I was speaking with an avocado farmer from South Africa, and he asked me about my favorite avocados to eat. That’s hard to answer, I started. But I told him that recently I’d had some Kahalu’u and Jan Boyce avocados that were very good. I turned it back to him, “What’s your favorite?”

“Fuerte.”

He’d answered almost before I’d finished the question.

And truthfully, even as I keep tasting new varieties of avocados that are interesting and delicious, the fruit from that tree that Carl Schmidt found in Atlixco, Mexico way back in 1911 remains my favorite too.

I’ll get to the growth habits and fruit production quirks of the Fuerte tree, and I’ll explore a bit about how the Fuerte came from Atlixco to Altadena to the world, so that you can decide if it is a good variety to plant in your yard. But first, let me please attempt to describe what I find wonderful about the fruit.

The Fuerte avocado

For an avocado, Fuerte is medium sized, averaging a little bigger than Hass fruit. The skin is green, only lightly bumpy with yellow dots, and it remains green even when it’s ripe. If the fruit has been mishandled, then black spots appear on the skin as it ripens (they are not hidden as they are with the black skin of Hass).

The shape is similar to a pear, but Fuerte avocados always have this unique slant to their bottom ends. I’ve always found this notable and it helps me to spot a Fuerte among a mix of avocado varieties.

Inside, the seed is pointy and a bit bigger than a typical Hass seed.

The adjective “nutty” is often used to describe the flavor of various avocados, but I think that it is most accurate for Fuerte. Is it hazelnut that the taste reminds me of? I can’t figure it out. But no other avocado has as distinctly a nutty flavor to me as Fuerte.

Fuerte’s texture is finer than Gwen, but not as smooth as Reed. It has the right amount of substance, especially when cut open at the right time. You don’t want to let a Fuerte get soft-ripe; they are best when firm-ripe.

I used to think that I was alone in still finding the Fuerte a notch tastier compared to all of the other excellent avocados available in the year 2020. Yet I continue to meet people like Jan, the farmer from South Africa, who have eaten many kinds of avocados and also still find the taste of Fuerte unsurpassed. Writes Gary Bender in Avocado Production in California, “The Fuerte is still thought by many in the avocado industry to be the best tasting.”

What’s the catch, then? Why can’t we find Fuerte avocados in the grocery store? Why doesn’t everyone have a Fuerte avocado tree growing in their yard?

Fuerte fruit production

My own Fuerte avocado tree illustrates the reason Fuerte avocados are rarely sold in grocery stores anymore, and why most Fuerte trees in backyards are not recently planted but rather leftovers from a past era.

My Fuerte is six years old, as is my older son. I planted it when he was born. Yet it still hasn’t given us much fruit. I’ve got other avocado trees in my yard that were planted at around the same time that have already provided us hundreds of avocados.

Is my Fuerte uniquely unproductive? No. “Individual [Fuerte] trees in a grove may produce good crops while many may produce little or nothing,” wrote Frank Koch in his 1983 publication, Avocado Grower’s Handbook. He adds, “It has been said that 80% of our Fuerte fruit comes from 20% of the trees.” And he concludes, “So when drone [Fuerte] trees are identified they should be grafted over.”

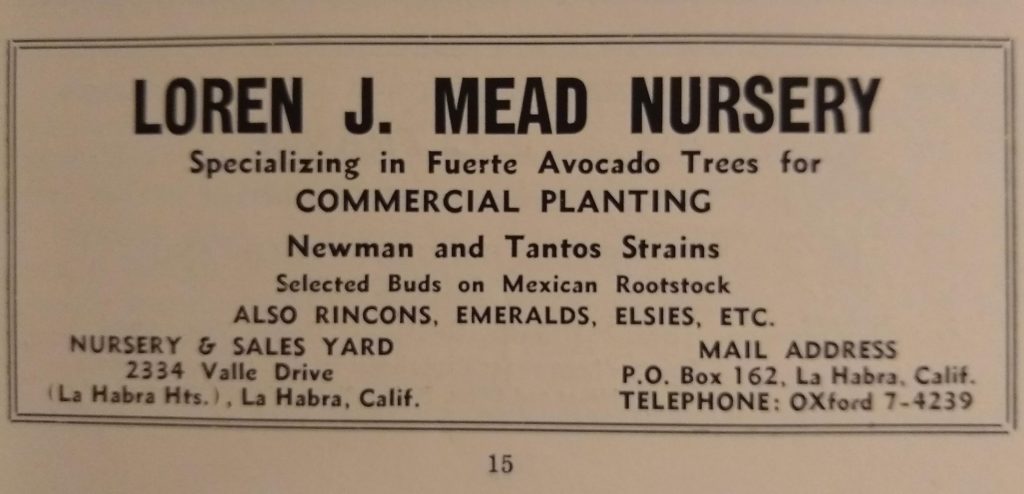

One of the first ideas for dealing with “drone” Fuertes was to graft them over using scion wood from the Fuerte trees that fruited well. It became accepted that over the years various strains of Fuerte had developed, and it was beneficial to make new trees from strains proven to produce. Here is an ad in the 1952 California Avocado Society Yearbook from a nursery marketing trees of specific Fuerte strains:

However, I’ve been collecting scion wood from well-producing Fuerte trees around Southern California for some years now and grafting them onto various trees in my own yard and elsewhere with mixed results thus far. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised. This approach was tried a long time ago here in California without much success.

Apparently, Fuerte has a penchant for mutating, or sporting, on branches or even individual buds. And it’s hard or even impossible to identify the mutations. (See comments from Bob Bergh about this here.)

Can girdling induce a non-bearing Fuerte tree to make fruit? Not in my experience. Girdling my Fuerte resulted in flowers but no fruit. And this aligns with what others have found. For example, in Israel, researchers reported that “sterile Fuerte trees have not been brought into production by girdling.”

Rootstocks for Fuerte

Another idea for why certain Fuerte trees produce well whereas others don’t relates to rootstocks. Maybe Fuerte trees bear better on certain rootstocks, and mine is not on the right one. They also found some success with this approach in Israel. Yet again, when tried in California it didn’t achieve consistent results.

Bear with me. I’m taking some time to explore the mysteries of the Fuerte’s erratic and unpredictable fruiting because it is a characteristic unique to Fuerte, and because you might also be dealing with a Fuerte tree in your yard that is unsatisfactory in how many avocados it gives you.

Fuerte temperature sensitivity

A final key factor that has been explored in the bearing of Fuerte trees relates to temperatures during flowering. It has been found that the fruit production of Fuerte trees is highly correlated with warm temperatures during bloom. More specifically, researchers observed that daily highs should be above about 70 and nightly lows should be above about 50 for good fruitset on Fuerte. And if the average is even higher, closer to 65, the better.

In 1934, some researchers purposely propagated some Fuerte trees with scion wood from low producing mother trees that were growing in a cool, foggy coastal location and planted the new trees in a warmer inland location . . . and the trees bore well! (See “Suggestive Evidence of the Existence of Strains in the Fuerte Avocado Variety.”)

Such findings have long caused the California Avocado Society to recommend that Fuerte be planted only away from the immediate coast, but not too far inland where nights are cold.

Where is my Fuerte tree? I’m twenty miles inland, but at an elevation of 1,400 feet in the foothills where nights are relatively cold, plus I planted my Fuerte immediately uphill of my garage where the cold air that slides down the hill each night gets stopped and pools. Not smart.

Last spring, I observed that my Fuerte rarely opened flowers in their female phase, which is the main problematic result of cool temperatures. Without female flowers there can be no pollination.

Fuerte variety development

Fuerte is the original avocado. Before Hass took over, Fuerte was the most widely planted variety.

It so happens that the town where I grew up has some of the oldest living Fuerte trees because it is not far from Altadena, where the first Fuertes were propagated back in 1911.

Fred Popenoe owned West India Gardens nursery in Altadena, and he hired Carl Schmidt to search for good avocados in Mexico. Schmidt took branches from the trees with the best fruit and shipped them up to California.

There in Altadena, all of Schmidt’s shipments were used to make grafted trees (clones), and Popenoe observed that the tree that Schmidt had labelled Number 15 grew exceptionally fast so he nicknamed it “Fuerte,” meaning strong in Spanish.

(There is an alternative story about how Fuerte got its name that is often repeated but which I believe is inaccurate. See my post about this: “How the Fuerte avocado really got its name.”)

(The tree that Schmidt had labelled Number 13 was later named Puebla. See my video profile of the Puebla avocado here.)

