In 1984, a new avocado variety was patented by the University of California and released to growers. It was called Gwen, and it showed great promise.

Gwen was estimated to produce approximately double the amount of fruit per acre compared to Hass, the standard variety. More than that, most people thought it tasted as good or better. (See, “Three New Patented Avocados.”)

As if that weren’t enough, Gwen trees were also smaller than Hass, which made the fruit easier to pick, plus they produced more fruit at a younger age, meaning you would get a quicker return on your planting investment. (See, “The New Gwen and Whitsell Avocados.”)

Before I had my own experiences with growing and eating Gwen, I read about these details of the variety in the California Avocado Society Yearbooks, in articles in the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere, and I was attracted.

I was also mystified, because after 1994 Gwen essentially vanished from the written record. Tom Markle, an avocado farmer in Escondido and a former president of the California Avocado Society, wrote in the 1994 Yearbook an article titled, “Gwen Variety Update,” and it was the final word on Gwen that I know of. Markle wrote that he had had “mixed experiences growing the Gwen” but concluded the article by noting that his Gwen trees had at that time their best fruitset ever and he believed “that the Gwen variety can and should survive.”

Markle’s was a mixed message. It seemed that Gwen wasn’t perfect but neither had it shown serious flaws.

Nonetheless, Gwen did not survive, not commercially. Markle’s “Gwen Variety Update” turned out to be the Gwen variety’s obituary.

Why? What happened? I’ve been trying to understand this for the past 15 years, through eating Gwen fruit, growing the trees myself, and asking people who were eating the fruit and growing the trees before me, during Gwen’s commercial appearance and disappearance, about their take on the Gwen story.

I want to understand Gwen for its own sake. I find Gwen one of the best avocados to eat, and in my experience it is a fruitful tree with a long harvest season. So I want to know what went wrong with Gwen, but I also wonder if it has lessons for the future of other avocado varieties.

Three main problems

I’ve picked the brains of farmers, harvesters, handlers, breeders, and eaters. And the one thing I’ve learned is that there is no consensus, no single answer, as to what happened to Gwen. Nevertheless, I’ve noticed that three reasons for Gwen’s rise and fall are mentioned by most.

Green skin

Of the three most common reasons given, Gwen’s skin color tops the list. Always, people mention the green skin. Gwen has green skin, and the green skin is a problem.

In short, it’s because in the 1980s, when Gwen arrived, Hass had just become the dominant avocado variety and it had black skin when it was ripe. Consumers had gotten used to avocados turning black when ripe.

Gwen looks almost identical to Hass, except that its skin remains green. Even when ripe, Gwen is green. So consumers would be confused with some of their avocados turning black when ripe but others not. Would they let the Gwen sit on the counter until overripe because it was still green? This was the fear that handlers expressed. Handlers, also called packers, are those who buy fruit from farmers and then sell to retailers or other users.

Another way in which Gwen’s green skin was not desirable was that Florida avocado growers were the main competition for California growers at this time, and all of the avocados that came out of Florida were green. California could distinguish itself with black Hass fruit, as Hass does not grow well in Florida.

The peel of Hass turning black as it ripens has one more advantage, which is to hide blemishes. As avocados ripen, they often naturally get a few brown or black spots on their peels, similar to the spots that form on the peel of a ripe banana. Even if the flesh underneath is perfect, it doesn’t look pretty from the outside. Avocados like Hass that turn black as they ripen hide these spots; they just blend in with the overall darkening peel.

Moreover, commercial avocados are put through an ordeal to get from tree to store shelf or restaurant. They are handled many times, refrigerated, and ripened with ethylene gas. These trials ensure that a green-skinned avocado like Gwen will ripen with dark blotches. Hass will too, except the blotches are concealed by its dark skin. Out of sight, out of mind.

You’ll note that, while this is beneficial for handlers and retailers, it is of little benefit to consumers. Green-skinned avocados allow consumers to make more informed purchases. For example, look at the two Gwen avocados below. Which would you buy? You would buy the one on the left that has no stem-end rot, of course. But if these were Hass, you wouldn’t be able to see that the one on the right has stem-end rot.

