A few weeks ago, on our way back down from a friend’s wedding in Oregon, we decided to take our rented RV on Highway 99 rather than the faster Interstate 5. I should say that I decided to take Highway 99. From Red Bluff in the north to Bakersfield in the south, the 99 cuts through 400 miles of agriculture, and I’m interested in agriculture.

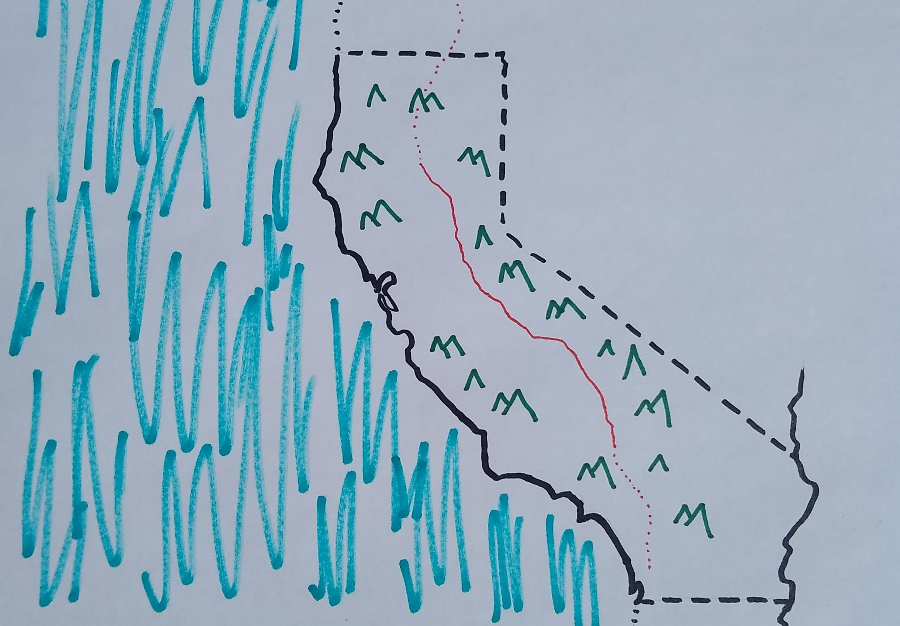

You know that, topographically speaking, California has a humungous swale carved out of its middle: the great Central Valley. Highway 99 is the original route up and down that Central Valley.

It had been many years since I’d travelled on some sections of the 99, and I can’t even remember the last time I drove on the part above Chico. This time I would drive the whole 99 continuously, from top to bottom. How would the crops change from the top end to the bottom end?

Up above Chico it was all olive trees, almonds, and walnuts. Olives and nuts. There was no fruit; there were no vegetables. Only near Chico did the first fruit tree orchard appear, one of plums or pluots. I wonder why they don’t grow fruits or vegetables, or much anyway, up near Red Bluff.

Citrus first appeared near Gridley, well below Chico. And then surrounding Gridley I saw orchards of persimmons and peaches or nectarines also.

Nearer to Sacramento, rice fields were aplenty with their telltale attributes of being perfectly flat, bounded by earthen berms, and flooded with water.

Many vineyards started at Lodi, some grapevines being head-trained, some on trellises, some very old with thick trunks, some thin and newly planted.

More citrus took up land as we got below Fresno and approached Bakersfield. We passed a giant building complex with an even bigger freestanding wall advertising Halos brand mandarins. Once home I looked into that Halos building. Halos is owned by The Wonderful Company, and that building is claimed to be the world’s largest citrus packing facility. Wonderful claims to be America’s largest citrus grower.

Also becoming more common in the south were feedlots of cattle. Innumerable black and white cows were mostly huddled near shade structures and feed troughs, surrounded by acres of baking bare land — except for their excrement — and manure lagoons. It smelled to high heaven. This is the dairy industry, but it didn’t smell like milk.

I was reminded of a passage from Joel Salatin: “Any food production system that stinks up the neighborhood — regardless of how rural — is unacceptable . . . If you ever smell manure, you’re smelling mismanagement.” (Page 27, You Can Farm.)

I’ve always kept this passage in mind with my tiny chicken flock. But having a nose that doesn’t work well, I have to be extra attentive because once I can smell unpleasantness in my chicken pen it’s surely long overdue for an addition of wood chips to cover and compost the manure.

