Captain L. L. Bucklew began planting mango trees in Encinitas, San Diego County, before World War II. By 1956, he was up to 172 trees. Bucklew’s grove was the first commercial planting of mangos in California, and today, fourteen of these historic trees are still growing and fruiting. I visited them a couple of weeks ago.

Their bark is cleaved and furrowed as you’d expect on 80-year-old trees, but if you’ve seen mango trees in the tropics then you’d be surprised that they’re not 40 feet tall. Some are around 25 feet tall while a few are not much higher than a basketball rim.

California mango trees do not ever grow to make massive outdoor living rooms as they do closer to the equator. But surprisingly, Captain Bucklew’s trees are not all bigger than some younger mango trees I’ve seen in the state – even though they are California’s oldest living mangos, as far as I know. The trees have had variable care after Bucklew died in 1982.

Who was Captain Bucklew?

Born in 1880, Bucklew persuaded his parents to allow him to join the 3rd United States Cavalry so he could fight in the Spanish-American War when he was 18 years old. In the cavalry Bucklew trained to ride horses bareback and was under the command of General Joe Wheeler, who was a Confederate States Army officer during the Civil War. To me, this illustrates just how long ago Bucklew was alive.

Bucklew was sent to the military action in Cuba and then the Philippines. And in these two countries he got his first taste of mangos. Having learned Spanish while in those countries, Bucklew was then hired by the U.S. Department of Commerce to explore opportunities for the lumber industry in Central and South America. He spent 18 months working throughout that region, and was there exposed to yet more mangos.

Bucklew returned to his home state of Missouri about 1915 and was soon asked to organize men for an impending U.S. entrance into a war that was already underway in Europe. Bucklew organized the 128th United States Field Artillery. So he was an Army Captain, and for the rest of his life he was known as Captain, Captain Bucklew, or Buck to some of his peers.

Nearby in Missouri was the adjoining 129th Field Artillery regiment, in which belonged future president Harry S. Truman.

Bucklew and Truman

Bucklew and Truman got to know each other as they fought side by side in Europe during World War I. Beyond the war, they kept in touch for the rest of their lives.

In an interview given much later, Bucklew recalled a visit to Truman in the White House: When he entered the presidential office, Truman called out, “Fellows, we have a Republican with us today. We’ll give him hell.” Bucklew and Truman then shared drinks from a bottle of scotch. The aides that surrounded them referred to Truman as “Mr. President” and Bucklew could see that this irritated Truman, who eventually said to Bucklew, “I can’t be myself around here.”

Bucklew had gone in a different direction with his life after the Great War. Rather than into politics like Truman (who was president from 1945 to 1953), Bucklew went out to California “just to make a living and not try to get rich . . .”

Captain Bucklew’s mango plantation

Captain Bucklew arrived in California in 1933. He became a member of the California Avocado Society (then called the California Avocado Association), and in the Society’s 1940 Yearbook he reported on his mango plantings — which began in 1936 — in an article titled, “Mango Trials.” Bucklew’s property in Encinitas was just up the hill from the ocean, about a mile and a half from the water, on a west-facing slope. It was ten acres that were free from frost.

Bucklew had first checked out the few individual mango trees that had been planted around San Diego County before planting his and concluded “it was worth while to make a commercial [mango] planting.”

By 1940, he had 150 trees growing. Some were grafted trees while many others were seedlings. The varieties Bucklew had going included Haden, Cambodiana, Sandersha, Bombay, Gordon, Florida Apple, Johnson, Brooks Late, Caraboa, Filipino, and Manila. He had brought them in from all over the globe: Jamaica, India, Mexico, Florida, Honduras, Hawaii, etc.

Captain Bucklew began receiving assistance in his mango endeavors by pioneers of tropical and subtropical fruit exploration such as David Fairchild of Florida and Wilson Popenoe of California.

Again in 1956, Bucklew reported on his grove in the California Avocado Society Yearbook of that year in an article titled, “The Mango in California.” At that point, he had been growing mangos on his coastal Southern California property for two decades so it had become clear whether his climate and soil were suitable, as well as which varieties were suitable.

While his deep sandy soil grew the trees well, and he found no challenges with irrigation, fertilization, pest or disease control, Bucklew discovered that the proximity to the cool ocean kept his climate too mild. Only in warmer-than-normal springs did the trees get ample fruit set.