Fruit drop

The second most common problem with Gwen that I’ve heard is that the trees drop fruit. One grower told me that the reputation of Gwen was that as soon as its fruit was ready for picking it would drop. Someone who worked on harvesting crews while Gwen was in its early years of expansion in commercial groves told me that he remembered being called to harvest a grove of Gwens only to arrive to find fruit all over the ground. This really spooked growers.

Further, this fruit drop issue couldn’t be counteracted by picking the avocados earlier. While Gwen avocados can taste good when harvested from a tree in Southern California in March, the fruit doesn’t look good as it ripens because its skin shrivels. In comparison, a Hass avocado picked in March will ripen without shriveling.

How was a grower to navigate this? While it was disheartening for farmers to see their avocados on the ground, buyers didn’t want avocados that shriveled when they ripened.

Young trees

Finally, some people have told me that young Gwen trees were hard to get going in the field. They didn’t grow as strongly out of the gate as compared to young Hass trees.

This was partly because Gwen was more precocious. Even newly planted, waist-high trees would bloom and try to set fruit. Some Gwen trees would bloom before even leaving the nursery. And sometimes they would bloom so intensely that they shed their leaves.

Growers liked the idea of a precocious tree, one that made a bunch of fruit in its early years so they could get an early return. However, the young Gwen trees seemed incapable of managing their own precocity.

Where the Gwen trees were grown without much stress, this wasn’t a problem. For example, at the University of California’s research station in Irvine, young Gwen trees performed wonderfully as the location was neither hot nor cold, the soil was a deep sandy loam, and the water was of good quality (at that time).

However, in less hospitable locations, under the watch of less attentive farmers, young Gwen trees sometimes struggled.

More about . . .

These were the most common reasons that I have encountered while seeking an explanation for Gwen’s disappearance from commerce. However, they don’t thoroughly satisfy me, and they beg for elaboration and context.

More about green skin

If consumers wanted only black-skinned Hass, then why did the University of California select the green-skinned Gwen for patenting in the first place? In fact, Gwen was one of three varieties that were patented and released in 1984, and all three were green. (The other two were Esther and Whitsell.)

This is partly explained by the fact that although Gwen was released in 1984, the variety was the product of an avocado breeding venture that began almost thirty years earlier, in 1956. That’s when Bob Bergh began searching for improved avocado varieties at the Citrus Experiment Station in Riverside, now the University of California at Riverside. And at that time, Hass was not the major commercial avocado variety in California. Fuerte was. And Fuerte is an avocado with green skin. (See, “Avocado Breeding in California.”)

Fuerte satisfied everyone, from grower to handler to eater, in most ways. The fruit was about the ideal size, had a long harvest season, and tasted excellent. The main complaint came from growers, and it was that Fuerte trees did not bear enough fruit consistently.

Therefore, Bergh wrote in 1961 that the aim of his program could be stated in an oversimplified way as to be looking for: “A Fuerte that bears dependably.” (See, “Breeding Avocados at C.R.C.”)

During the 1960s and 1970s, Hass was grown more and more in California and elsewhere. It was a variety that clearly had great potential, as it was delicious and it fruited relatively consistently. Yet it was unclear how popular Hass could become because of its skin. As an Israeli grower wrote in 1965, “The Hass carries well to distant markets and tops even the Fuerte in quality, but its well known drawback is its black and warty surface.” (See, “The Avocado in Israel.”)

Consumers were beginning to accept Hass fruit due to its eating quality, but they didn’t appreciate its appearance. What was unappealing about black skin on an avocado? Black is the color of rotten spots on an avocado. (See the photo of the Gwen with stem-end rot above, for example.)

But what if you could find a variety that bore consistently like Hass and had great eating quality, but had green skin like Fuerte? Seems the best of both worlds. Eureka: Gwen fruits even more than Hass, is great eating, and is green like Fuerte!

This was the historical context in which Bob Bergh selected, patented, and released Gwen to growers.

Unfortunately, the desires of handlers were changing at the very moment of Gwen’s release. In 1985, David Freistadt, then president of Calavo (a large avocado handler), wrote, “. . . the industry has spent millions of dollars in an attempt to teach consumers that the Hass avocado turns dark — even black — as it reaches edibility. If we suddenly begin to market an avocado resembling the Hass but never turning dark, will our educated consumers let the avocado rot as they await its darkening as they have finally been taught? Or how much will we need to spend to re-educate without confusing?” (See, “An Appraisal of Gwen and Whitsell.”)

