Did you know that you live in Avocado Land? “The citizens of the Golden State can make a better claim for having ‘invented’ the avocado than anyone else,” writes Rob Crisell in the opening chapter of his new book California Avocados: A Delicious History.

I did not know this growing up because I, like Crisell, grew up in Avocado Land. I have no memories of first eating an avocado or climbing in a tree since they were always around. Nor did I ever think avocados were special. Nor did I know California was special to avocados.

Overview

In this book, Crisell walks us through the history of growing and marketing and eating avocados in California. To get to the meat of the story, he starts with botanical aspects of the avocado, such as the tree’s strange flowering habit, its wild origins in tropical latitudes of the Americas, the use of avocados by Mayans and other peoples native to that region, and the first impressions of avocados by exploring Europeans.

“Coming to America” is a chapter where Crisell details how avocados arrived in California around the time of the Civil War. The first commercial venture in avocado growing was started by Henry Huntington and William Hertrich in the early 1900’s near Pasadena. Also near Pasadena, the West India Gardens nursery funded exploration for superior varieties in Mexico that resulted in Carl Schmidt finding the Fuerte variety in 1911.

“Birth of an Industry” is the following chapter which talks about the founding of the California Avocado Society in 1915. The yearbooks produced by the Society form the bulk of all written history of avocado development worldwide over the last century, and Crisell could not have written his book without their aid. They were “an indispensable resource for me,” writes Crisell. The California Avocado Society remains the oldest avocado organization in the world.

We are introduced to pioneers of the budding California avocado industry. These pioneers include J.E. Coit, Edwin Hart, A.R. Rideout, D.W. Coolidge, and Fred and Wilson Popenoe. It was Wilson Popenoe who called avocados “God’s greatest gift to humanity.”

In the next chapters, Crisell tells us how the marketing of avocados was pursued and how the growing population of Southern California influenced the growing of avocados. Distinct growing areas with their own personalities arose and declined and changed epicenters. Los Angeles County was the initial nexus, and then Orange and San Diego Counties. But later, avocado growing in California morphed into a “North” (Ventura/Santa Barbara Counties) and a “South” (San Diego County) because the center of Los Angeles and Orange Counties became urbanized.

“Avocados Go Mainstream” covers the period 1960-1980. During this time, avocado acreage exploded, in part because of a law that gave people a tax credit for investments in avocado groves. (This law was repealed in 1976.) A law was also passed that made avocado growers pay a new tax (called an assessment) on their avocados so that an organization could advertise for avocados for them. This organization became what today is called the California Avocado Commission.

Advertisements were purchased in magazines and on television, sometimes in collaboration with processed food brands such as Doritos and Pepsi. Ironically, CAC also spent money marketing avocados as healthy during the anti-fat fad of the 1960’s.

Innovations in growing during this period included the introduction of drip irrigation, and the University of California, Riverside made contributions in many ways, including through the development of new varieties, Gwen being the best of that lot.

But the marketers desired to market only one variety: Hass. In the 1970’s, Hass surpassed Fuerte in market share and from then until today the California industry has only increased its commitment to Hass.

In the next two chapters, Crisell explores the ways in which California avocados have become World avocados. California growers and researchers had a hand in helping the development of avocado industries in other countries such as Spain, Israel, Australia, South Africa, Peru, Chile, and Mexico.

Today, California companies that started by handling (buying and selling) California avocados now make most of their money handling foreign avocados, especially Mexican avocados.

Mexican avocados were allowed to be sold in the U.S. starting only in the late 1990’s, but they soon flooded into the country. In 1998, 6.5 million pounds of avocados arrived into the U.S. from Mexico. Last year, in 2023, over 2 billion pounds of avocados from Mexico arrived into the U.S.

California Avocados gives the reader an understanding of the many players and dramas that took avocados from curious hobby groves in places like Montecito, Point Loma, Azusa, and Hollywood (yes, that Hollywood) to a global industry within which California actually now only plays a minor part. The book is only 175 pages long, and so it gives the reader only a teasing taste of some topics, but it does at least touch on all major developments.

Fun things I learned

I enjoy avocado history and have read some, but I still learned many things in California Avocados. A few of my favorites include the fact that George Washington ate avocados on a trip to Barbados in the Caribbean in 1751, which he wrote about in his diary, calling the fruit “avagado pair.” The name and spelling for the fruit in English wouldn’t be settled on for more than a century after Washington’s time.

Everyone in Southern California knows Camp Pendleton. It’s the only thing that prevents the coast from being completely paved between Imperial Beach and Santa Monica. But I did not know that Joseph Henry Pendleton, for whom the Marine Base is named, was also an “avocado hobbyist.”