A man named J.T. Whedon of Yorba Linda was the first to plant a number of Fuerte avocado trees, purchased from Popenoe. After five years of growth, Whedon commented, “Of the twenty-one varieties planted in 1914, the Fuerte is the only one proving entirely satisfactory.”

Fuerte rapidly became the most desired avocado variety in California and then in other parts of the world — Spain, Australia, South Africa. More acres were planted to Fuerte than any other variety in California until about 1970.

When houses began to replace some of the early Fuerte groves in Southern California, not all trees were removed. Sometimes schools and housing developments left old avocado trees here and there. Here is one such old Fuerte in a friend’s backyard in my hometown.

Harvest season

Some Fuerte trees have a very long flowering season. Most avocado varieties do most of their flowering in March, April, and May. But I have seen Fuerte trees begin to bloom as early as October. Here is a Fuerte tree in San Clemente with flowers on October 3, 2019:

And here is a Fuerte tree in Poway approaching full bloom on January 18, 2020:

Yet, Fuerte trees will often still be blooming as late as June. All this adds up to a potentially long harvest season, both on individual trees as well as from Fuerte trees in Southern California as a whole.

Early set fruit might taste good starting in November. I think of Thanksgiving as the day to start testing avocados from Fuerte trees. And even in June there can be Fuertes that still taste good. But the heart of the normal Fuerte harvest season is approximately January into April for most of Southern California.

Is Fuerte a good avocado tree for your yard?

Despite the fact that Fuerte isn’t the most reliably productive avocado variety — which is one of the main reasons that Hass replaced it on commercial farms — it can still be worth planting in a backyard. One reason is that the fruit is so good to eat. Another is that it is a B-type avocado, which means that if you already have an A type (such as Hass), the Fuerte will likely improve the fruitfulness of that tree.

I grafted a couple of branches of an A-type variety called Pinkerton into my Fuerte, and the first time those little Pinkerton branches flowered they set more fruit than they could hold. That is the power of Fuerte pollen.

In addition, Fuerte is an attractive tree for an avocado. Its leaves are deep green and they get less leaf burn in the fall and winter compared to some other varieties. I also find the red flecks on the new shoots of a Fuerte tree to be attractive.

Fuerte is also slightly tougher than some varieties during winter cold snaps. Just a few weeks ago, my yard dropped to 25 degrees one night and my Fuerte came through in better shape than my Hass, Reed, Lamb, and some others.

If you only have a small space in your yard for an avocado tree, you might be better off with a naturally slower-growing variety, say Lamb or GEM — although it is possible to keep a Fuerte down to size with consistent pruning.

But maybe you have yard space and you want a real tree. I grew up climbing in the trees of the Fuerte orchard that surrounded a friend’s house. Another friend of mine grew up with a massive Fuerte shading her two-story house in Whittier. I know of many treehouses built in Fuertes. You won’t be building a treehouse in a wimpy Lamb or GEM.

My Fuerte may not be providing much fruit yet, but at least it is starting to shade the garage in the afternoon and can handle the kids climbing in it.

My suggestions for where to buy a Fuerte tree are HERE

My profiles of other avocado varieties are HERE

Find a list of all of my Yard Posts HERE

I’ve been eating Fuerte Avocados since November. As you stated, I started picking in November and have only a few left on the tree and it is Feb 21. The tree produced only a handful of fruit until I grafted Hass and Reed to an adjacent tree and onto a couple branches of the Fuerte tree. Even with a good Fuerte crop the Hass graft next to it amazes me every time I look at it due to the massive number of Hass avocados compared to the Fuerte. The Fuerte seed is twice the size of the Hass seed, but the largest seed I’ve seen was from the Mexicola Grande – it was almost 85% seed. I cut that tree to a stump and grafted Reed and Nabal to it. The other negative to the Fuerte are the strings – probably the part I like the least. They are least annoying if you cut across them, so they are short in length.

In my experience the Fuerte is very sensitive to the weather during fruit set as well has needing “A” type pollinators very close by. My 2 main reasons for growing Fuerte – good taste and having fruit from Nov until Hass are ready around March, but Hass are pretty good starting in Feb.

Thanks for the added info on Fuerte. When I got my hands on an Ettinger, Sharwil, and Carmen this Feb. I pulled out the little Fuertes I planted last fall. I don’t need a tree to climb, or landscape tree, just the fruits. Also have a Pinkerton, Bacon, and little Jim to take care of early fruit needs. Taste of Fuerte sounds great, but not so much the poor production and spreading habit.

What zip code do you live in? Is the Carmen available in San Diego? From what I’ve read the Carmen Hass flowers multiple times a year. I would like to get one of those or a cutting to graft. I’m in 92120. Also, where does an Ettinger come from and what are its qualities.

Hi Richard,

Subtropica Nursery in Fallbrook sells both Carmen and Ettinger: https://www.subtropicanurseries.com/

You’ll probably get Carmen’s “off” bloom in your location but the variety doesn’t have an off bloom in more inland locations (like mine). The off bloom usually happens around August, September, October; then the tree has a normal bloom in the late winter/early spring.

Ettinger comes from Israel. It is a green skin, roughly the same size as Fuerte, but a lighter green color. Seed is fairly big. Flavor is good, but not as good as Fuerte (to me). Texture is smooth and pleasing. Harvest season is basically winter.

Hey Greg. I’m pretty sure I have a “drone” Fuerte–it’s over 8 years old and has never flowered or fruited. I am thinking of shovel-pruning it–I don’t have the wherewithal to do any grafting. What variety would complement my 4-year-old 7′ tall Pinkerton? It’s already producing fruit–maybe 6 per year, so not many, but they are quite large and delicious!

Hi MT,

Bummer about the drone Fuerte. To complement Pinkerton, you might plant a B type. I have seen that Pinkertons produce much better with a B type nearby although they produce some without. The problem is that I don’t know of a B type to recommend that has a harvest season that is much different from Pinkerton. So if you’re only going to have one additional tree besides your Pinkerton, I would go with Lamb or Reed since they will give you an extended avocado harvest and they’ll likely help somewhat with Pinkerton pollination too.

Greg, you may have read this on the boron deficiency on Fuerte trees pollination. I just bought 4 Small Fuerte’s to add to my collection, I live on Kauai with 16 varieties of avos and other citrus, mango, etc… Keep up the good work, I learn a lot from your Posts, Aloha Ward

https://www.avocadosource.com/WAC1/WAC1_p043.pdf

I am in sunny so cal & my fuertes are dropping fruit in July & August. I water every 2-3 days depending on how hot outside & how dry the soil. Is this normal? They soften after 2 days but the inside is not very soft or tasty.

Hello Terri,

My Fuerte tree flowers around February March. The fruit gets fairly large by November and picking late November the fruit is good but a little young. December is the prime time to pick and it will usually stay on the tree until February. The mature fruit will drop if the tree is stressed in any way whether it’s underwatering or over watering or excessive heat and dryness or the opposite weather. If you had no mature fruit in March 2024 and your tree flowered and you have baby fruit and that baby fruit is what is dropping in August then you have to look at how much fruit is on the tree to begin with. If your tree is loaded with fruit this year then it’s normal for it to drop some of that fruit. Somehow the tree knows if it’s got enough nutrients in the soil and enough water and enough sunlight to support a very large crop and if it doesn’t it will drop what it can’t support.

hi Teri

I am an old guy living in Temecula for past 40 years. First 15 years I killed many new Avocado trees bought from big box stores. I finally realized that our local winter climate is often a young tree killer. I build temporary ‘housing’ to protect the new trees planted, even providing an electrical heater at the base of the trees, for those sub-freezing nites.

I have read volumes of articles, postings etc. regarding backyard avocado tree growing.

I have 6 excellent trees growing and producing these past 10 years. Mostly 15 gallon trees bought from the various tree farms of North County San Diego regions.

I find that all the talk and suggestions you find in literature and postings are at best, simply a guide.

All my trees (Fuertes, Lamb, Stewart, GEM, Reed, and Sir Prize) exhibit habits of flowering and fruiting that are often very different from what ‘other folks’ report from their experiences.

Some very helpful tips are often suggested by many. Avocado Trees are intriguing and frustrating. Even your tree will respond differently from year to year with respect to flowering and it fruiting. I love my trees, but they drive my nuts. We each have to enjoy attempting to provide/manipulate ‘our’ tree’s environments as best we can. My various citrus and pomegranate trees are relatively care-free when compared to Avocado trees.

I have found that, protecting young trees from cold snaps is critical to get the tree past the first couple of years in the ground. Most need good drainage. Most often the trees need enough water but not too dang much. Trimming your trees tends to produce more lateral branches thus increase flowering / fruit. Some type of mulch around the base or under the canopy of the trees is beneficial.