Many handlers had become so accepting of Hass that they were now interested in only Hass. “A monoculture is a marketer’s dream,” I heard one avocado handler say.

Gwen had been the right color when Bob Bergh began observing it (the seed was planted in 1963), but by the time he ushered it through the patent process and released it for commercial growing in the 1980s, it had become the wrong color. Through no fault of Bergh’s, Gwen was dead on arrival.

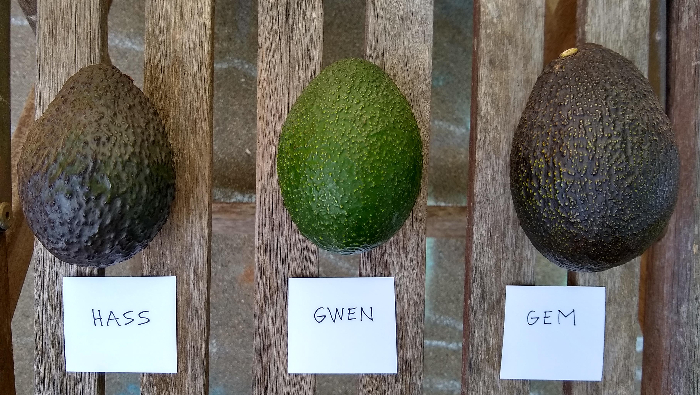

And the University of California breeding program has not patented and released a single other green-skinned avocado since Gwen. Lamb, Sir-Prize, Harvest, GEM, Luna – they are all black.

More about fruit drop

Over time it was discovered that Gwen’s habit of dropping fruit disappeared as trees matured. One grower told me the phenomenon ended after trees had been in the ground for more than three years. Another grower told me it took more like five years for the fruit drop to stop.

Moreover, this behavior of young trees dropping fruit isn’t unique to Gwen. Lamb, a progeny of Gwen, acts the same way. Reed and Edranol do too. They drop fruit when nearing maturity while the trees are young but largely grow out of the pattern after a few years.

I know some Gwen trees that are decades old, and while they do drop a few fruit in the spring just before harvest time, the amount of drop is comparable to most other varieties.

Seeing fruit on the ground is never pleasing, but as one grower put it, “You have to count what’s still on the tree, not what’s on the ground.” And the ultimate yield on mature Gwen trees that I know are very high, at least as high as Hass. The tree in the photo above, for example, yielded approximately 1,000 avocados this past summer. I know because I harvested and counted them.

Nevertheless, I can understand the shock that it would cause a grower who had recently planted a few hundred Gwen trees to see a large portion of their first crops being shed and rotting on the ground, not knowing that it was only a juvenile problem.

More about young trees

Hass is usually an easier tree to grow from the start, it’s true. More precocious varieties like Gwen require more attention; they require better irrigation, possibly better fertilization, staking and training, and sunburn protection. Fruit might need to be thinned from a young Gwen tree. One has to protect the tree from its inclination to fruit itself into damage at a young age.

But Gwen is by no means the first variety to require such attention. The old variety Lyon was known to bear “so precociously and so heavily that the tree is severely stunted and sometimes killed outright.” (See, “Breeding Avocados at C.R.C.”) And Pinkerton is similarly capable of stunting itself through fruiting too heavily too early.

Today we have GEM, another seedling of Gwen, which can also bloom so intensely at a young age that it sheds all of its leaves.

This characteristic of young Gwens and GEMs is a real challenge, and it seems inextricably linked to the variety’s precocity. Getting the trees through their first few years requires more care than less precocious varieties.

But here is the blunt take on this topic from Bob Bergh: ”If you can’t ensure good tree care, you probably shouldn’t be growing Gwens. (But then again, if you can’t ensure good tree care, should you be growing avocados?)”

In the end

Therefore, in my understanding, Gwen mainly failed commercially because it is green. Handlers preferred black avocados, Hass specifically.

To a lesser extent, Gwen was not embraced by more growers because young trees were trickier to grow and dropped some fruit, at least in some locations for some growers.

Were Gwen’s chances further hurt because of a hasty introduction into commerce? This idea was suggested to me by someone who worked within the industry at the time of Gwen’s release. What if the variety hadn’t been released until it had been trialed for longer in more varied growing situations (outside of university facilities)? Then Gwen’s fruit drop issue would have been seen to fade with tree age, the challenge of establishing young trees would have been no surprise. Growers could have started their Gwen plantings with more education, and therefore perhaps more success amid realistic expectations.

