties have a tendency to hold onto a little flesh when the fruit is cut open. Further, Sharpe lists Edranol as one of the main varieties he grew on his Redland Bay farm at the time he grew the seedling that became the mother Sharwil, and no other of his listed varieties bear as much resemblance.

“Sharwil” is a portmanteau, combining the names Sharpe and Wilson. James Wilson was in a farming partnership with Frank Sharpe, and he later bought from Sharpe the Redland Bay farm where the variety originally grew.

In the 1950’s, Sharwil was brought to California but, as Stanley Shepard of Carpinteria wrote in 1970, here “it does not seem to do as well as it [does] in other parts of the world.”

In 1977 in Queensland, three varieties dominated avocado plantings: Fuerte, Hass, and Sharwil.

But by 1990, Sharwil was “losing popularity among growers in most areas [of Australia] because of erratic production,” wrote D.W. Lavers.

Investigations into the erratic production of Sharwil in Australia turned up an explanation that had been known for decades. Sharwil has a B-type flower, and B types are generally less productive in some climates than A types because they are more sensitive to cool temperatures during flowering. (See also Peterson, 1965.)

Sharwil doesn’t have this problem where nights are warm, such as in tropical areas. On Hawaii’s Big Island, particularly in the Kona district, Sharwil became the variety that avocado farmers chose for commercial production and export starting in the 1980’s. Unfortunately, from then until today, the USDA has gotten in their way and banned the movement of Sharwils from Hawaii to the mainland on and off through fruit fly regulations.

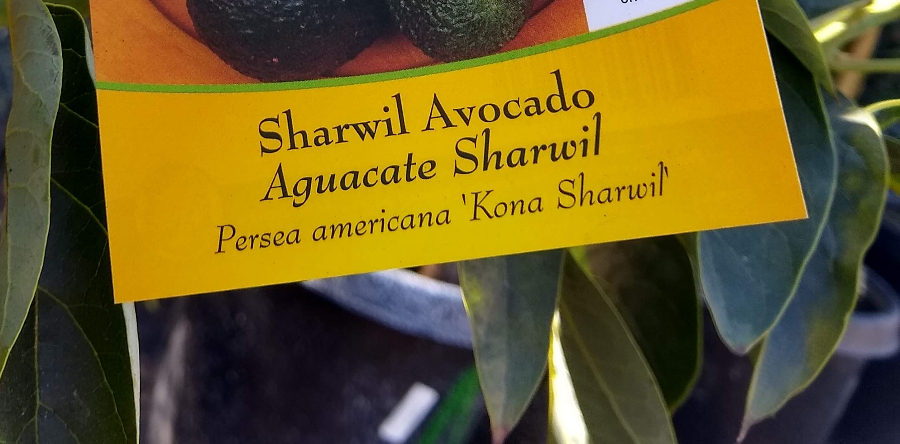

Nevertheless, the association of the Sharwil variety with the Kona district became strong enough for some growers and nurseries in California to start referring to the variety as “Kona Sharwil.”

The irony is that I’ve never heard a grower in Hawaii refer to the variety that way.

(See McDonald, 2010 and Bevacqua, 1994 and Hawaii Avocado Association.)

Sharwil avocado tree characteristics

Leaves and stems

I don’t have firsthand experience with Sharwil trees in Hawaii or Australia, but I do have firsthand experience with them in California. I’ve grown a handful of my own, and I’ve seen many more elsewhere.

Sharwil trees have gorgeous foliage, with large leaves that are deep green. They are prettier than many other varieties to me, as pretty as a Bacon.

The young stems have red flecks, especially if they’re growing rapidly such as on a tree that has been grafted to a large rootstock.

The leaves of Sharwil do not smell of anise if crushed, as the leaves of some other avocado varieties do.

Architecture

Sharwil trees have spreading canopies; they’re not drooping like GEM nor are they upright like Zutano. They grow similarly to Hass, except that they more often send out long branches that later sag, especially if they’re carrying fruit.