It is an adventure, but you have to enjoy trying to figure out what ‘you’re tree(s) need from you. Wow! huh??but that is the fun and sometimes even the reward!

I appreciate following Greg on YouTube and his Yard Posts…..BUT his personal experiences are often very different than my personal experiences (and he is only about 50 miles away from my location).

Avocado trees are very sensitive to each our own very unique micro environments. Our job and joy/frustration is to attempt to maximize our trees health, thus fruit production. There is no magic bullet that works for every backyard grower.

Many people I know think how ‘lucky’ I am to have the productive avocado trees that I have. My father, died last year (in his late 90’s) and used to smile and ask me how much each of my avocados cost me? with a twinkle in his eye, he would suggest $25 a piece! my reply, with a big grin, I would say “it is not about the cost to me dad”! Dad enjoyed the boxes of fruit I would send to him.

My Fuertes produces a few hundred fruit ‘nearly’ every year. some years fruit is small, some years the fruit is large. My Fuertes fruit is never ready to pick until March or April at the earliest. Go figure! no worries I just enjoy my harvest when they come to me, regardless of what other people report as ‘harvest times’.

I used to throw lavender branches into my flowering avocado trees, or spray honey water on my trees as they flowered. My bees seemed to love my citrus flowers much more than the ugly avo flowers. But I find that flies and even ants/bugs do some pollinating for the avo flowers. I have a bee hive and that helps greatly…but that is another intense activity with struggles of it’s own.

How do the trees ‘know to drop baby fruit in anticipation of the stresses of to many babies on the tree? hum?

When I returned from service in Vietnam, going to college in San Diego, I was a hippy-veteran-farmer in our first house in La Mesa, CA. I had 1/2 acre of vegetable garden with some fruit trees. People would stop by and ask and wonder how I had such a big productive garden. The answer is with love and much hard work, sweat….that’s how. You have to love the work, the adventure and the wonder of seeds to plants to fruit. I grow around 120 heirloom tomato plants each year (seeds to plant to garden beds and to harvest) but each year is a little different from the previous…interesting!

Most folks on these forum have the Love, which is the root of the endeavor. I don’t have many answers to many questions, except…..keep at it and enjoy the learning experience your plants and environment teaches you along the way. Gardening is a Wonder!

dropped Fuertes avocados? I find that mine are picked not dropped. hum? I don’t let mature fruit ‘drop’…for me, that is way to late or too dang early… ;neither situation provides me good fruit.

best regards,

still practicing for all these past 76 years!

Hi Gary,

I appreciate your attitude. I think it’s a mature one that comes from experience. And wouldn’t it be boring if there were a formula to follow for growing food? I like that every year is different, and even my neighbor’s yard is different; there’s no end to the learning and experimentation.

Hi Richard,

Thanks for mentioning both the strings and the need for a pollenizer. I have yet to figure out why some Fuerte fruit (and other varieties) has strings whereas others don’t. I notice it more on certain trees, from early picked fruit, from fertilized trees, and from younger trees. But these observations haven’t been perfectly consistent.

Fuerte has been found to benefit from an A-type pollenizer, such as Hass, in many studies. But I didn’t mention it above because I’ve also seen many lone Fuerte trees that produce well. More important than a pollenizer seems to be the right temperatures and high bee activity.

Several years ago I bought some avocados from Costco imported from Chile. They had stings so thick and tough I returned them. I think the strings are veins and their size is genetic. It seems that the strings in Fuerte are thicker in the larger avocados. Also, at the end of the season for Fuerte the strings can get black especially where they converge at the bottom of the avocado. I had rats eating my Tahoe Gold and Pixie Tangerines, so I picked them all. Now I have rats eating my Hass. They chew the stems until they drop and then devour them on the ground. If you have a rat solution I would really like to know what it is. Bait does not work since they love the fruit more.

Hi Richard,

I think you’re right about the strings. And it’s one of the few flaws of Fuerte avocados, that they sometimes have strings.

I wish I could help with the rats, but I actually have almost no experience dealing with them. The only thing I can say is that we lost our cat some months ago, and since then I’ve seen the first mouse and the first rat in our yard. The cat was outdoors at all times, and I assume it was a factor in the prior absence of these pests. We’re going to get another outdoor cat soon.

We have a cat, but it is indoors only. I wanted to get a couple feral cats for outside, but the woman of the house would bring them in. I don’t want that. Our cat sits at the door all day watching the lizards and other critters with extreme focus. I wish I could let him do what they live for. I agree with you that cats would be the best solution. I just need a solution for my sweetheart to not rescue them from the back yard.

I have Hass & fuerte planted together. Neighbor also has avocado tree. So rats is the problem too. I heard about feeding them bubble gum, and we did, & other way of getting rid of them. The best is the Tom cat rat trap. It is black and snap hard, so rats die quickly. More humane. The week we put Tom cat I got 2 rats. We have 6 Tom cat

rat trap. Be careful if you have pets. It’s very powerful. But so far it is the best.

Janet, thanks for the suggestions. I’ve been using the Tomcat traps for years. They are the best snap traps. The rats go into the trees and eat out the fruit leaving a shell hanging on the tree – oranges, pomegranates, cherimoia, etc. I even tried putting the rat traps in the trees next to the fruit, but the rats are to smart to fall for it. I even tried putting the green block poison in a half eaten orange still in the tree. I put a trail camera on it and watched the rat push the poison bait out of the orange and eat the orange. I finally talked the wife into getting 2 outdoor feral cats to save them from being put to sleep. We caged them for 4 weeks as instructed. We let them out a week ago. 1 cat stayed for one night and is gone somewhere. The other cat is hanging around the house. I have not seen any more tomatoes being eaten. I’m thinking that maybe the cat is marking her territory. So far so good. The test will be the ripe oranges and the Tahoe gold mandarins when that occurs. I guess like people, some cats are homebodies and some are nomads. The cat that left was going crazy for Costco rotisserie chicken that we gave her everyday, so it was a surprise that she left. We have security cameras, so I know she was not attacked on my property. Greg was right about his cat keeping the rats away – natural is best!

Not sure whereabouts you are based. Cats are a serious problem here in Australia. Killing untold native wildlife indiscriminately. We find a better solution is snakes – pythons are the best as they are non venomous. What are the natural predators of rats where you are?

Two cats are an unbeatable solution for rats in an Avocado tree. last February, I noticed my female cat way up in the Fuerte tree early one evening, slowly creeping way out on a branch ( I did not see the rat she was stalking. All of a sudden, the rat jumped out of the tree and my black male came out of nowhere, caught it and ran off with it before it even hit the ground. From time to time, I have found dead rats on my doorstep (including this one about an hour later), but this was the only time I had witnessed their hunting technique. Rarely do I find an Avocado with a bite mark. Before I got those cats, rats would take a bite or two from dozens of Avocados in that tree..

Great story! I’ll be getting a second and maybe a third cat in a couple months. The outdoor cat we have now roams around the yard, but does not seem to be the vicious hunter I was hoping for. About 5 years ago the neighbors cat left me a rats ass and a bird head as gifts. I was impressed and are the type gifts I long for now. Too bad that cat died of old age – 18 years old. I wish I could be more selective, but there is a shortage of barn cats in San Diego. I had to put cages on my figs just to get a few and now my Cherimoya’s will need to be caged or they will get wiped out. If you ever need a home for your cats, you know who to contact!

Shoot them with a BB or pellet gun.

Look into working cats. There are organizations and some animal shelters that adopt out working cats that are feral and not likely to be adopted as a family cat but do a great job keeping the rodents down. I was overrun with rats in all my fruit trees and had very limited success in trapping them. At one time they were nesting in my attic. Since I adopted my working cats, I rarely see rats. The effect was dramatic.

The organization I adopted from is the Kitty Bungalow Charm School for Wayward Cats. It is a non profit organization in Los Angeles.

https://www.kittybungalow.org/

There is great information on their website and they help you set up for success and help you “install your cats” I can’t say enough good things about their program and my cats! Good luck!

https://www.kittybungalow.org/

Thank you Cindy.

A few years ago I got a couple cats and a cage and followed all the rules to acclimate them and one ran away but was very friendly so I think somebody grabbed it in a neighborhood and the other one stayed and the wife fed the cat and love the cat stayed outside for I guess a couple years and then it got cancer according to the vet and it was never killing any rats and then it died and the wife was devastated. So she doesn’t want me to get anymore but I’ll check this organization and if they’re real feral cats and rat killers then I’ll be happy to give them a home here. Thanks again.