Maybe. But Gwen is still green.

So Gwen is primarily a backyard variety today. But it is a prized backyard variety. Everyone I know with Gwen plus other varieties in their yard or grove considers Gwen one of their favorites.

Sadly, Bob Bergh passed away last year. Gray Martin, who worked with Bergh for many years as his assistant, told me that Gwen was Bergh’s favorite variety until the very end. Gray added with humor, “Now, it was named after his wife . . .”

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

Hey! Why aren’t there any ads on this website? Because of your support!

Can one still buy a Gwen tree or a Gwen scion? I’ve started a couple of trees from seed with the intention of grafting. Any suggestions as to where I could find Gwens?

Hi Judy,

Gwen trees can be found here and there. I saw a few at Plant Depot in San Juan Capistrano a couple weeks ago, and I bought one some years back from Atkins in Fallbrook. Subtropica in Fallbrook also has them sometimes. Four Winds Growers sometimes carries Gwen trees.

As for budwood, your local chapter of California Rare Fruit Growers is the best source. Look out for their scion exchange, usually held in January or February. See here for more sources: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/where-to-get-avocado-scion-wood/

If you have no luck, let me know and I’ll get some Gwen budwood to you.

I bought my Gwen avocado tress at Maddock’s Nursery in Fallbrook. It’s a great variety.

Thanks, Sam. I hadn’t known Maddock was making Gwen trees. Maddock is an excellent nursery.

Hi Sam,

What time of the year were you able to find Gwen at Maddock? I’ve gotten trees from them before both at their main office and the growing grounds but haven’t seen Gwen.

Thanks,

Jes

Hi Jess,

I picked my Gwen from them last January. I would call them first to see if they have them. They have good trees and reasonably priced too.

I saw them in 5G at Walter Andersen – Poway last weekend.

I can understand why growers are looking for more production, but Hass is a great producer compared to my other varieties. Not being a commercial grower, my focus is on flavor, smooth texture without strings and shading from leaves.

Having grown up with Fuertes…and having sold them from the street corner as a kid for many years it’s *still* hard for me to accept the Hass. I so often find them stringy and badly bruised in the stores.

Also I grew up on a property with a couple dozen trees. Alas, my mom’s grove kept shrinking as water prices kept increasing. When I moved back here to provide her support in her final years only one remained (remains) and I have nurtured it back to a shaky health (there are termites). The lone avocado that survived is doing well and I’m praying it makes it to harvest. It will be the most expensive avocado…

What a bitter-sweet story, Debra. Thank you for sharing.

I ate my first Fuerte of the season yesterday, nearly a month earlier than usual. To my surprise, it tasted great. I picked it from the Fuerte tree in my mom’s yard.

Bob Bergh was my grandfather. I had the privilege of being around as he did his research, sampling many different varieties of avocados throughout my childhood. He would bring boxes and boxes full of avocados home, recording his research on graph paper at his kitchen table, using a teeny tiny nub of a pencil. Gwen was the by far the best avocado variety, and not just because it was named after Grandma. 🙂 This article answered some questions for me, brought me joy, and made me cry. Thank you.

What a wonderful note to receive, Heather. Thank you.

If I had a piece of that graph paper with your grandfather’s notes on it, I would frame it. I love the image of him recording his research that way.

Yesterday, I just removed avocados from one of my Gwen trees because even though it is only as tall as me it was carrying 35 pieces of fruit, which is too much for such a little guy. This tree is special to me, as I grew its rootstock from a Gwen seed. I grew a Gwen seed and then grafted Gwen on top. That’s how much I like Gwen, too.

Thanks for another great article. I bought a Gwen three years ago from Four Winds…and killed it, but before it totally expired took a scion and grafted to a seed. Last year the little wimpy tree had fruits, but took them off so it would grow, it has, now six feet tall with three leaders. Hope to get a few fruits in 2023. Wish the nurseries would carry less Hass, and more of these varities for backyard homegrowers.

Very cool, Frank. Which seed did you use as rootstock? I have a Gwen tree that I grafted onto a Gwen seed that I grew, and it is doing very well. Has its first fruit this year.