Sharwil’s canopy shape is partly due to the fact that its branches don’t make as many side branches as some other varieties. Trees that make branches with many side branches (“sylleptic” growth) look more dense and are less vulnerable to sunburn. Reed, Edranol, Cadway, Carmen, and Gwen are examples of varieties with much sylleptic growth, denser canopies, and less sunburn vulnerability compared to Sharwil.

(See an academic analysis of this tree architecture topic by Thorp and Sedgley.)

Sharwil’s branch architecture is not a problem in a mild climate, such as one near the beach. But it is annoying to a grower in a location with strong sun, as it requires one to frequently cut short such long branches (“head” them) or else accept sunburn, which will later impair the vigor and productivity of the sunburned branch.

Heat and cold tolerance

In this way, Sharwil is not as suited to locations with hot summers as well as some other varieties. (This isn’t to say that Sharwil can’t be grown successfully in a hot climate though.)

In terms of cold tolerance, I have found Sharwil to be no weaker or tougher than Hass.

Productivity

The Sharwil tree’s fruitfulness is the most important quality to consider. Here in California, Sharwil is simply hit-and-miss.

First, some young Sharwil trees are slow to begin making avocados. I have one that is six years old and yet has barely made flowers and has not produced a single fruit whereas I have trees of other varieties of the same age that have already made dozens. I have heard reports from others with similarly indolent Sharwils.

But I do know of a few young Sharwils that have produced, and I have seen Sharwil trees that were made by grafting onto mature rootstocks and some of those trees set good crops within two years of grafting.

Sharwil’s fruitfulness is most closely related to where it is growing. As mentioned above, Sharwil has a B-type flower, which needs warmer weather to make fruit compared to A types.

(Sedgley and Grant published a study on this phenomenon in 1983.)

Therefore, if a Sharwil tree is grown in a cool location, it is unlikely to produce as much fruit through the years compared to most A types. And a Sharwil tree will not produce much fruit in a given year if that year has weather that is too cool in spring, no matter the location. (The past two springs, 2023 and 2024, have been cooler than average in Southern California, especially 2023.)

An illustration of this is seen in an avocado tree that I have with a dozen or so varieties grafted on, including Sharwil. During this past cool spring of 2024, the Sharwil branches flowered heavily but did not set a single fruit. At the same time, some other B varieties flowered well and they also did not set any fruit. On the other hand, most of the A varieties set fruit, and some set so much that I had to thin their branches to prevent them from breaking.

But to reiterate, Sharwil’s fruitfulness depends a lot on the location. During this same cool spring of 2024, this Sharwil tree in a warmer location about ten miles from me performed quite differently:

Should you grow a Sharwil tree in your yard?

I would not choose Sharwil as my yard’s only avocado tree. I would choose a more reliable fruiter for that, such as Hass or Reed. But if I had space for multiple trees I would add Sharwil, especially if my yard were warm enough to get good production from a B-type avocado.

How to know if your yard is warm enough? If you see frost on the ground in your yard many times every winter, then it’s not best for Sharwil or any other B type. (Here is a presentation on the topic that gives more specific information.)

Sharwil can make a nice addition to a yard’s avocado trees because it fills the harvest window of late winter into spring. I know of no other variety that is as enjoyable to eat during this window.

Sharwil’s legacy

Sharwil is not grown much commercially in Australia anymore. Sharwil never impacted the commercial avocado industry in California. Yet Sharwil has been in high demand from backyard growers in California for the past decade or two primarily because of the influence of members of the Orange County chapter of the California Rare Fruit Growers. They shared about the virtues of the Sharwil fruit and they grafted Sharwil trees to spread around.

I would guess that here in 2024 there are more Sharwil avocado trees growing in California dirt than ever before, 80 years after the variety was first brought to American shores, even though almost none of them are growing on farms.

Some avocado breeders have tried to develop a tree with a Sharwil-like fruit that produces better. Even though Sharwil produces relatively well in Hawaii, breeders at the University of Hawaii aimed toward better production with their release of a seedling of Sharwil they called Greengold. Although Greengold has an A flower and fruits more in some of the trees I’ve seen, I don’t think the Greengold avocado quite reaches the heights of Sharwil eating quality.