Hi Richard,

My in-laws have a Doberman that is good a killing/ “Treeing” rats. If the dog can’t catch the rat it will bark and circle the tree or bush that it is hiding in. Our go to for the treed rats is a BB gun.

Thanks for the info, Greg! Do you have any experience with “Sir Prize”? It is a type B, similar to Hass, and by all accounts its fruiting season is October-January. Fruiting season for “Pinkerton” (where I am in SoCal) is spring, so I was thinking “Sir Prize” might be a good companion avocado.

Hi MT,

I do have experience with Sir-Prize. It is a B type, but I’ve never heard of its fruit maturing as early as October. To me, it has never tasted very good until about February. But it does taste very good.

Okay, Greg, with my drone Fuerte, I think I’ve decided that the best option for me at this point if to hire someone to graft a well-producing Fuerte onto the drone tree. It’s a drone but so healthy and lush, it seems a shame to throw it away.

Otherwise, as a replacement, neither Reed or Lamb are pollenators for the Pinkerton. As far as B-types, I’m not a fan of Bacon or Zutano. I scoured your site and it looks like Sir Prize is not great as far as taste, either. Sharwill (for taste and tree) might work.

Do you agree with the grafting option? If so, can you recommend someone in LA County?

Hi MT,

The grafting option is a possibility. I’m doing that with my drone Fuerte right now.

But since the tree has never even flowered, I would be suspicious of the rootstock too, not just the Fuerte scion. Shovel-pruning it might be smarter.

I don’t know anyone personally in L.A. County whom I can recommend for grafting, but you could contact the local chapter of the California Rare Fruit Growers to try to find someone. There are a couple chapters in different parts of L.A. County.

Hi Greg. Sorry to hear that your fuerte isn’t working out. Do you think it’s because your climate or just a bad tree? I worry about this because I’m in a similar climate and I really would like my fuerte to be fruitful someday. Thanks again

I bought my Fuerte and a Hass about 15 years ago for my Redlands yard. The Haas never grew, but the Fuerte grew and produced avocados in its 3rd year. By year 7 it was producing 300-350 fruits each year. By year nine it was approaching 35 feet tall and producing 400+ fruits ranging from 14 ozs to 21 ozs. I’ve topped it three times, the last being from 40 feet back down to 30’ and still get 400 to 450 of the most delicious, buttery, avocados. Oddly, in comparing notes with others my Fuerte seeds are smaller than the haas with a bigger fruit. I assumed they were not commercially grown because of their delicate thin skin, which would make transporting them very difficult. My picking season is from late November through March, and then the new (3 years old) Haas takes over through June.

Hi Jesse,

Thanks for sharing this about your Fuerte. Sounds like you’ve got a winning strain of Fuerte. I’ve never known a Fuerte to have a smaller seed on average compared to Hass.

Sounds like you’ve got a winning climate in your yard as well. A few years ago, I took scion wood from an old Fuerte tree in Redlands that was extremely and consistently productive like yours. It’s now grafted and growing in my yard. Maybe I could get a stick from your Fuerte someday to test it out, too?

The commercial disadvantage of Fuerte is its thin skin, but it’s also the fact that it doesn’t turn black when it’s ripe. Because of this, if there are bruises on a Fuerte they show as the fruit ripens whereas on a black-skinned avocado like Hass the bruises just blend in and hide — until you cut it open.

You’re absolutely right that to sell green-skinned avocados pickers and handlers have to be more careful and slower or else consumers won’t buy the fruit because they can see the damage.

I would be happy to share my tree with you. It’s now approaching 35 feet again and it’s probably close to 20 feet across at the base. We have lots of friends who begin begging for our fruits just after the first of the year.

I’ve noticed that sometimes my Hass are more rounded and have a larger seed than when they are more slender. I assume it is from the variety that pollinates the flower. My Fuerte are very consistent and their seeds have always been large for the size of the fruit. Maybe what you think is Hass is something else or maybe it was pollinated by other trees in the neighborhood, like from a Mexicola Grande – the largest seed I’ve seen so far. I agree that the Hass thick skin enables the handlers to toss them around. I like the thin skin of the Fuerte because it is easy to tell when it is ready by pushing on the top part. Thanks for sharing your experience.

I’ve been searching for a good source for a few Fuerte scions to graft onto a 3 year old tree grown from seed. Any chance you would make a few available from your Fuerte that seems to produces so beautifully?? I am in Westlake Village but willing to drive or whatever. thanks steve

Hi Steve,

Jesse emailed me to say that he has moved but the new owners of the tree would likely let you have scions. If you want to drive out to Redlands for that, let me know and I’ll get you the contact information.

But there are certainly many good Fuertes closer to you in Westlake Village. I know of some old Fuertes in Simi Valley, for example. There’s likely a grove in Moorpark that has some Fuertes that produce well. I would either drive around with eyes open for Fuerte trees or get in touch with a chapter of the California Rare Fruit Growers, which has a scion exchange each winter. Someone there can certainly connect you to a good source of Fuerte scions.

Thanks for the response, Greg. I’ll look around in Simi–any slightly more exact areas (Simi Valley is a pretty big place :-)) Thanks again.

If

If Steve Krieger is still looking for Fuerte scions in Simi Valley please give him my email address.

Thanx … Ken

steve Kriegers

Based on your advice, I picked one very large avocado from the 40+ year old tree I inherited when buying my house. Picked it on Thanksgiving. It’s Dec 8th now. It just got soft enough to eat and OMG-it’s creamy and yummy. I was pretty stressed out about the fruit drop we saw with the warm weather and fires. There is an amazing amount of fruit on the tree and I am wondering if they will hold out over the next couple of months. I am not really sure how to care for this tree. Is it ok to leave them on the tree over the next couple of months or should I harvest them soon?

Great to hear, Linda! I also picked my first Fuerte on Thanksgiving and ate it yesterday. Same thing: creamy and yummy. Fuerte is so delicious!

Fuerte has good hang time. The avocados will be fine hanging on the tree for you for many months, at least into April, possibly into June. Just pick as many as you want to eat, as you want to eat them. Don’t think you need to pick them soon or else they’ll drop off. A few will drop here and there, especially in strong winds, but don’t let that scare you.

I have one of the old growth fuerte trees in my yard. My house was built 1920 in Monrovia so I assume it was planted sometime that decade. It’s about 40 feet tall and produces hundreds of fruit every year, especially if we pick most of the tree by February when it starts to bloom again. The first branches sprout from the trunk at about 7 ft high, but the shoots hang down low, nearly to the ground unless pruned.

We are about to start a house addition that will require cutting back part of the south facing branches (especially the low hanging ones) and we were thinking of laying gravel and patio stones under the tree which is currently just bare dirt. Do you think covering the dirt will jeopardize the tree or fruit production? Some of the roots stick out above the soil.

Hi Brandon,

I’d be concerned about two things: One, branches on the south side perform the important function of protecting the trunk and other branches from the strongest sun. Cut back only as many as necessary, and protect exposed trunk and branches with white latex paint or another sunscreen.

Two, cover the dirt only as much as necessary. The covering might compact the dirt below to a degree and it might also reduce the air and water penetration too. If you’re just doing it under part of the canopy, then that’s less risky than under the whole canopy.

I have a Haase and a Fuerte. They are both grafted. I ordered them from a nursery in Covina about 20 years ago. They produced about 3 years after planting. Every year they produce over 200 avocados. They Haas more then the Fuerte but they both do very well. It is now June and we still have avocados to pick. The Fuerte is starting to produce baby avocados. Should I pick the remaining avocados before the new ones grow? We live in Covina

Hi Chuck,

That’s a nice pair of trees you have. I grew up next door to you in Glendora. I find that in most years Fuertes should be picked by June. About now they start to get some hard spots as they ripen and unappealing grayish color in the flesh near the seed. So yeah, I would harvest the rest of your Fuertes pretty soon. But don’t worry about their effect on the new crop. I imagine there aren’t too many left at this point to harm the development of those.

My tree is 50 years old Fuentes and I find if I scare the trunk I get double the avocados the following year why is that

Hi Jon,

Girdling or ringing an avocado tree has been done for a long time, usually getting the results you get. The idea is that the sap flow is interrupted and energy is kept up high in the branch that is girdled, causing that branch to bloom profusely.

July 1, 2021 and we picked 10 from our Fuerte in Fullerton, CA. The tree was planted in 1971 and came from Walmart. I left a shoot from the root stock which produces 1-2 pound avocados of unknown variety. Same bloom cycle as the fuerte but bigger and smoother. Very tall tree, twice as tall as the Fuerte with no pruning.