Close to Bakersfield, the south end of Highway 99, there were still almonds. Almonds were the common thread, being grown from the top of the 99 to the bottom. Someone in every county was growing almonds, from Tehama to Kern.

But finally also near Bakersfield there were significant swaths of vegetables: onion, garlic, carrots, tomatoes, corn, watermelon. And when I say significant swaths I mean monoculture masses.

Monoculture

I imagined what it would be like if I were a bug that fed on garlic. I would be in heaven here if I found the garlic field. I could eat all I wanted for acres and acres, not being without garlic to eat for more than a few inches between rows as I meandered and masticated and proliferated.

I also imagined what it would be like if I were a bee in one of these grand monocultures of hundreds of acres of almonds. I wouldn’t be. Even though there would be tasty flowers to feed on for a few weeks each winter, there was nothing here in early June, nor was there anything to eat for the other 50 weeks of every year. That’s why bees don’t live in California’s almond orchards, and that’s why honey bees are trucked in by the billions in order to pollinate the almond trees each February and March.

But those bees best not fly over to the wrong grove of mandarins and sip the nectar of their beloved citrus flowers. You know how those mandarins that you buy in stores — such as those sold under the brand Halos — never have a seed inside? Sometimes that’s because the mandarin variety is naturally seedless while other times it’s because bees have been forbidden from visiting the mandarin trees.

(The mandarin farmers and the bee keepers of the Central Valley have had a challenging relationship because the bees can make some mandarins have seeds. See here and here.)

On one hand, I looked over these green monocultures as I drove down Highway 99 and thought they looked verdant. They looked productive. There was beauty.

On the other hand, I kept recognizing how unnatural and imbalanced and vulnerable were such vast patches of a single plant.

Chemicals

This made sense of the billboards. Along the entire stretch of 99 were billboards advertising “protection” for rice or grapes or some other crop. Here’s one:

“Stop damage before it breeds . . . Target pests with Suterra CheckMate.”

Once I got home I looked up Suterra CheckMate. It’s a product used on insects in fields of citrus, grapes, cabbage, apples, peaches, tomatoes and more. And Suterra the company? It’s also owned by Wonderful.

(The Wonderful Company is owned by a husband and wife who live in Beverly Hills. They own a lot more than Halos and Suterra. For example, they also claim to be “the world’s largest grower and processor of almonds and pistachios.” You can dive into a deep hole reading about them. If you care to start: here’s one article and here’s another.)

I looked up one more company advertising pesticides on the billboards of Highway 99, this one called Nichino America. It is owned by Nihon Nohyaku, an old company from Japan that started making agricultural chemicals there in the 1920s and has now expanded into pharmaceuticals, according to its website.

How much of these concoctions made by Suterra and Nichino America and the others were being used in the fields of the food plants along the 99?

Irrigation

Whenever I drive by a farm I pay special attention to their form of irrigation. I was made especially attentive after seeing the electronic message boards along Interstate 5 starting right below the Oregon border glowing, “SEVERE DROUGHT, SAVE WATER, SAVE CALIFORNIA.”

I noticed that all of the orchards on the north end of Highway 99 were irrigated with mini-sprinklers. A couple of orchards were over-irrigated with mini-sprinklers, as was obvious by puddles in between rows and moss growing in spots.

But water up north is more abundant. You see it in the size of the Sacramento River, which the 99 parallels. You see it in the size of the Valley Oak trees growing naturally here and there, you see it in the dark brown color of the dirt.

As you drive south, the dirt fades to the color of sand. The native trees disappear. Well before Bakersfield it is clear that you are in a desert.

The first orchard on drip irrigation that I saw was near Madera, south of Sacramento, south of Stockton. At that point, drip became more and more common as we approached Bakersfield.

Elevation

It had never occurred to me how low in elevation the Central Valley is until we entered Yuba City, which is about halfway between Chico and Sacramento. Upon entering, the sign said that the elevation was 60 feet. I thought: Only 60 feet in elevation? But we’re so far inland.

After Yuba City at 60 feet, I found that Sacramento was signed at even less, 30 feet in elevation. Below that, Stockton was only 13 feet.

I tried to make sense of this. As I described the Central Valley earlier, it’s a swale carved out of California’s middle. It’s bounded by coastal mountain ranges to the west and the high Sierra Nevada mountains to the east, in addition to mountains capping the north and south.

Draining these mountains are two main rivers: the Sacramento in the north and the San Joaquin in the south. The rivers run toward each other to meet near Stockton . . . so of course Stockton must be relatively low in elevation. Still, at only 13 feet it couldn’t be much lower or a lake would form and the water would never make it west to the ocean in San Francisco Bay.