David and Judi Grey of New Zealand have selected three seedlings of Sharwil from a 1999 planting that they call the “Avogrey” varieties. Each is a greenskin, and it is said that they are of good eating quality and produce “regular crops.”

Perhaps the Greys have landed on an improved Sharwil. We can hope. (I have not eaten these varieties nor seen the trees in person.)

For now, we will be grateful for how good Sharwil avocados are to eat whenever the trees bless us with them.

My video profiles of the Sharwil avocado:

And the Sharwil tree:

If you get value from this profile of Sharwil, consider sending some value my way. I spent time and effort and money putting it together for you. Thank you, Greg.

Hello Sir!

Would Sir Prize not be ripening around the late winter/ early spring? If so I am going to have a ton of them! Also Bacon Hass and Fuerte. I want to find the perfect time and pick all of them at once (maybe late bacon and early hass). Around that time I will let you know and come by and do a taste test.

Thank you for the deep dive on sharwil. You are ahead of the curve, as always!

Nick G

Yes, yes, yes, Nick! I checked a bunch of my notes and found that the harvest season of Sir-Prize is almost the same as Sharwil (for avocados picked from trees at the same location), with Sharwil usually hanging with quality a little later.

My 3 yr old Sharwil has some 15 fruit. Live in Rolling Hills Estates where temps can be warm with little to no frost.

John T

I planted a Reed, Gem, and Sharwil simultaneously in Santa Barbara three years ago. The first two are very happy, leafy, and bushy.

The Sharwil, as you said, is spindly; I’ve had to paint the whole thing white to protect it from sunburn.

Oddly, despite the cool Spring, it decided to set some fruit for the first time this year… but it hasn’t made a single flush of new leaves or branches. Growth-wise it just seems to be frozen.

Should I remove the fruit? Is there anything else that causes and avocado tree to go into stasis like that? Its two neighbors are clearly happy with the same soil and watering schedule.

Hi Andreas,

I would remove fruit in that situation. Lots of things can make an avocado tree unhappy, but most of them occur around the roots so my first inclination is always to scratch and dig down there.

Love the avocado knowledge as always! (written while waiting for the Reed you sent to ripen)

Greg, I have Reed and Gwen tree in my yard and I have room for one more (trying the avo hedge on 12’ centers) was thinking about Sharwil or Sir prize, any advice on which one to try? I’m in Sierra Madre CA (above Pasadena) so it’s hot and most years are frost free.

Hi Doug,

Both Sharwil and Sir-Prize would be good additions. They’re both delicious avocados, but both are a little quirky in production. Sir-Prize can produce tons but usually doesn’t start in its first few years.

The fruit of Sharwil is a tad better than Sir-Prize, I’d say. And Sir-Prize avocados turn black whereas Sharwils stay green. The Sharwil tree grows a little bit faster and stronger and wider, as Sir-Prize branches are a little weaker and more weepy although some will grow upright at first.

But the differences are very minor. I would be very happy to have both trees, and both should do well in Sierra Madre.

Okay Greg and anyone that would like to spread the love, here’s the deal, I am hell bent on getting a Nabal. Our family had one for 51 years. The taste is perfect.

So, since the Nabal is a free spirit as far as fruiting what would you suggest as my second avocado tree that is more on schedule and on a different schedule than the Nabal for picking? (To cover most of the year with avocado eating thing) What I like are no strings and gray spots.

Oh and would you try and talk me into getting a Reed instead of Nabal? I would consider doing this, if you said so 🙂

FYI- I am in San Diego, Ca. 10 mins inland.

Last question, do Avocado trees do okay near Eucalyptus? If so, would it like some canopy over it to stave off sunburn?

Thanks!

Hi Allison,

Nabal is a nice avocado, but from all that I’ve seen Reed is a little better. It fruits more consistently, its skin is a little thinner so it is easier to tell when it’s ripe, and the Reed tree is more compact (which I like).