And though he was trialling 32 varieties, “some varieties mature very slowly, or not at all,” he wrote. Their fruit grew so slowly without the required heat that they were barely ready to pick in December when the nights had cooled down or they never completely matured before winter arrived.

Bucklew realized that he needed “early” varieties. He sought varieties that matured in April and May in tropical locations. He found one such variety from Florida called “Earlygold” and it showed great promise in his grove, maturing its fruit in November. Earlygold was also a high quality mango to eat with yellow skin, excellent flavor, and very little fiber.

A decade later, a group from the California Avocado Society toured Captain Bucklew’s property and tasted his Earlygold mangos, which by then he had settled on as the best variety for his location. (As reported in the 1966 C.A.S. Yearbook, page 17.)

When I visited Captain Bucklew’s property over a half century after this, I found more Earlygold mango trees remaining than any other variety. Through the years, Bucklew had grafted over many of his other varieties to Earlygold.

Also in the 1956 report, Bucklew passed on that he had had more success growing trees from seed compared to transplanting large seedlings or grafted trees brought in from out of state. Scions “develop well on locally grown seedlings,” he wrote. (Bucklew used mostly Manila type seeds for rootstocks.)

Captain Bucklew’s advice was sought out and appreciated as he had “made a more thorough study and field trial of mango than anyone in California” at this point in time, wrote Wells Miller in the California Avocado Society Yearbook of 1961.

By the way, if you ask around today you’ll find that many experienced backyard mango growers in California still affirm Bucklew’s view that mangos here usually grow better if planted as seeds or small seedlings and then allowing the seedlings to fruit or grafting them to a desired variety only once they are established. This is opposed to planting grafted mango trees. The difficulty of planting grafted mango trees is that they immediately try to flower and make fruit rather than grow a framework of branches first (as seedlings do).

The Swami’s mango tree

When I toured what is left of Captain Bucklew’s mangos I was accompanied by his great grandson, Joseph Weber. Weber told me that “granddad” never made a lot of money from selling mangos and his second wife encouraged him to replace any sickly mango tree with an avocado.

Mangos are thought to have originated in or near India, and among those locals who bought mangos from Bucklew were immigrants from India. A couple miles from the grove in Encinitas is a Self-Realization Fellowship center on the bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, below which breaks a righthand surfing wave called Swami’s. It is named after the founder of the center, Paramahansa Yogananda.

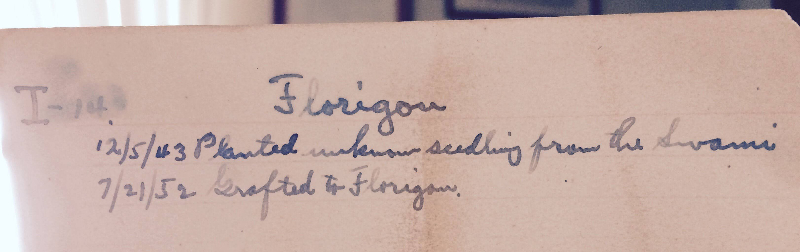

Bucklew kept notecards about all of his trees, and one of the cards reads that in 1943 he planted a seedling given to him by “the Swami.” The tree grew and was later grafted to a variety called Florigon.

“The Swami’s mango tree” is still alive and making Florigon fruit today. It is the only tree for which the family has made a sign.

Weber told me that recently he brought a handful of mangos from the Swami’s tree to the SRF center and shared them with the staff, along with the story about the tree. They hadn’t known about it and were greatly impressed.

2022

Captain Bucklew died at the age of 102, and what remained of his Encinitas property was passed on to descendants. All but one parcel has been sold off and developed. The parcel upon which Bucklew built himself an adobe house, however, was given to Joseph Weber’s mother (Bucklew’s granddaughter), who then passed it on to Weber.

As a kid, Weber lived in Chula Vista but spent weekends with his great grandfather at the farm. Weber’s mother later ran a nursery on the property. They knew the land and the trees and cared about them. More than mangos and avocados, Captain Bucklew had been an early grower of litchis and macadamias too.

Weber and his wife now live in the adobe house that his great grandfather built. And he cares for the remaining mango trees that granddad Captain Bucklew planted before most of us were born. As they stand, the remaining varieties are Earlygold, Florigon, Saigon, Macpherson (which was developed by Bucklew), Julie, Zill, Jonathan, and a few unknown.

In this video I walk among Captain Bucklew’s mango trees:

You might also enjoy reading my post, “California-grown mangos.”

