I spotted this sign in a Starbucks the other day, featuring a coffee that is claimed to have Meyer lemon in its flavor profile, and I wondered how that would make Frank Meyer feel.

Initially, he might shake his head because he clearly requested that no plant be named after him. Then he might laugh that a little citrus tree that he easily found in China but which didn’t seem extremely significant at the time had become the plant most associated with him and most broadly enjoyed.

Discovery of the Meyer lemon

Meyer was on his first expedition as a plant explorer employed by the United States Department of Agriculture when he discovered the lemon that now bears his name. In 1905, he boarded a ship in San Francisco, arriving in China that September. Over the next three years, he explored that country in addition to parts of Korea, Manchuria, and Siberia, looking for plants that would be useful to people back in America.

Meyer collected scions of pears and peaches, jujubes and apricots. He also collected grasses and pines and roses and so much more. Near the end of the expedition, at Fengtai near Beijing, Meyer discovered a dwarf lemon tree that the Chinese used as a house plant. The Chinese used it for both its fruit and decoration. Meyer thought it could be similarly useful in American homes, perhaps also on commercial farms, so he included it in a shipment of plant materials back to the U.S.

Once received, some of Meyer’s plants were grown and tested at a USDA “Plant Introduction Garden” in Chico, California. Meyer visited Chico in 1915 to find that these dwarf lemons were producing a high yield there. It was also found that the tree was hardier than most lemons, withstanding temperatures as low as 22 degrees Fahrenheit.

This is why today the Meyer lemon is an extremely popular plant for home gardeners even in places too cold to grow most citrus outside through the winter. I’ve seen a number of Meyer lemons in homes in Oregon, for example. I would guess that the Meyer lemon is the most widely grown citrus tree in the world today.

Commercial farmers rarely grow it, however. It is too tender and juicy to ship well.

I don’t grow a Meyer lemon in my own yard, it so happens, but I often pick a few from friends’ and relatives’ trees because I enjoy adding the distinct, slightly sweet juice (for a lemon) to salsas.

Incidentally, citrus taxonomists don’t like calling the Meyer a lemon. They suspect that the tree is actually a cross between a lemon and sweet orange — so not a true lemon.

(For more, see the page for the Meyer lemon at UC Riverside’s Citrus Variety Collection website.)

Frank Meyer wasn’t his real name

I knew little more than the baristas in Starbucks about the history of the Meyer lemon before reading Isabel Shipley Cunningham’s book, Frank N. Meyer: Plant Hunter in Asia. I certainly didn’t know that Frank Meyer wasn’t exactly his real name. It turns out that Meyer was born in 1875 in the Netherlands as Frans Meijer.

He spent his youth working in gardens and nurseries, and exploring much of Europe on foot using a map and compass, until he saved enough money for a voyage to America in 1901.

Once in the U.S. he began to call himself Frank Meyer, and he soon found work in a USDA greenhouse in Washington D.C.

From the East Coast he moved to the West Coast, next finding work at a USDA station in Santa Ana in Southern California. “Here a boy can eat as many walnuts, peaches, figs, or watermelons as he wants. The fruit rots on the trees, so plentiful is the supply,” he reported to a friend.

But Meyer wasn’t built to stick around in one place for long. “A man is constantly wishing and longing for farther off and unseen places,” he wrote to the same friend. “Why do we have that desire?”

He wandered up to Montecito, near Santa Barbara, where he became the head gardener of a commercial nursery. But soon again his feet began to itch. Before leaving, he explained to another friend: “I long for a bit more change in the weather. This is a splendid climate for old and sick people, but not for a normal, healthy person. I think sometimes with pleasure how a snowstorm would do me good.”

Yet he didn’t head north for long. He spent a little time in the San Francisco Bay area only to soon wander south through Mexico, mostly on foot. It took him two weeks to walk from San Blas to Guadalajara, all the while discovering fruits and flowers that were new to him, some of which he collected seeds from and sent up to a friend in California. As expected, he found the heat oppressive though.

When he returned to the U.S., his savings had been exhausted too. He found work at a botanical garden in Saint Louis, Missouri until, in 1905, a dream job offer appeared: Explore China for the United States Department of Agriculture.

He wrote to a friend that he now regarded the United States as his native land, and he wrote to his parents back in Holland, “I can hardly believe I got such a beautiful job.”

And so in 1905 he boarded a ship in San Francisco to head across the Pacific. He felt “very happy at the thought of giving people many new plants and fruits from China.”