Hi Richard,

Am I reading that right? You bought your Fuerte tree from Walmart back in 1971?

I’m pretty sure it was Walmart but It could have been some other discount store. I’m an old fart and my memory isn’t great. My wife says it was more like late 70’s and she doesn’t think Walmart was in California back then. I remember it was in Anaheim and it wasn’t a nursery. I think she’s probably right on the date since it was after we built our koi pond which was 78. Sorry for getting it wrong. I had the tree for a long time and wasn’t getting many avocados. I asked a friend who had a grove in Fallbrook and he asked if I was fertilizing the tree. Of course I wasn’t. I found out they do a lot better if you feed them.

Hi Greg, I have an older fairly large size Fuerte tree In the yard of my new house in Rancho Bernardo. Last year the fruit were large and delicious. This year it has produced hundreds of fruit. I was thinking of having it trimmed or having a branch or two cut since the weight is not evenly distributed. I was advised to wait until late winter or early spring. Yesterday one of the highest branches snapped – maybe from the weight of the fruit? There were a couple hundred avocados just on this branch. What would you recommend I do to the branch where it was snapped off? Should I make a clean cut? Should I treat it with something? Any recommendations would be appreciated.

Hi Roxy,

It’s usually best to clean up a break like yours. A smooth cut made just above the branch collar is more likely to heal well. The collar is the slightly swollen area where the branch emerges from the larger branch or trunk below it. No need to treat it with anything. You can do this now.

I have exported fuerte 1 container 40 ft by sea and now is almost 38 days it has arrived to port of destination in refer container with atmosphere control please could tel me will it arrive safe as i see the time is alot almost 1 month and 8 days

i am moving from the santa clara, san jose area.

i am taking along 8 7- 9 year old fuerte saplings.

3 are just getting their first buds for fruit.

the tree that is the parent is about 80 years old and still produces hundreds of avocados each year.

the thing is this trees fruit is the size of a large mango or a papaya. they are at least three times or more the size of the hass.

i have heard the hass was developed from the fuerte by accident, but was nurtured and marketed because it grew faster than the fuerte? although my 80 plus year old tree produces fuit 2 times a year! furte always!

We have 2 Fuertes trees that were planted in the mid 50’s. They are producing well (usually a heavier crop every other year) and we enjoy them very much. We live in the Central Valley of CA, Tulare.

I thought this was going to be a big year for my fuerte! I live on a hill just south of Ramona so I normally don’t get the weather extremes the valley gets…but, this past year I saw temperatures from 19 to 119..and the Santa Ana’s decided I needed one less branch on my tree.The hundreds of pea size avocados I started with ended up being 2 avocados at harvest time! They are 2 beautiful avocados, but it makes me dream about what could of been! The heart break of Fuerte!

Breaks my heart just to read that.

Greg, I wrote to you about my avocado trees, being a rookie who had never been successful as a home grower. We have a relatively small yard in Pt Loma. 6 years ago we planted a Hass and a Fuerte tree, both about 7’ tall. They took off immediately and have been extremely prolific. The Fuerte has possibly 100 on it now, the Hass close to the same. A year after planting those 2 I found a potted knee high Nabal. It took a year for it to really get started going waist high then took off. Last year we harvested 22 softball size fruits and currently has 14 that are approaching tennis ball size. The trees, all 3 are at least 15’ tall and spreading out. I’m not sure how much to prune but surely need to as the yard is small. Winter fertilizer? Also the Hass has presea (sp) mite all over it. How do you treat the leaves? If ever around PT Loma you’re more than welcome to take cuttings from the Fuerte or the other 2 if you can use them. Sorry for the essay, I’m getting too verbose.

Hi Denny,

Great to hear your trees are doing so well. I was in Point Loma a couple days ago helping a friend get ready to plant some avocados in his yard there. He’ll be encouraged to hear how well your trees are fruiting.

Winter fertilizer? If you use organic materials like compost or wood chips, then apply them anytime. If you use fertilizers though, I’d pause about now and wait until spring when the roots begin to grow again and the tree can take it up.

Persea mite? I’d only worry about it if the infection is so bad that leaves are falling. They’re done doing their damage at this point this year. I personally only know one non-commercial farmer who does anything for persea mites, and he just releases predator mites at certain times. If you think your infection is really bad, let me know and I’ll guide you further.

Mine did the same! So many sweet little pea sized babies and within a few weeks all were dropped except a couple. Definitely heartbreaking!

I’m a lot happier this year, I’ve got at least 25 avocados that have made it to 2″. Its still hard to see the pea size ones on the ground in the spring!

Great news, Scott! If that young fruit makes it into August, it is very unlikely to drop. Seems you’re likely to get a few dozen mature Fuertes this winter. (No crazy late summer heat waves, please.)

That’s is great news! I’m still having nightmares from the 117′ july!

this happened to us one year due to heat stress. I think the squirrels were hopeful to get some moisture out of them during the heat wave too. Since then, we water nearly every day during the heat waves above 100 and it fared much better. Also, pick all the fruit off the tree from the previous year before it gets to full bloom in late winter. The tree will have more water/energy for the new buds.

Thanks for the thorough Fuerte profile- it’s really informative! Mine was planted last July and am still waiting for the first set of flowers. It’s the only Avocado tree I have, but am hopeful since I’m in East LA where I’m surrounded by many A-type pollenizer trees(next door neighbor has a massive 40 ft tree that makes very dark looking fruit and is in full flowering mode). Also, the lowest yearly temps are usually in the upper 30’s. If anything it’s the summer heat that my Fuerte has shown not to be fond of. Are Fuerte’s more sensitive to hear than other varieties? See there’s some discussion about grafting a type A- how old does the Fuerte need to be to graft a Haas or other type A onto a branch?

You need to get the scion (branch to be grafted) from a producing tree, such as a Hass. The age of your Fuerte tree does not matter. A pencil diameter is the preferred size, but I’ve grafted 1/8″ diameter and larger and have been successful. Search youtube for Dan Willley – he has some great grafting videos.

Hi Paul,

I haven’t found Fuerte to be extra sensitive to summer heat. Here’s a video of some varieties in my yard, including Fuerte, after the July 2018 record heat: https://youtu.be/Umm_WOoGERo

You can graft an A-type branch onto your Fuerte now. It’s big enough.

Thanks for sharing that video. Hopefully we won’t see the record heat of 2018 this summer, but maybe it’s wise to paint some of the exposed branches on the side that gets mid afternoon sun. If I were to do that, what month is best to do that?

Hi Paul,

Yes, that’s a good idea. You can paint now. Just be sure to have it done by the end of May.

Hi Greg,

With the weird weather we’ve had this spring my Fuerte seems to have developed a new issue I’m not sure is related to overwatering or mites. It started getting unusually hot at the end of April so I increased watering as it was leafing out. However, I’m noticing on many new leaves and some slightly older leaves these spots.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/18YRsRbFjSkaOTDKMI58OEPRmqE98h_KR/view?usp=sharing

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1drqQCu-ImroVuAvxKfJMRaWEzR4HiJas/view?usp=sharing

Any ideas what this is?

Thanks!

Hi Paul,

My guess is persea mites. Check out this page: https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/avocado/persea-mite/

Greg, I have an 8 yr. old Fuerte tree in my yard that has a couple of dozen avocados every other year, but a neighbor has a Fuerte that is probably 20-25 years old and produces hundreds of fruit every year….can I graft a piece of the prolific tree onto my tree and if so, when? I live south of you in the Spring Valley area. Also need to know when and how much to prune from this tree. Thanks for any help

Hi Karen,

Yes, you can. There’s no guarantee, however, that the graft will produce as well on your tree because it’s possible that an inhibiting factor is your rootstock. But you’ll never know unless you try.

When to try? Technically, you can graft any day of the year with some success, but it is easiest in late winter and very early spring. March is usually the best month, in general.

Thanks! I think I’ll give it a shot next March to see what happens. Right now this tree itself, has grown leaps and bounds this past year, so I’m assuming that most of it’s energy is being put into the new growth. It has tripled in size.

I’ve been waiting for avocados to come up in the conversation. Earl, from “Earls Organic” in San Francisco, and I favor Fuerte over the rest. We’ve been enjoying them since the 70’s, at my fruit truck next to Golden Gate Park in SF.

I’m looking for a 100 varieties that we’re planting next year in Hawaii. I already have over 100 varieties that I have sourced. California Dept of Agriculture and Human Resources tested some 100 in 2004, listed on the internet.

I’ve tried connecting with Julie Frink, but to no avail.

HELP!