If you’re interested in growing mangos yourself in Southern California, check out this discussion on the Tropical Fruit Forum. Also watch a recent presentation on the topic for the California Rare Fruit Growers, Orange County chapter.

I’m able to spend time writing posts like this one about Captain Bucklew’s mango trees because of the kind support of readers like you. See how you can say thanks and keep the Yard Posts coming HERE

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

Awesome post! (Would love to hear more on Hwy99 in the future too)

The mango i planted died and i assumed my area wasn’t tropical enough, but i guess thats not the case since i am only a few miles from the Captain’s trees. Re-adding mango to my list, thanks Greg.

Thanks, Colin. Your situation is not so dissimilar to mine. I killed a few mangos at my place and then gave up for a while, but seeing a nice tree growing in a neighbor’s yard spurred to me to think hard about why my trees didn’t thrive and now I’ve got a few new trees growing again.

We’ll be on the 99 next week, to Fresno and then on Yosemite.

Hi Marie,

Look forward to hearing your observations. And have fun in Yosemite!

I agree that planting a potted mango gets you tons of flowers year after year and very little branch and scaffold growth. A few years ago I began aggressively pulling fruit and flowers off to let the tree grow, leaving only a few fruit to enjoy. My tree is close to eight feet tall now and has enough branches to let fruit stay. It’s still a spindly tree compared to these here but finally big enough to let fruit stay. I heavily thin it, though as all it wants to do is fruit. It’s a Manila mango. If I remember tomorrow I’ll send you a picture.

I planted a 5 gallon Mango Manila in May 2019. I harvested two fruits on Oct 2021. Fruit very good, waiting to see what happens this year. I’m in Concord , SF Bay Area.

Love the posts Greg! I’m not sure if I missed it, but would you ever consider doing a post on growing Mango’s in Southern California (tree care, similar to what you’ve posted for Avocados)? I live near you and tried to plant a Keitt Mango and it’s close to dying due to disease so would love to hear about your experience growing and what you do to keep them alive and produce fruit (if you’ve gotten any yet). Thanks again!!

About 10 years ago a friend gave me some Ataulfo mango that I now know were premium fruit – perfect! I was never interested in mango until I ate those. Then I noticed Costco was selling the Ataulfo mango, so I bought some. They were good also, but less than premium. I planted about 8 seeds and grew some baby trees. None of the trees made it passed about 18″ high. I figured that variety would not grow in San Diego, so I gave up on it and other mango varieties were not worth growing to me if I could even get them to grow. Cherimoya grows nicely in my location and I have roughly 6 trees producing every year, but you do need to manually pollenize them. I think some fruit trees can’t take the dry heat we get – the reason I never grew a coconut palm.

Greg and Richard, many years ago on a trip along the sea of cortez i stayed a couple of nights in a campground owned by an older gentleman. He was growing coconut palms. He told me his secret was to put a sack of sea salt in the hole when planting. It mimicked the beach 🏝️ island environment. always wanted to try it, but I’m on two acres in Ramona near high school. But would love to try mangos, papayas, bananas,and avocados. If there’s a variety that can take the cold, would love to buy some.

Love your posts – new subscriber

Hi MaryAnne,

There in the flats near the high school it does get pretty cold a few nights each winter, but I’d say that all of those plants are still worth trying. Just yesterday, I was driving near there and saw some good-looking bananas in a yard, close to a south-facing wall. And I’ve seen a large, old avocado tree near there of a variety I couldn’t discern.

By locating the trees in the warmest spots and protecting them through their first few winters, you would probably be able to get production out of those plants in most years but not all. Some winters would zap them but they would grow right back if established enough.

And very interesting about the coconut palms! They sure do like to grow right in the salty sand so it makes sense.

This is so cool. I have friends in the food and natural fruit business and live in San Diego. Did not know you could grow mangoes in SD and was also reading about the Sindhu mango variety or the almost seedless version. Have you tried to grow those?

I planted a sprouted mango seed a few weeks ago. It was already sprouting and sending out roots when I peeled the fruit. So I had high hopes for it. Something (probably a rat) removed the seed from the pot and the seed disappeared.

I just planted another sprouted mango seed and put some fist sized stones on it to weigh it down. Allowing the sprout to poke up between stones. Hopefully this will keep the seed from being taken and eaten.

I have grown Glenn and Nam Doc Mai mangoes in Escondido for years and both do very well. Both creamy smooth with no fiber and the two together cover just about 4 months of year with fruit. Just ate last ones for year. Delicious!