Plant hunter in Asia

From 1905 until 1918, Meyer took four lengthy expeditions through various parts of Asia, from China and Japan in the east to Russia in the west. The expeditions were interspersed with brief visits to the U.S. to visit farmers, researchers, and directors of botanical gardens to inquire about what plants he could hunt for them in his next expedition.

So in short, Meyer spent more than a decade homeless but very much employed, walking over mountains and through inclement weather, navigating new languages and cultures and laws, submitting materials and reports to the government, while eating and sleeping strangely.

Have you ever lived in even a similar way? Can you imagine doing so for years on end? I don’t know that I’ve ever read of a tougher man than Meyer.

“Sometimes I am surprised at myself because I get so easily through so many difficulties,” Meyer wrote to his mother in a letter from China.

As far as physical courage and stamina went, Meyer was peerless. His guides, interpreters, and carters often quit on him because they couldn’t keep up, and he had a hard time finding assistants in the first place because of the remote and lawless regions he intended to explore for plants.

One Chinese named Chow-hai Ting came close, accompanying Meyer as his interpreter on at least part of all his expeditions.

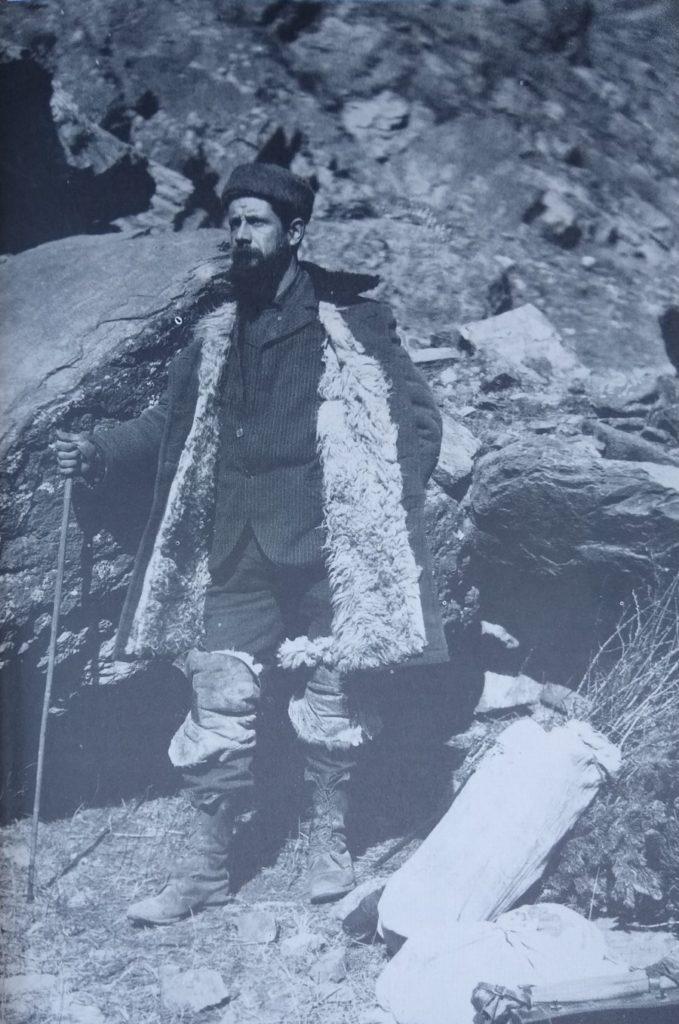

But the only assistant who never quit on Meyer was “a young Hollander who is out here on his own” named Johannis de Leuw. Together they dealt with bands of robbers and even once fought off Chinese soldiers who thought they were smuggling opium. Meyer wrote that they fought “with our fists, a walking-stick,” and the rifle shown below.

Meyer handled well the frigid weather, walking tens of miles daily, sleeping on hard brick beds infested by bedbugs and lice. But certain social circumstances were more challenging.

During one expedition, Meyer approached Asia from the west, entering through Russia where he found the impenetrable bureaucracy and corruption intolerable. Nevertheless, from Russian Turkestan, Meyer sent home wheat, millet, apricots, and more.

Meyer’s physical steel was an odd couple with his honest and sensitive spirit. When the treasurers at the USDA quibbled with some of his expense accounts, he was offended and eventually began paying for some legitimate costs required to execute his missions with his own salary.