Predictably, as we drove south of Stockton I watched our elevation climb. We were travelling upstream near the San Joaquin River and eventually near the Kern River toward Bakersfield whose elevation is 404 feet.

Home

Immediately upon arriving at our home near San Diego, our three kids jumped out of the RV and attacked the blueberry bushes. The blueberries hadn’t been picked for ten days while we’d been on the road so there were lots to eat. Our kids hadn’t eaten food right off of a plant for ten days either so they were eager to get some fresh stuff.

They migrated over to the apricot tree, then the cherry trees, then to the tomatoes and cucumbers.

In some fashion, our little yard with just a few plants of many different types seemed richer than those fields along the 99. Those fields were big, but they weren’t as impressive as they used to be. In fact, they seemed sterile and brittle.

My little garden looked tougher and more alive. I had arrived home more eager to feed my children from it, to grow more of my own.

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

I’m able to write because of reader contributions. Thank you, Supporters.

I enjoyed reading this. I’ve driven up and down the valley a few times myself, mostly on 5, but sometimes on 99. So much of the southern San Joaquin is like a desert not only for lack of water, but from an excess of various mineral salts left by too much chemical fertilizer over decades from what I’ve heard.

How big of a motorhome did you rent? What was your gas bill for the trip? I had a motorhome in the past and it was a fun way to travel and adventure, so I’m sure you had fun. I looked up some of the growers that had their names on the fruit boxes at Costco. Most were located along a big river up North. Did you stop at the CCPP? It is fantastic that you are raising your kids on fresh food from the yard. My mom always had a few tomato plants, but I was a teen and didn’t care about it. When I moved to San Diego, I planted my first garden in 1972 in the native dirt in my backyard. It looked like the plants in the “green acres” TV show. Bummed out, I discovered there were no organics in the native dirt. Knowledge is the key. The following year I grew corn higher than my roof and 3″ diameter radishes. Greg, you should write about your history and what started you growing food.

Hi Richard,

The RV we rented for this trip was the biggest we ever have at 32 feet. The gas bill was huge, as you might imagine. Still better than flying though, in every way except speed.

Funny thing, when we crossed the border from Oregon into California the price of gas immediately jumped by $1.20 per gallon but the road quality dropped precipitously. Roads were so bumpy that the passenger window rattled loose and I had to make an emergency stop on the shoulder of the 15 near Temecula before it flew off.

My mom also always had a vegetable garden in the backyard, and I also paid it no attention when I was a teenager. Nevertheless, when I started growing things I was able to recall memories of the different crops in her gardens so I suspect it had more of an influence on me than I knew.

A history of how I came to growing food has always felt self-indulgent so I’ve never considered writing it, but maybe if I choose the right parts to tell it could be useful.

Such insightful observations Greg. That last paragraph is beautiful!

Thanks for sharing your observations, all very interesting and sad. The largest citrus growers also owning the pesticide company reminded me of the last season of the TV series, Goliath. He took on the almond growers, who owned everything. Interesting about bees and seedless mandarins. Thanks for your feedback on our tangerines last year. We took off as many dead fruit as we could and it is producing like crazy. The smaller fruit don’t have too many seeds.

That was an awesome article. We drove that route just a few weeks ago as well. Every time I go that way I wish there were signs along the road telling us what is growing in the fields and orchards. Now I know thanks to you! I love your family-garden reunion too. When we got a few weeks ago, we bee-lined to the raspberries and blackberries and stuffed our faces!

Hi Jessie,

I always wish for the same, that there were signs showing what is growing in every field. I can identify most not all.

The Kawana Club used to post blue signs on the fences along the 99. Some are still there. Maybe it’s time we ask them to do it again. Thanks for visiting our home! We live between Fresno and Bakersfield.

This article substantiates all my son has shared with me about the misuse of our land. He gets very upset.

How much time do we have left?

Do we have to rise up in the streets to change the “politics” of agriculture? Maybe so!!

Hard thing is the world depends on the agriculture of central California

WOW! That is such good information. Thank you so much.

Hi Greg, I’m reading conflicting information about the tap root on an avocado tree, some say the roots only go down about a foot, others say it has a tap root that goes down about 3 ft, and if it hits clay with no drainage, your tree will die, I can’t think of anyone else that would know the real facts other than you! Thank you, Cameron