Photographs

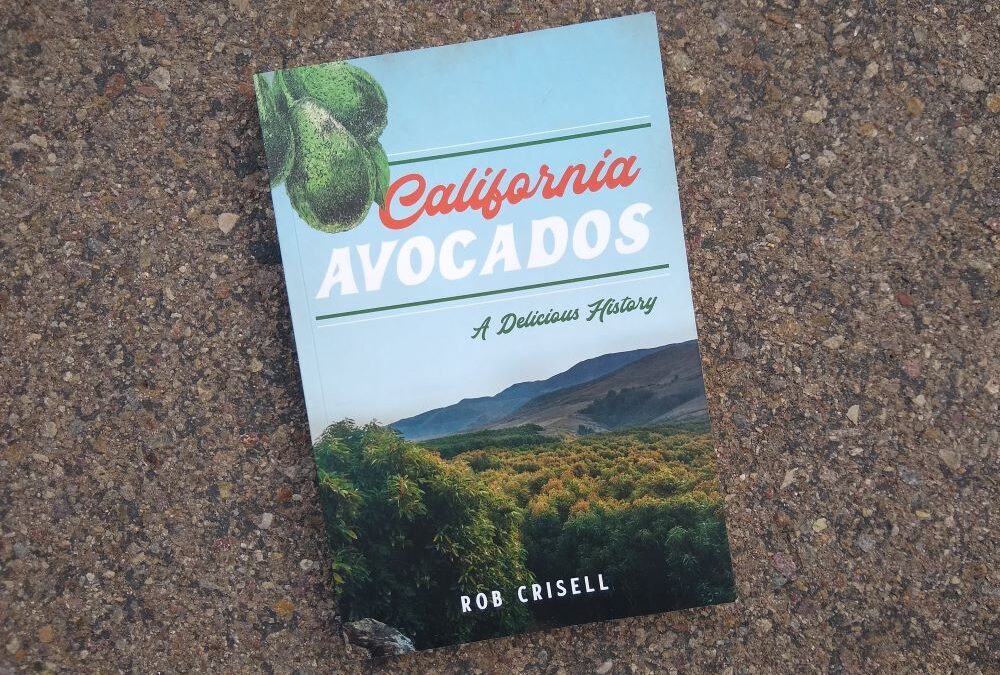

Crisell filled California Avocados with splendid photographs, some black and white, plus a healthy insert of 32 color images. The book is worth buying for the photos alone.

I found myself comparing some of the photos, particularly old and new. For example, on page 61 there is a photo of a magazine advertisement from 1930 showing avocados with large letters on them spelling the brand name CALAVO. Calavo is a portmanteau of California and avocado. It was at that time the main marketer of California avocados, and it aimed to distinguish itself from its main competitor: Florida.

Contrast this with the photo on page 129 of avocados for sale in a present-day Costco, where the boxes and the bagged fruit bear only the large letters of the generic “AVOCADOS.” One has to search for fine print to find the origin of the fruit. Why is the origin practically hidden these days?

The future of Avocado Land

I love how Crisell structured the book’s final chapter: “The Future of California Avocados.” It contains takes on topics from Water to Labor to San Diego County to Organic to Mexico to Varieties, given by a few dozen people with deep knowledge and experience in corners of the California Avocado world.

Ben Faber hits on the water topic, saying, “You’ve got to spend money to make money.” But Jaime Serrato notes that the cost of water has skyrocketed over the past few decades and that has put many growers out of business. As Charley Wolk puts it, “Water is about 90 percent of the cost of production of avocados [in San Diego County].”

Rob Brokaw gives great insight into the conundrum of avocado varieties and breeding today when he says, “Hass is so dominant that . . . what are you looking for? You’re looking for something that’s more Hass than Hass is.”

Most marketers of avocados have a strong preference for Hass, and they often present this preference as simply following customer demand. “Hass – that’s what the customer wants,” says Lee Cole of Calavo.

But Crisell shows in California Avocados that in the early days avocado eaters had to be coaxed into buying the warty, black-skinned Hass in the first place, for example with advertisements that called the variety “Black Gem Avocados.” They were “a diamond in the rough.” In other words (my words), “Yeah it’s ugly and looks rotten, but inside it’s pretty and tasty.” (See this ad from United Avocado Growers on page 100 of the book.)

Now, avocado breeders and growers are “hamstrung,” as Brokaw put it, because a new avocado that doesn’t look like Hass will require much marketing and patience, just as was required in the early days of Hass. Moreover, Hass has millions of dollars of promotion behind it from government in the form of the California Avocado Commission and especially the Hass Avocado Board.