The harvest season of Nabal is a bit earlier than Reed, but for either one I would choose a complementary variety that harvests before them. So I’d consider Fuerte, Hass, or Sharwil. There are many other good ones too. Your location should get good production from B types like Nabal, Fuerte, and Sharwil, just as you should get good production from the A types like Reed and Hass.

Avocado trees are wimps; eucalyptus trees are aggressive, tough guys. An avocado tree planted near a eucalyptus tree is not ideal, but I’ve done it and seen it done elsewhere. It can be done. What happens is the eucalyptus roots find the water you’re giving the avocado and start stealing it so you have to make sure to give the avocado extra water as necessary.

No need for protection from sunburn in your location.

If you haven’t already found a Nabal, check with Eli’s Farms/Subtropica Nursery in Fallbrook. I bought one earlier this year from them.

Thanks so much for replying :))

I have more questions now. I hope that’s okay?

Now I have watched your vids but it hard to keep it all in my head. Awesome videos by the way.

Does Reed taste as good as Nabal in your opinion? Much different? Is a large Reed easier to find than Nabal? I have only found one 7 ft Nabal in Rancho Cucamonga. (no truck)

For my earlier picking and eating 2nd Tree- I can’t stand strings, gray spots. Not into watery. Don’t care about size or outside/inside color, bumpy or not. Sharwil?

Should I be hiring you for consultation? To talk avocados and all the options? I feel kind of guilty asking so many questions. I really would like to nail this down and make it happen.

As far as Eucs go for sure they are water stealers! My rose beds, oh my, poor roses. (I’m thinking of planting the avacados in the rose beds. It may be a fight but at least I’m aware. lol) Our Euc is huge!

Thank you so much for your time!

What would be good avocado scions to graft on to a Mexicola tree? Also, what would be good avocado scions to graft on to a Fuerte tree? Thanks.

My backyard Fuerte tree would not produce fruit in my location in San Luis Obispo (but does in other locations in SLO). So in 2022 I graphed Hass and Sharwil on to a sucker from the Fuerte I removed. Now in spring 2025 I have my first crop of avocado to pick this spring (to fall for Hass). The tree produced about 30 Hass and 3 Sharwil avocado. The Sharwil only produced on the sunny side of the tree. I acquired the Sharwil Scion from the Orange County chapter of the California Rare Fruit Growers. Looking forward to what fruit set I get this spring. Just tasted my first Sharwil and it’s fantastic.

Hello,

I live on the East Coast, in New York City, and as you can imagine, I don’t have a lot of ground space. I’m currently growing other fruit trees and plants in containers, and I’m very interested in adding avocados to the mix. This would be my first time growing avocados.

I’m mostly interested in high-flavor varieties that aren’t available in grocery stores like Hass. So far, Gwen has stood out to me based on what I’ve read. I’m also looking for a type B avocado to eventually pair with it for better pollination. My plan is to keep the trees outdoors in the summer in a spot that gets only morning sun, and then bring them inside during the winter and early spring. Indoors, the environment will be regulated with grow lights and stable temperatures.

I understand this setup may limit fruiting, but I’m okay with a lighter harvest — just enough for a few bowls of guacamole each year. Eventually, when the trees are mature, I’d like to try grafting other varieties I’m interested in, such as Jan Boyce.

I’m having a hard time sourcing avocado trees on the East Coast, especially varieties beyond Hass. I wanted to ask if you think Sharwil would be a good option for someone in my situation — limited space, container growing, morning sun in summer, indoor growing with lights in winter, and a strong interest in flavor.

I’d also appreciate any suggestions for flavorful and compact type B varieties that might work well alongside Gwen or in a similar setup.

Thanks so much for your time and insight.

Hi Michaela,

I think Gwen is a good option for a container tree, as are GEM and maybe Lamb. As for a B type, there are no great options but Sharwil is as good as any. The problem with the B types is none are as compact and precocious as Gwen and GEM and Lamb while also making excellent fruit, except for the Luna variety, but Luna is not available to home growers yet.