We were on the corner of Arlington and Magnolia in Riverside, looking at some citrus trees surrounded by a wrought-iron fence. It was 2012, I was with a group of Master Gardener trainees, and our guide started telling us the story of one of the trees. The tree was, at the time, 139 years old.

A woman living in Riverside named Eliza Tibbets knew someone at the United States Department of Agriculture in Washington D.C. and convinced him to ship her some orange trees. The trees had been grown in a USDA greenhouse and created from buds of trees imported from Brazil.

Mrs. Tibbets and her husband Luther rode in a horse-drawn, buckboard wagon to Los Angeles to fetch the trees. This was in 1873.

Three trees had been shipped from Washington, but only two survived to be planted on the Tibbets homestead. It is said that Eliza irrigated the young orange trees with dishwater. Soon after they began to fruit, their value became apparent.

“This was a citrus unlike any of the seedy oranges that existed at the time from seedling trees. The navel orange was larger, contained no seed, had a superb sweetness and flavor, peeled easily, had a bright orange color and matured for the winter and spring months especially around Christmas and New Year period,” wrote Chester Roistacher, a retired citrus virologist at the University of California, Riverside, about the fruit that came from the new Tibbets orange trees.

Our guide that day was not Roistacher but Gary Bender, a University of California farm advisor (now emeritus). Bender told us that these Tibbets navel orange trees soon became so desirable that the Tibbetses made a nice income selling buds to people who wanted to propagate a tree of their own.

To protect their assets, the Tibbetses erected a barbed wire fence around the trees. (See a photo of this from around the year 1878.)

Over time, the surrounding community of Riverside was enriched through growing vast groves of these new Washington navel orange trees, so named because they came from Brazil via the USDA in Washington, D.C. You could say that the city of Riverside was grown by selling Washington navel oranges. Riverside became the center of citrus growing in California, with the University of California’s Citrus Experiment Station being established there in 1907.

Did you grow up in Southern California like I did? Do you have the same memories as I do of eating Washington navel oranges throughout your youth? My grandparents had two of the trees in their yard in Glendora. And I recall picking navel oranges from the remnant groves throughout town when I was a kid in the 1980s and early 90s.

I liked navel oranges so much that in high school I ate seven in one day, which ended with some time on the toilet.

They were just oranges back then though. I had no idea why they were called Washington navels let alone the fact that their center of commercial origin was in nearby Riverside.

But there I was in 2012 looking at the oldest Washington navel orange tree in the world. Gary Bender pointed to the trunk of the tree. The base of the trunk had what looked like flying buttress supports.

Bender explained that the tree was still alive because grafts had been attached to the trunk through a method called inarching. I later learned the details, which were that a disease called gummosis had attacked this tree and its sister tree, killing its sister tree in 1922. So before this tree succumbed, citrus experts attempted to save it by grafting onto it a variety of new rootstocks — “seedlings of sweet orange, rough lemon and sour orange” — the hope being that at least some of the new rootstocks would be resistant to the gummosis disease that is caused by Phytophthora fungi.

The inarch grafting worked, to a point. “In 1951, it was noted that some of the original inarches showed lesions of Phytophthora. Therefore, in that same year, a second inarching was done using three seedlings of Troyer citrange and one of trifoliate orange.” The Parent Washington Navel orange tree was saved again in this way, so wrote Roistacher.

About two years ago, in February 2019, I visited the Parent Washington Navel orange tree again. I was by myself this time. I just wanted to see how she was doing.

The intersection of Arlington and Magnolia is a busy one. There are apartments on one side, a 7-Eleven and a Baskin Robbins on another. Cars zoomed past and I wondered how many of their drivers knew why there were citrus trees behind a fence here.

I came expecting there to be some kind of protection over the trees but found none.

There’s yet another disease in town, don’t you know? It goes by a few names: citrus greening, huanglongbing, or most commonly HLB. The disease is caused by a bacterium that is spread by a tiny insect called the Asian citrus psyllid, or ACP. This insect feeds on citrus leaves, and if it is carrying the bacteria then the bacteria can enter into the citrus tree. There is no cure for the HLB disease; infected trees decline in health and die.

(More about ACP and HLB here and here.)

So I expected there to be some kind of tent over the Parent Washington Navel orange tree to protect it from the Asian citrus psyllids. These insects are now all over Southern California. An inspector with the California Department of Food and Agriculture visited my yard in San Diego County a handful of years ago and showed them to me on the leaves of my own citrus trees. (They’re so small that you’d never notice them unless you knew what you were looking for.)

Moreover, citrus trees infected with the HLB disease had already been found in Riverside starting back in 2017.

Here I was two years later, in 2019, at this tree designated Historical Landmark Number 20

. . . at this tree called the “most valuable fruit introduction yet made by the USDA”

. . . and it was being left to its own defenses — against a fatal, incurable disease that is known to be floating around the neighborhood?

A few months later the protection appeared. In April of 2019, up went a white tent over the tree. Then in June, a stronger structure was erected.