Michael, 808-597-4717, “bakerdudesland@gmail.com”

Hi,

I’ve been reading Yard Posts since right before I bought my first avocado – a Reed – in 2017. This summer should be its first crop!

Any thoughts on how much (salty San Diego) water an avocado on Zutano rootstock needs to thrive vs the same tree on Dusa (salt resistant) rootstock? I am thinking of getting either a Fuerte or Sir Prize soon, and the idea of not having to leach so copiously is attractive. This tree will be going in the front yard, so it would be nice if it could stay presentable most of the year. 15 gal. of either are available on Zutano, or I could get a much smaller tree on Dusa from Subtropica. Is it worth the wait to start with the spiffy rootstock?

My Reed seems to be much happier since I started supplementing its normal watering with stored rainwater. Last summer I started pouring 10 gallons of rainwater around it a few times a month as a chaser right after the sprinklers finished up. I only have a few rainbarrels, so I thought the most efficient way to use rainwater would be to flush the salts out of the mulch and top few inches of soil. That way salts wouldn’t get concentrated due to evaporation in the mulch.

Hi Mike,

I like your thoughts here. My experience with Fuerte and Sir-Prize, in my yard and elsewhere, has Fuerte as somewhat more drought and salt tolerant, as shown by less leaf burn in the fall and winter.

I had a Sir-Prize on seedling Zutano rootstock that I actually cut down because it got such terrible leaf burn every year that I couldn’t stand looking at it anymore, but I’ve seen other Sir-Prize trees on seedling Zutano rootstocks that weren’t as sensitive. That’s the way seedling rootstocks go: they’re variable.

Using a salt tolerant rootstock like Dusa instead of seedling Zutano would probably help, and instead of Dusa you might want to go with one of the the other clonal rootstocks at Subtropica that are simply labeled “S/T” or “Salt Tolerant”; I planted a Fuerte on one of those at a friend’s place and it is doing well.

That being said, if you are in a hurry, you could probably grow a nice looking and productive Fuerte or Sir-Prize on seedling Zutano roots. I’ve seen some such trees in other yards although I can’t say exactly how much they’re being watered. My own Fuerte on seedling Zutano rootstock gets little leaf burn, and it’s actually in a part of my yard where I can’t get extra rainwater to it.

Bottom line: seedling Zutano rootstock is somewhat variable; clonal rootstocks are consistent. For the surest bet at the least leaf burn, go with Fuerte on salt-tolerant clonal roots.

Interesting topic Greg and mike. I just wanted to be sure after reading this. Is the leaf burn mainly cosmetic? I have a Fuerte on unknown rootstock that looks terrible right now and I’m anxiously waiting for spring flushes to bring out fresh leaves and hopefully flowers. I also have a Hass on unknown rootstock that looks pretty good in comparison. My reed on g6 rootstock has a tiny amount of cold damage but otherwise seems to love my salty water. I just hope the burned up ugly leaves on that Fuerte doesn’t stop potential fruit production.

My understanding is that if a lot of leaves are significantly burned, the tree has to expend energy on replacing them that otherwise would have gone to flowering and fruiting.

Hi Walter and Mike,

My understanding is the same as Mike’s. I’ve heard smart people say that if about 20 percent or less of the tree’s leaves are burned then fruit production isn’t affected.

But! I’ve also seen some avocado trees with more than 20 percent of the canopy burned yet still set and hold lots of fruit the next year.

Hi Greg, what an amazing blog! You are my hero! So lucky to find this. I have a young family on an acre in Escondido near San Pasqual Valley and we have put in lots of fruit trees over the past couple of years. Just starting with avocados. Wanted to to run it by you and see if I did it right: we are going with the trifecta of Reed, Hass, Fuerte. Because of space, I am planting them 8 feet apart on a slight southwest facing slope, right above a natural swale. I want to also use them as a privacy screen at the front of our property, so keeping them close is good, and will prune them to stay compact. Is that too close for Fuerte? We also have very poor clay silt with K deficiencies. I will be following your watering schedule and staking guidelines. Any tips?! Thanks again for all these resources!

Hi Ben,

Thanks so much for the kind words! We have a lot in common. I like everything you’re planning there. You might want to stick the Reed in the middle because Reed usually naturally grows more upright than Hass or Fuerte. (I’m assuming that the trees on each end will be able to spread just a bit more than the one in the middle.) Let me know how things go.

Hi Richard, glad I found your web site. I live in Escondido, not far from you. I have 4 Hass, one Pinkerton, one Fuerte, and my favorite, a Nabal. I can’t find much on cultural parctices to maximize production on the Nabal. Do you have any information you can suggest? Also, my water bill is killing me every summer. My Avocado trees are watered every 3rd day for 4 hours by mini-sprinklers, once the rains are over. Can you suggest how to determine the proper amount to apply? Thank you, Tim

Sorry, one more question. Occasionally a branch will turn black and die. Is this something I sould worry about? Thanks

Sorry Greg, don’t know why I got your name wrong.

Hi Tim,

It’s usually nothing to worry about if a branch here and there turns black and dies. This happens naturally.

As for watering, check out my post here: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/how-much-and-how-often-to-water-avocado-trees-in-california/

Nabal has always had a reputation of not bearing consistently. I don’t know that there is anything you can do about your Nabal because it seems mostly due to the location of the tree. But if the tree flowers yet doesn’t set much fruit for you, I’d consider putting an A-type pollenizer tree by it or grafting a branch in, and I’d also try to enhance the pollinators near the tree by growing flowers.

See this post on growing flowers to bring in more pollinators: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/growing-a-bee-garden/

Well, I decided to purchase a Fuerte and its in the ground now, about 12′ from my Hass. I can’t find the comment now, but I seem to recall reading somewhere in your blog that you felt the Fuerte taste was “next level” for something similar, compared to Hass. I’m looking forward to trying it.

I write this because I had an interesting experience when I purchase the tree today. The clerk asked me, “have you tried a Fuerte before?” I haven’t ever had an avocado that was noticeably better than a good Hass, so I responded, “I likely have, from the grocery store.” He responded, “grocery store avocados are not the same. The Fuerte is next level. Hass is good, but Fuerte is in its own league. It has this nutty, buttery flavor” Guess you and the South African farmer are not the only ones who love them.

They are hard to find here in Santa Barbara, only on nursery sold them. I ended up with a 5 gallon size, would have bought a 15 gallon if I could find one. With all the rain we have had the past month, the tree should get a good start. We were at 10.8″ for the season on March 11, today we are at 16.2″, including 2.5″ in the past week. Totals at my house are typically ~25% higher than those numbers.

Thanks, Matt. That is fun to hear. I still can’t put words to it, but sometimes there is just something about the taste of a Fuerte that I like more than anything. And it’s good to know that it’s not only my imagination.

I found a smallish Fuerte avo from the tree back in September. I planted the tree two and a half years ago from a 5 gallon container (see above). We were gone a lot that month, I’m guessing the tree dropped it during the heat wave, I know my Hass dropped a couple fruit also.

I decided to put the Fuerte on the counter to try it. I know September is REALLY early to pick Fuerte (fruit set in spring 2022), especially in Santa Barbara. Well, I had it with lunch today and it was very good. Maybe a bit on the watery side compared to my just finished Hass (1 more still to eat), but it does have that nutty taste I saw mentioned above.

I’m super excited to get to finally sample a fruit from this tree, as well as to let the rest get bigger and see the difference in constinancy (sort of watery inside). Guessing I’ll try another around Thanksgiving.

Hi Greg,

I have a Fuerte that was planted out of a 15 gallon container 1 year ago. It is growing well and is now about 6 feet tall. Is it normal to only have a a few flowers on it right now mostly on the lower part of the tree? I’m wondering if the new growth starting to form will include flowers that will bloom into May/June. Is the characteristic of a drone Fuerte that it doesn’t put out a lot of flowers or just doesn’t set a lot of Fruit?

Hi John,

Good question. I’ve seen Fuertes have different flowering patterns. I’ve seen some bloom intensely, seemingly all at once, but more often I see Fuertes blooming moderately over a long period. Mine is doing this right now.

Sometimes floral shoots will appear from the side at the base of a shoot of new leaves. In other words, the leaves emerge first and then the flowers emerge. But it isn’t a long delay. It’s not that the leaves emerge and then a month later the flowers emerge. I’ve never seen that. So I’d guess that it’s more likely that your tree is just not going to flower on the upper part this year.

Of the drone Fuertes that I know, I’ve never seen them flower intensely. But I can’t say for sure whether that correlation is always there. With other varieties however, or avocados in general, the amount of fruitset is highly correlated to the amount of bloom. Avocados set fruit on a small proportion of their flowers, no matter how many flowers they have.