Especially during later expeditions, Meyer acknowledged in letters home that he was lonely. But often, he followed such acknowledgements with reassurance that it was just a passing mood. However, his final expedition was undertaken reluctantly. He had fallen ill before leaving the U.S. and had written to a friend who also worked for the USDA that he was feeling older and, “There are times that my loneliness may destroy me.”

World War I broke out in Europe while Meyer was exploring for plants in Asia, and it broke his heart. When the United States later joined, his spirit was lowered so far that he could neither eat nor sleep. He wrote, “Is it strange that a man gets very tired? And more so now that my adopted country has seen fit to join in this monstrous war.”

During this final expedition, Meyer penciled notes on tattered envelopes that he titled, “Proposed Resignation.” Parts of Meyer’s notes read:

“Not feeling as well as formerly — sleeplessness — less energy”

“Paralyzing effect of this terrible everlasting war”

“Loneliness of life and very few congenial people to associate with”

“So much squalor and dirt in China”

“No garden to study the plants one has collected”

“I should return to Washington some time in June, 1918.”

“I will probably resign from the service on July 1, 1918.”

“It may seem strange that a person of my age, 41, should already become weary, but . . .”

It doesn’t seem strange to me at all, and for reasons beyond those related to his peripatetic lifestyle. Sometimes Meyer’s entire shipments of plants back to the U.S. arrived dead, while other times they weren’t grown or cared for at the USDA facilities in the way he hoped. This nagged at Meyer’s sense of purpose. One thing that got him through the physical difficulties and loneliness was the sense that his efforts were a great and appreciated contribution to the people of America.

He soon wrote to David Fairchild, his boss at the USDA, “I wish I could talk to you. I often think the life I am leading here is perhaps not the thing I ought to continue much longer.” And Meyer suggested to Fairchild that a younger explorer named Wilson Popenoe might be able to come over and continue the exploration of southern China.

Nevertheless, doggedly determined, Meyer continued collecting pear seeds, Ichang lemons, kiwi, and more.

On May 31, 1918, Meyer boarded a riverboat on the Yangtze headed to Shanghai. Most foreigners traveled first class, but as usual Meyer chose less expensive accomodations.

Prior to boarding though, Meyer had noted that he felt “stomach trouble accompanied by vomiting” and so he had delayed his departure for three days. Once on the boat, he seemed to feel somewhat better, as he ate a normal dinner the following evening, on June 1, but close to midnight Meyer was seen leaving his cabin, and then just before midnight the cabin boy reported to the captain that he could not find Mr. Meyer.

A search of the small steamer turned up nothing. A few days later, a Chinese boatman found a swollen body on the river that was eventually identified as Meyer by a U.S. State Department official.

Had Meyer jumped overboard? Had he fallen over the rail while vomitting? Had he been pushed? Had something else entirely occurred that night?

Thank you, Frank Meyer

In such a short life, Meyer worked himself to the bone and accomplished more than most. He sent thousands of pieces of plants back to the United States from Asia, and a couple have personal significance to me.

Meyer introduced Pistacia chinensis, the Chinese pistache tree. My family spends many hours under the wonderful shade of a Chinese pistache tree in our backyard, and I can’t help but take pictures of its fiery colors every fall.

And Meyer collected and sent home thousands of seeds and scions from different peaches he found. One was called the northern wild peach (Prunus davidiana) and it was found to need less water and be resistant to a pest that lives in the soil called root-knot nematodes. Some of the seedlings of Meyer’s collected northern wild peaches were grown by John Weinberger of the USDA. One of Weinberger’s seedlings was eventually released as the Nemaguard peach in 1961, and it is still one of the most common rootstocks used for many kinds of stone fruit, including my own Snow Queen nectarine tree.

If you look around your yard, you’ll also probably find plants that can be traced back to those Meyer worked so hard to find and send here. There are many more beyond the Meyer lemon.

From Cunningham’s biography: “British authors have said that [Frank Meyer’s] name should be a household word in America and that American farmers should celebrate an annual Meyer festival in grateful remembrance of his work in Asia. Yet few Americans are aware of their debt to the man . . .”

For more citrus stories, check out my post “Saving the Parent Washington Navel orange tree.”

All of my Yard Posts are listed here

Great post, Greg.

I see that you have a Gardening Books post. Wondering if you would want to put together a general Botany Books post? I’m always looking for engaging botany-related books. A few that come to mind: The Orchid Thief, The Martian (ok, mostly not botany related – but the potato farming was great), The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World.