Conclusion

Rob Crisell is the author of California Avocados, but in the writing he also had to play the role of mediator. Within the story of California Avocados, there are many players who are at times working together toward the same goal, at times competitors, and at times at variance with one another. Growers vs Marketers vs Handlers vs CAC/HAB vs North vs South vs Researchers.

Jan DeLyser, former marketer with the California Avocado Commission, alluded to this when she says on page 147: “But it’s never enough, at least from a grower standpoint. You have got to have respect for the growers–it’s their money–and I always felt like it was never enough.”

I think that Crisell pulled it off though. It probably helped that he is an outsider. A give-away is that from time to time in the book he calls varieties of avocados “varietals.” My guess is that this is a habit carried over from his experience in the world of wine grapes. (Crisell is author of the book “Temecula Valley Wineries.”) Avocado people don’t call them varietals. It’s a shibboleth that reveals that Crisell is from the outside looking in, which seemed to have helped him be able to let all parties speak. He told the story of California avocado development without shying away from sensitive topics and with including voices from all of the main players. That’s well done by the author.

In short, you can read this whole book and gain a sense of the history of avocados in California without knowing Crisell’s personal take on issues, other than that avocados are delicious and the people of California brought them to the world.

California Avocados: a Delicious History by Rob Crisell is published by Arcadia and can be purchased from Arcadia Publishing here and from Amazon here.

My avocado trees are raided by ground squirrels, so much waste! I’ve tried several things to stop this, but none has worked. Now that my Reed is beginning to produce, I need an answer. I plan on forming aluminum screen around a 5″ diameter removable tube, and enclose one end. The tube would be maybe 14″ long after the bottom was formed. I would split the screen at the top so it could reach over the limb carrying the stem, protecting the stem from squirrels, pinning the screen above that limb. I am 91, and got stopped on this project recently from a sciatica injury that keeps me from doing much until this pain is gone.

Could work. Or acquire a hand pumped BB gun and a taste for ground squirrel! It’s so frustrating to see avocados ruined after months of waiting.:( Good luck and get better!

I used a pellet gun, but sometimes it only wounded them, so I stopped. I built an owl nest box atop 15 feet of pipe, and am waiting for an owl to find it and enjoy the feast waiting here for it. Gophers and rats are also on the menu.

In Fallbrook, if the SantaAnna heat, tree rats, mice, opossum, and lack of bees, isn’t enough——tack on excessive water rates, makes trying to keep avocado growing from extinction.

Fertilizer prices may explode with the next tarriffs hitting imports next year. 🤨

Yeah, time to stock up on proper fertilizer before we can’t afford it.

Get a squirrelinator. The implication is that it’s a relocation trap but it comes packaged in this handy tray, which you have to deduce on your own to fill with water. The company seems to not want to offend some folks. Rats are a different story. We had a stray cat show up we’ve been feeding until we find its owner and have a feral kitten on the way after that.

Thanks, Bob. But I have one already. Unfortunately, it caught many other pests, including skunks, but no ground squirrels. Skunks became a bigger problem than I’d bargained for.

BTW, cats and small dogs don’t last long in our area. Coyotes have become a major problem in Yorba Linda.

Thank you for this thoughtful and thorough review, Greg. Really interesting!

And to David Williams: I hear you! I, too, have tried everything, including wrapping each fruit in multiple layers of thick nylon “socks” meant to protect apples from worms. The squirrels and/or rats eventually just eat right through. All that water and care…! I think that a serious cage might be the only way to go in our tightly planted suburban backyards. Feel better soon!

Cara in Pasadena

I have 9 young avocado trees, many varieties, each too large for any kind of a cage around them. I’ve had the Gwen a long time and it gives a sharecrop with the ground squirrels.

Rat terrier. That said, I have been having some luck using moth balls in their burrows. I throw a couple handfuls in the hole, shove in a Grey Pine cone (I am upstate, but in SoCal you could use Coulter Pine cones, and cover with dirt. They hate the smell. It doesn’t kill them, but makes them go elsewhere. The cone is gnarly and deters them from digging out.

Thank you from a local librarian for this great book review. Something I hope to add to our collection!

Hi Greg, and fellow gardeners! Any issues in avocados flowering in higher elevations. I am in Calimesa/yucaipa (2500ft) about 10 minutes from Redlands where avocados thrive but being in the foothills means there is some elevation difference. I’ve heard avos struggle to produce in my area. I have 2 trees – bacon and hass that have been in the ground for two years and neither have produced or flowered. Any tips?