No idea, as I throw all our avo seeds as mulch under our trees, and the ones that push up I pot and then graft, so it was a Bacon, or Hass seed…Have never tasted Gwen, so really hoping for fruit. Thx for all the info.

Great article Greg. I also have been harvesting and eating my fuertes for a couple of weeks in Santa Ana, CA. Several weeks early. They are very large and of great quality. Family and neighbors are thrilled.

Thanks for the article. Do you have any experience or more information on the Harvest avocado variety? Do you know anyone who has it and can share info on it? Thanks in advance.

Wow, Thanks for a really great article. You’ve filled in some gaps for me. I recently found out that some older growers were giving away their Gwen avocados to a packer who was marketing them. That seems like such a sad place for the variety, after all of the effort that went into making them viable. I have also heard from growers and those in the associations that it was really the packers who made the “Gwen” not viable, because growers need an outlet for their fruit and many don’t market their own. They sell to packers like “Calavo”, “Index Fresh”, “Mission”. If the packers won’t take the variety, the growers won’t invest in it.

It seems to support what I have come to realize. Growing fruit commercially is really challenging, especially if you are growing newer varieties of things like avocados. Growing and caring for the trees is only one part of the challenge and that also depends on a support system that may not exist. Growers need large quantities of quality trees on rootstocks that can handle the stress of high chlorides in the water, diseases like Phytopthora in the soil, nematodes and other things that may attack the tree, so really specialized material. That takes skills that we have only a few nurseries managing. Climate Change is also a factor.

It’s funny about fruit drop, when we bought this property over a decade ago, the neighbor who had the adjoining property never bothered with his fruit drop. He just left it on the ground to rot, and he had plenty of fruit when he was ready to harvest in the summer, and that was mostly Hass. As the weather has gotten more extreme we’ve noticed the fruit quantity has been less, so the fruit drop matters more, the high temps of the summer burn more fruit now. I notice that Lamb Hass some years has a lot of fruit drop to so it can’t be just that one thing that scared people away from the Gwen.

The real work, for the farmer comes when you have conquered the growing and production side, when you have a crop to sell. Marketing takes creative thinking and taking risks, it is possible to build markets for newer varieties with special characteristics, like we have been doing with Pitahaya, but it is about building relationships and produce managers willing to be creative and take a chance with their customers, hoping they will want to purchase the newer items. There are so many places where this endeavor can get stopped, so it’s exciting when it works out. I hope we see more new varieties; I think that is the fun part. We are finding more and more outlets for the varieties that are not Hass. I agree with Frank, I’d like to see more varieties available for people to experiment with. Thanks again for your work.

Thank you for contributing all of this, Ellen. (For those who don’t know Ellen, she is a farmer of avocados, dragon fruit, and more, located in Valley Center, San Diego County.)

I was talking to someone who works for one of the large packers (handlers), and he echoed many of your ideas about new avocado varieties. He loves new varieties, but there are so many challenges at so many stages.

I have begun to think that packers are not the best medium through which to get new varieties to avocado eaters, not initially anyway. I think that direct marketing by farmers is a better way. My vision is that more farmers will direct market their avocados in the coming years, and this will build exposure and demand for new varieties. From here, the avocado growers and packers will respond to the demand. In a sense, it’s a bottom-up approach rather than a top-down approach.

In fact, I think this has already started happening. It has started in Southern California, and it has also spread to parts of Northern California. Next it will spread to neighboring states in the western U.S.

I don’t know how much farther it will reach. It might go farther in part because many people are moving out of California. I have many friends and relatives who have left and yet they grew up on avocados and know and want the good stuff. I ship good avocados to them sometimes. They might spread the demand.

As you alluded to, most farmers want to farm and not market. There’s a need for someone to show avocado farmers how to direct market using the internet, should they want to give it a shot. There’s also a need for more people to “indirectly” direct market avocados for farmers, especially small farmers, similar to what I have been doing for the past year. This way, avocado eaters get prime fruit of different varieties; eaters know the provenance of the avocados; and farmers gain a connection to the eaters in a way they never get when selling to a packinghouse.

It’s also possible that farmers will get more money for their fruit. I spoke with a farmer in Valley Center a couple weeks ago who said he has trouble getting good returns for his Reeds from the packers. Reeds! This is a crazy disconnect because every person who has eaten a Reed has fallen in love with it.