Greg,

Thanks for the response. I believe this tree came from Durling nursery which i purchased from Home Depot. Wouldn’t they be grafting from a fruit producing tree instead of a drone? Or is it not that simple and a fruit producing graft could end up being a drone?

Thanks again!

Hi John,

This is a great topic. I’m not certain, but I would guess that Durling is taking budwood from Fuerte trees that have demonstrated themselves to be productive. Durling has been around for a long time and has an excellent reputation.

Unfortunately, that seems to not be a sure way to produce a new Fuerte tree that produces well. That seems to help, but not ensure it.

You can read some of the documents that I linked to in the post to find details about this issue.

I’ll tell you that what I’m calling my drone Fuerte has NEVER flowered. I’m in the country and keep bees, so I have plenty of pollinators. It looks very healthy and green otherwise, but I’m going to shovel prune it this year and replace it with something else. My Pinkerton–which I got to complement the Fuerte–is half its age and is already producing. Heartbreaking, as I’ve invested so much time in the Fuerte. I’d buy another Fuerte but I’m afraid I’ll get another drone. Is there any way to tell if a Fuerte is a drone?

Hi MT,

I wish there were a sure way. I don’t know that there is, but people have tried a few things that have seemed to help.

One is taking scion wood from Fuerte trees that have demonstrated themselves to be very productive. And some even go so far as to take scions from particular branches that have borne much fruit.

Some help has also been found in using certain rootstocks, but it seems that the scion source is more important than the rootstock.

See: http://www.avocadosource.com/cas_yearbooks/cas_59_1975/cas_1975-76_pg_122-133.pdf

And see: https://www.avocadosource.com/CAS_Yearbooks/CAS_79_1995/CAS_1995_PG_157-164.pdf

Also see: http://www.avocadosource.com/Journals/ITFSC/PROC_1976_PG_36-42.pdf

I think that the best way to avoid getting a drone and to give the best chances at a productive Fuerte is to buy a tree on a clonal rootstock that has proven productive for many different scion varieties. See my post on rootstocks: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/avocado-rootstocks-what-do-they-matter/

How do you do this as a home grower? Not easily. The only nursery I know that sells clonal rootstocks to home growers is Subtropica in Fallbrook, San Diego County: https://www.subtropicanurseries.com/

What I would not do is buy another tree from a typical retail nursery or a place like Home Depot. I bought my own drone Fuerte from Home Depot. Not that you can’t get a Fuerte tree that produces from these places, but I think it’s a bit less likely.

Great article! I recently bought a home in SoCal zone 10b, with a mature avocado tree based on my research I believe to be a Fuerte. The tree was so loaded with fruit this year, that even after eating it at almost every meal, giving it away to family, friends, coworkers, and neighbors, there is still fruit on the tree.

My tree was covered in blooms in mid-March and just humming with bees buzzing around. Then we got some more rain in April and it seemed like most of the blooms ended up on the ground. Hoping we get another great year in 2020.

Question for you… there are probably 2-3 avocados dropping from the tree on a daily basis. Do you recommend that i just harvest everything now? How does leaving old fruit on the tree affect future fruiting? Thanks! Enjoying your blog since I found a link to it on reddit.

Pictures of the tree in March: https://imgur.com/gallery/OvSbE2M

Hi Klancy,

What a beautiful tree! You are so lucky. Most of the blooms on an avocado tree end up on the ground no matter what, that’s the reality. Researchers have estimated that only about one or two in a thousand avocado flowers on a tree end up growing into a mature fruit. But looking at the amount of bloom on your tree, I’d say it’s for sure going to have plenty of avocados for next year too.

Researchers have found that leaving mature fruit on the tree very late in the season reduces the following crop somewhat, but I wouldn’t worry about this with your tree. You obviously don’t need as many avocados as this tree can possibly provide. I would just pick and eat them as you want. At some point, they’ll start tasting a bit overmature and cheesy, but enjoy them while they last!

Hi folks, I grew up with 5 Fuerte trees on my parents property. All produced good crops and none of them had any real treatment to the tops of the soil over their roots. I tried an experiment on one tree in the tree in the corner of the yard. Rather than throwing out grass clippings, raked leaves, weeds and sticks, I put all of that green waste under the one avocado tree in that corner of the yard; about 2 feet high. Really big bugs and nice smelling black composted soil started forming after about a year. About a year after that we had more avocadoes being produced from that one tree than all of our other trees combined. You all may not have to rip out your seemingly non producing trees. Just give the trees what they are known for wanting: loads of green mulch above their roots. Your trees should pay you back kindly. Oh, the location was the Pasadena area.

Thanks for sharing this, Craig. What I like most about it is that you didn’t bother composting the materials elsewhere and then applying the compost under the tree. Many times I’ve also built piles of plant materials under or beside an avocado tree and scratched into the pile a year or so later to find the tree rooted throughout the decomposing material. My experiences perfectly align with yours in this way.

Love your posts and videos, very informative for a new grower such as myself. I had a question about planting avocado trees. I live in Poway in an area with great soil. There was a 4 foot avocado tree already planted in the middle of the yard, I’m guessing a Haas but can’t tell. Based on your other post and in doing more research I planted a Reed and Fuerte. The Reed is about 10-12 feet away from the Haas and about 28-29 feet from the Fuerte (there’s an orange tree in between) and Fuerte is about 33 or so feet away from the Haas. I would have loved to plant them next to each other or closer (~20 feet) but there’s already mature trees in every other planting area in our yard unless I plant them 10 or so feet apart. My question is do you think the Fuerte is too far apart for cross pollination for the Type A trees or should I switch the Reed and Fuerte? I know they don’t need another tree to bear fruit but just wondering while they’re still small enough to dig up and move (only in the ground less than a week).

Also, the Fuerte gets about 7-8 hours of sunlight while the Reed gets 6 hours but I’m going to prune the trees around the Reed so it gets more going forward. Not sure if they have different sunlight requirements or anything. Thanks!!

Hi Marc,

Thanks. You’re almost my neighbor! The ideal arrangement would be to have the Fuerte in the middle. If it’s easy for you, I’d go ahead and dig them up to rearrange. But if you don’t they’ll still have plenty of cross-pollination opportunity at that spacing.

I’ve never noticed a difference in sunlight requirements between the varieties, but I will say that Fuerte and Reed seem to handle high heat slightly better than Hass.

Thanks a lot for your feedback, I really appreciate it. Without your posts I think I’d be pretty lost trying to grow new trees in my yard.

They’re actually in more of a triangle, with the Reed being at the 90 degree angle. Reading your post about bees pollinating different tees 50 ft apart maybe I’ll leave them.

Switched them. Hopefully they do well. Thanks!

I am curious what kind of trees you have when you say “I would have loved to plant them next to each other or closer (~20 feet) but there’s already mature trees in every other planting area in our yard…” ? Are they something desirable such as fruit trees or something else like pine, eucalyptus or pepper trees?

If it is anything but fruit trees, I would remove them since they will rob your avocados of irrigation water and sunshine.

Thank you for this post. While I was renovating my home in 2014, one of the construction worker brought me an avocado tree he started from a seed. He didn’t know the type but the avocados he brought me were huge, with smooth skin and very tasty. The tree started blooming 3 years ago but each year my excitement subsides after all blooms fall off. This year, I started seeing buds (yay) but half are dropping. I see a few survived and growing very fast. 2 weeks ago it was barely 1/2” but yesterday it is already 2” long and 1” diameter.

I still don’t know what type it is, but it looks like a fuerte. I only have the one avocado tree but it is planted near a mango, a pomelo, 2 types of guavas and many different types of oranges and lemon trees.

I am in Orange, Ca.

My Fuerte is starting to make me angry! Now for the second year in a row, it has produced hundreds of pea sized avocados..and then dropped them all! The tree has very little tip burn and looks very healthy. I increased the watering this year hoping to solve the problem, but no luck! I also live in Ramona, in the Estates at about 1,700′ elevation..any ideas?

Hi Scott,

Believe me, I can imagine your anger at your Fuerte. Mine is six years old, was 15 feet tall, bloomed moderately this spring but held zero fruit. This spring was its last chance to show me a real crop. Last week I cut it down to a stump. I’ll be grafting onto the sprouts that grow this summer.

For your Fuerte, it might benefit from the pollen of a second avocado variety nearby. I know of some Fuertes that have increased their fruiting when a pollenizer was added. However, this hasn’t been the ticket for mine. I had a couple different varieties blooming nearby and it didn’t help.