Anyway, keep up the great work.

Thanks,

Evan

Hi Evan,

I love that idea. I’ve been reading biographies of plant explorers lately as a friend with a collection has been lending to me.

The Humboldt book looks very fun. Thanks for the suggestion.

Hi, Greg:

I LOVE Meyer lemons, and rarely use anything else. Thank you for all the wonderful history on them; I enjoyed it immensely!! Several years ago I purchased at a local nursery a dwarf Meyer lemon tree to grow in a large container pot. Several times I’ve had profuse blossoming, but only 1 lemon has matured, and that did not ripen properly. Not sure what my problem is, but it is beautiful to look at, and smell the citrus when it blossoms.

Thanks for your compassionate writing on this and other subjects! I am just starting to plan a food garden in Fullerton and am very grateful for your advice. Somehow Meyer’s story reminds me of the novel, “Please Look After Mom,” which my mother read and admired not long before she died.

Hi Gregg, dani here in Indonesia, can you help me identify an avocado tree based on their leaves. I’ve a tree which had a large leaf, really large indeed, i don’t find anywhere on the internet, website, whatever… dunno what kind of cultivar this is, what its name, etc…. I bought this tree from a nursery in Indonesia, apparently they mislabel it often, so I doubt that this tree is a Yamagata cultivar

Great article Greg. I have a Meyer lemon tree in my back yard next to a eureka. We are a half mile off the ocean in Northern California. The Meyer lemons are juicy and prolific. The eureka is thick skinned and lacking in juice. Meyers are definitely the way to go in cooler coastal areas! I recently planted a Lisbon lemon and a kaffir/makrut lime. I’m sure in a few years they will also be large.

Question for you. Do these citrus trees take a year off like an avocado tree? I’ve noticed over the last couple of years that they seem to cycle. Luckily the Meyer and the eureka seem to be on opposite cycles.

I noticed that virtually all the citrus in my yard had a horrible bloom last year, thus virtually no fruit this year. Friends of mine in San Diego county have said the same.

Weird, Bob. My citrus had normal bloom and fruitset — nothing great, nothing poor. I have noticed some citrus trees in other yards with little fruit, but I’m not sure if those trees usually have more. I’ll ask about it.

By the way, I have a boysenberry plant for you.

It’s been hit and miss . The Cara Cara has a few as does the satsuma and Meyer. My 4 in one grapefruit and Moro are pretty light. I’m hoping it was just an off year. Thank you on the boysenberry.

Hi Dan,

I haven’t noticed lemons bearing much more or less in alternate years. They seem fairly consistent around here. But maybe there’s something different about your environment that causes that.

Really enjoyed the read. Thanks! So do we blame him for citrus greening disease? Joking of course.

Thanks for posting this wonderful travel history of Frank Meyer and the Meyer Lemon. I think I may find a place in the yard for a Meyer Lemon tree. I do like the flavor.

As always, your writing is exceptional, Greg. I have a new respect for the Meyer lemon.

I am growing a Meyer’s lemon tree. Thank you for sharing some of its history.

Interesting story. Seems these “explorers” of nature were tough and determined. His ability to travel into unknown areas with little protection and provision reminds a bit of John Muir also from another country (South Africa) Another little known explorer/researcher, Jaime DeAnjulo, who came here from Spain and lived with Native American tribes to learn the language and customs. We owe much of what we can enjoy today because of those determined explorers. It is good we know more about them.

I live in Chico where the Chinese Pistche line the street in front of my shop and many yards have the prolific Meyer lemons. I am currently helping a start up here that is introducing a Meyer lemon bitters. Franck’s life was one great adventure and my mind wonders to the time the world was that place.

My mother, an etnic Swede from Finland, who ended up in Sacramento, California, with my Hungarian father, who was a professor at CSUS, grew Meyer lemons, along with several other citrus trees, all around their 1/3 acre lot as both bushes and trees. She used them in her tea every morning and always marveled at being able to do so – so different from growing up in Helsinki! She made sure that the lemons hung on the trees and bushes all year-round so she could revel in their beauty and also have a constant supply.

I now live in Lexington, Kentucky, where I have a Meyer lemon bush in her honor which must come in every winter and go out every spring into the backyard. Unfortunately, it doesn’t produce many lemons, but I cherish the ones it does produce.

I was absolutely fascinated to read this story of Frank Meyer. Thank you so much for writing it.