I have suggested to the California Avocado Society that they put together a seminar for growers about direct marketing. I hope they do this next year. Ellen, you should participate if they do!

I speak here from the perspective of an avocado enthusiast. I’m not a commercial grower, and I don’t know much about the marketing side of things. But I know avocados, I love to eat avocados, and I suspect that growers and eaters can be better connected and better satisfy each other’s desires. Frankly, I also fear that without innovation in this area, the commercial production of avocados in California is going to disappear before long.

Funny, until my own trees carry a good crop, I’ll keep buying from Spanish farmers who sell their avocados directly through the net. We’re pleased with the very good quality avocados we got from them. Bacon, Fuerte and Hass so far, mangos are also of good quality.

It just takes a couple of days to get them over to Portugal. A week or so to ripen on the counter and after that kept in the fridge for some weeks.

Our kids and friends asked for the links and now everybody is ordering avocados from farmers…

Thanks, Vasco. It’s great to hear that not only are Spanish farmers direct marketing their avocados but they are also pleasing sophisticated customers like you. I’d love to see the links to the farms you use too, if you don’t mind sharing.

I have been ordering from https://www.aguacatescereto.es. This week I ordered Hass. They started to sell them this week, kind of early but let see…

I have not seen fruit drop at all on gwen. They seem to hold on even into July and are at that point they are so ripe the fruit is getting on the dry and super dense side. Have not seen any drop. And if they hang any longer they will be too ripe.

There is a lot going on in Spain. A lot of direct sales, some produce their own avocados, others buy locally and sell online. All try to keep shipping within a couple of days so the fresh from the tree picked fruit arrives in good conditions.

Here https://www.campodebenamayor.es/comprar/frutas-tropicales/aguacate-de-malaga/ is where I buy half of my trees but the their avocados are of very good quality too.

My other trees come from https://www.fitoagricola.net/tienda-online/Catalog/listing/aguacates-42368/1

Sorry to get a little bit off-topic…

Greg, Nice job on this article. You did a lot of research and it shows. I appreciated all of the links to the California Avocado Society yearbook articles. Well done!

Recently, got a Gwen 5 Gal. from Louies Nursery (louiesnursery.com) Riverside. Also, they have most of the varieties for So.Cal.

I have a good sized Gwen tree and it produces very large round avocados. Larger than an orange not quite the size of a grapefruit. When they ripen they taste buttery smooth and delicious but trying to tell when they are ripe is difficult. When it starts getting soft like other avos, it feels ripe, but you cut it open and it’s hard and rubbery. If you let it go a little long the skin starts to shrivel, and it’s still rubbery. Not sure how to tell when is the best time to use.

Hi Justin,

What time of year are you harvesting these Gwens and where are you located?

Hi Greg

I’m in Murrieta and my Gwen is about 15 years old. It produced for the first 10 years, but no flowering or fruit the last 5 years. I have been negligent in fertilizing it, but the leaves look fine after it recovers from winter. I have a 6 year old Fuerte next to it that hasn’t flowered either. I’m going to try and girdle the Gwen and fertilize next spring. Maybe after so many years they lose their productivity? The flavor of the Gwen was excellent. Any recommendations are appreciated.

Thanks for your wonderful writings.

Hi Scott,

Very strange that the Gwen hasn’t flowered for five years. I doubt it’s related to age, as I know many Gwens that are decades old that produce well. You might try pruning it this winter to encourage it to grow some new, vigorous branches; those new branches should then flower the following winter/spring (2026). Sometimes mature avocado trees respond very well to this kind of rejuvenative pruning. See the discussion of “teenage wood” in my interview with John Schoustra here.

I work at a large government facility adjoining The City of Irvine. Approximately 40 years ago, this facility was working co-operatively with the University of California Agricultural Research Center, Irvine. Where they (UCARC) had planted several hundred “experimental” avocado varieties for research purposes on approximately 5 acres of the property. There are a few random unknown varieties on the facility still producing, but I believe most are experimental crosses. There is a favorite tree, 30+ feet tall, that produces amazing fruit, similar tasting to Gwen. Most deem it the best avocado they’ve tasted. If you are ever planning to be in the area, come visit and I’ll give you a tour.