As mentioned in the post above, some Fuertes are mysterious drones. They just never produce well. I’ve concluded that mine is such a drone.

But if yours is only a couple years old and it at least set many pea-sized avocados this year, then I’d guess it has potential to fruit well. You might just need to give it another year or two to add canopy size. Fuerte trees are never as precocious as some other varieties such as Lamb, GEM, Pinkerton, and Hass. I have a friend who lives in our area with a grove of dozens of varieties, and his Fuerte was one of the slower varieties to hold a heavy crop. But last year, after about four years in the ground, his Fuerte set an excellent crop.

Thanks so much for your reply. My tree is about 10yrs old and may end up just being an ornamental in my orchard!

Hi,

I ran across your website today. I grew up on a 6 acre lot east of Escondido, CA overlooking San Pasqual valley that was planted entirely with Fuerte in the late 40’s. When I was a kid, we had over 300 trees that were upwards of 35′ to 40′ tall with continious canopy. Unfortunately as H20 got more expensive, we cut back on acreage and also stumped most of the trees and grafted hass which had a better selling price primarilly due to better packing and longevity to market. We kept about 15 trees for personal consumption and they are still going strong at 70+ years. I read that Avocado trees can live 400 years.

Fuerte have a far superior nutty flavor to Hass in my opinion. The oil content is higher. I always enjoy turning someone on to a perfectly ripe home grown Fuerte, the response is always the same. Wow!

Thanks for your nice blog.

Andy

Hi Andy,

Thanks for sharing this. What a youth! What a setting in which to grow up! Fuerte is unique in that so many people are nostalgic about it. No one is nostalgic about other avocado varieties. If you’re a Fuerte fan, then you often don’t just like the taste of the fruit but you also have memories of climbing in the trees when you were young, etc.

I’d love to see those old Fuerte trees. I bet their branches have so much character, like an old live oak.

I have a 40- year old avocado tree that was planted by our home’s previous owner. It yields several hundred, maybe a thousand, avocados per year. I pack them in paper bags and leave them on neighbor’s doorsteps with a note where they came from. They are creamy and buttery with skin like the Fuerte. Actually a neighbor who received a delivery sent me this post.

Often times late in the season the pits have already sprouted. I soak them, plant them in pots, and give them away to anyone who wants them. I want to keep this delicious species going and, who knows, maybe someone will leave some at my door in the future.

Do you know how I can determine for sure if these are Fuertes?

Our tree lives happily in Hacienda Heights, CA. This year’s baby plants will be ready in a month or so if anyone wants them. We also have about 10 or so falling every day so I’m happy to leave a bag of them out for anyone who wants them.

Hi Lynn,

I wish I were your neighbor. I hope to be like you to my neighbors. I love how much you appreciate your avocado tree.

Off the top, I would guess that you do have a Fuerte. You’re in an area where many Fuertes have been planted over the last century, and where they produce well.

Some signs that your tree is a Fuerte are if the new shoots have red specks on their stems; the harvest season is about over now (the seeds sprouting inside the fruit shows that); the bottom of the fruit is often asymmetrical, slanted on one side; and the tree makes some fruit that don’t have seeds, and that look like miniature cucumbers.

Hi Lynn,

I know it’s been a nearly a year but I just saw your comment and was hoping that you would see this! I would absolutely love to get some scion wood from your avocado tree! I have a Fuerte tree (I think) that has been growing for years and has not been fruiting well for me. I am hoping that if I am able to get some good scion wood to graft onto my tree, it will be able to finally produce for me. Would love to hear back from you 🙂

Hi Greg. I recently discovered your page and I love all of your content. I am right up the 5 from you in south OC. I recently bought a 15 Gal holiday (about 6ft tall)to put in a 16×20 raised bed to the side of my driveway. I staked it with two stakes and have straps going both directions about 2/3 of the way up the tree. It has been in the ground a couple of months and seems to be really healthy. When do you think it will start flower? My guess is not for another year or so.

I was thinking of grafting Fuerte scion wood to one or two of the branches so I can have an A and B on the same tree. Do you think this is a good solution if I do not have space to plant any other trees on my property. There are some neighbors a few hundred yards away who have an avocado tree but I am not 100% sure what variety it is or if it is too far away to help pollinate.

If you thing grafting a Fuerte or some other B variety to it is a good idea, do you know anywhere to get scion wood?

Hi Scott,

I bet your Holiday will flower this coming spring, probably starting around March. But you’ll be lucky if you get fruit to set and hold all the way until maturity, which would be in the summer of 2022. My experience with Holidays is that they really tease you in the early years and don’t hold their fruit well. I hope you’re lucky though!

Grafting Fuerte onto your Holiday could work to enhance the Holiday’s pollination — it most definitely couldn’t hurt.

As for where to get Fuerte scion wood, you can probably locate a Fuerte tree not far from your house. If you’re in San Clemente by chance, I can even give you the addresses of some Fuerte trees. Otherwise, you can attend scion exchanges of the Orange County or North San Diego County chapters of the California Rare Fruit Growers in the winter, or you can make a request on the Tropical Fruit Forum: http://tropicalfruitforum.com/

Around March is the easiest time to graft avocados.

Hi Greg. Glad I stumbled on this post looking for a post I could link to one on my site about Fuerte’s. I am planning to landscape a new house and planning for citrus trees and 1 avocado. I thought I was going to plant a Haas but now I’m not sure! Hard decision! Not sure the Fuerte is the best choice. Suggestions?

Hi Sally,

It depends a bit on where the house is located, but most likely a Hass would be my suggestion. Here are some reasons in my post “What’s the best kind of avocado to grow”: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/whats-the-best-kind-of-avocado-to-grow/

Hi Greg, thank you for responding. A Hass is what I was planning. At least you’ve given me confirmation and I love the taste of them too. We are about 5 miles off the coast, and often get nice air off the ocean because of geography. We are in South Orange County almost to San Juan Capistrano

Hi Sally,

You’re in an excellent location for Hass to perform well.

Hi Greg! I just purchased a home in SoCal that has 2 Fuerte Avocado trees. I picked some of the avocados off of the tree 2 weeks ago, put them in a brown paper bag in my pantry, and they’re still hard as rocks! I cut one open and it was bitter. How long do they take to ripen and/or what is the best way to ripen them, and how do you know when they’re ready to pick? I didn’t want to wait until they fell to the ground in case rats or other pests got to them! Thank you!

The avocados from my Fuerte tree don’t ripen for 2-3 weeks. I just keep picking them on a rotating basis. I wait until they’re the size I like (pretty large), pick them, and set them aside, knowing I won’t be able to eat them for a while. The thing I’ve noticed with the Fuerte tree is it needs patience. They take a long time to bear fruit, and a long time for that fruit to ripen. It’s worth it though. Best avocados I’ve had.

Thank you, Jessica. I am curious, when you pick the avocados from the tree, do you just pull them off or do you have to clip them by the stem/branch? We picked all of them off of the tree in Oct/Nov and I am noticing that the tree is starting to get little buds/flowers – I suppose that means new ones are growing? Thanks for your help! This is my first time owning a fruit tree. Do yours bear fruit every year?

This happened to me with my Pinkerton, too. I am in Southern CA. The fruiting season is supposed to be December-April, so the first year I picked all 6 fruits in January and put them in paper bags. They were good size, but. they never ripened This year, I picked one in February 1, one at the end of February, one on March 1 and one on March 15. Turned out March 15 was the magic date for my microclimate.

Hey Molly, from the article above, “Early set fruit might taste good starting in November. I think of Thanksgiving as the day to start testing avocados from Fuerte trees. And even in June there can be Fuertes that still taste good. But the heart of the normal Fuerte harvest season is approximately January into April for most of Southern California.”

Thanks, Matt!

I’ll add that for this past Fuerte season, the first one that I ate that tasted great was on February 17. But I had been eating pretty good ones throughout January. The last one I ate was on July 7, and it still ripened well and had quality taste (although not as good as the early spring fruit).

Great information on the Fuerte Greg, thank you. I planted mine with a Frazer, Hass and Reed in my backyard. Purchased from Avopro in NZ in 2016. Today I found my first Fuerte on the ground. It’s huge, and I’m looking forward to avo and tomato on toast for breakfast.

Good info. I live in Morgan Hill, just S of San Jose. We have 1 Fuerte. One winter, we had a night down to 17 F followed by a night around 22. Tree lost all its leaves and most small branches. But trunk and roots survived. Lost all fruit on the tree and no blooms the next year as it grew back. But the following year it produced several hundred and continues to fruit well, but not on the same branches from year to year.