I hope the protective structure works. That is, I hope that the efforts of humans to save this tree once again works. (Many other methods of fighting HLB besides protective structures are also being researched and used, by the way.)

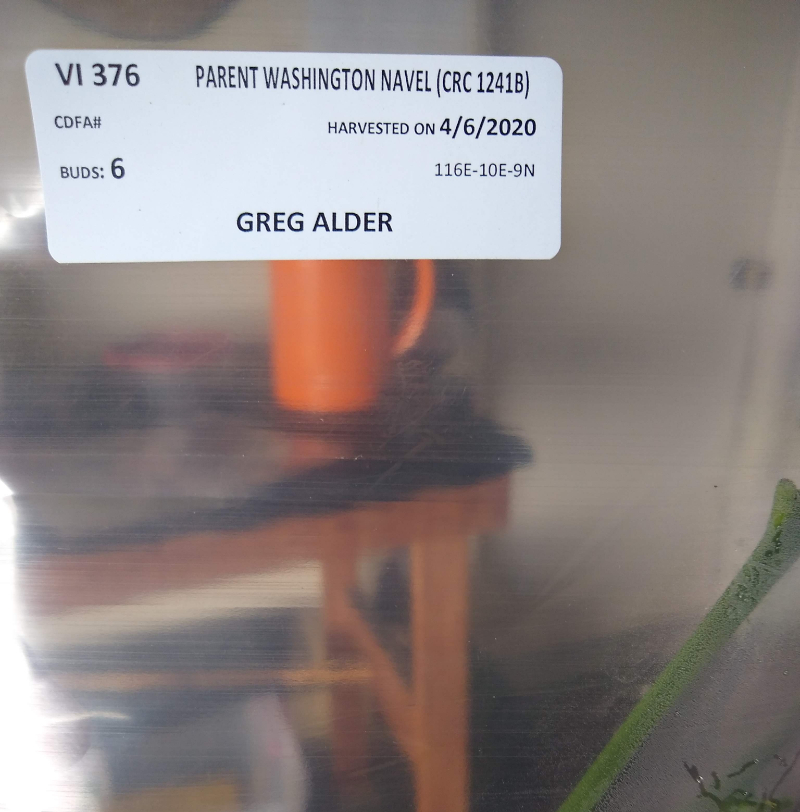

Regardless, I came home with the desire to possess my own piece of this tree and part of this history. So I ordered a few budsticks of the Parent Washington Navel orange from the Citrus Clonal Protection Program.

And I grafted them onto some other types of orange trees in my yard.

Check out this slideshow of the history of the Parent Washington Navel orange tree made by Chester Roistacher.

Incidentally, Roistacher did work to create the “Improved” Meyer lemon. Frank Meyer introduced this tree to America about a century ago. Check out my post, “Meet Frank Meyer, of the Meyer Lemon.”

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

thanks for this insightful article. i’ll look to get some scions also from CCPP and if they take it’ll be a good story to tell people too!

the inarching method was interesting. could it be done for let’s say older avocado trees? i’ll have to research it some more and see if i can bring some vigor and growth to some older trees.

Hi Johnny,

That’s a great question. I know that it has been tried on avocados. See this article from 1964: http://www.avocadosource.com/CAS_Yearbooks/CAS_48_1964/CAS_1964_PG_72-77.pdf

But I don’t know for sure why it isn’t commonly done today. Maybe partly because new trees on clonal rootstocks are widely available now. And maybe partly because inarching seedlings (as opposed to cuttings/clones) was found to be the most successful method in the experiment linked to above (and seedlings have variable characteristics).

Also see this article that refers to some success with inarching in Israel for problems with chlorosis, salinity, and low productivity: http://www.avocadosource.com/Journals/HorticulturalReviews/HortRev_1995_PG_381-429.pdf

If you give it a shot, tell us how it goes.

Thank you for this interesting article. I grew up in Riverside, graduating from Poly High School in 1982 (our school colors were green and orange!). There used to be orange groves everywhere, and the smell of the blossoms was always around. It was so different back then.

My grandfather and his brothers owned Evans brothers packing house in Riverside in the 1940s. I grew up with boxes of oranges and never knew anything but fresh squeezed orange juice. Too bad my family did not keep the land… most of his orange groves were sold in the 1960s.

Thank you for the article. Taking the bus to Riverside Community College vía Magnolia I passed the tree daily and wondered at the white tent, thanks for the explanation!

Great article. Can you tell us more about HLB and what’s being done to stop it? My understanding is that if it gets a foothold we’ll no longer have citrus in California. I’ve heard horror stories about the groves in Florida

Hi Bob,

Good to hear from you. Thanks. HLB is being fought on so many fronts that it’s hard to keep up with. Researchers are looking into resistant cultivars, resistant rootstocks, genetic modification of cultivars and rootstocks, antibiotics, pesticide sprays, protective tree covers, flower patches that increase populations of beneficial insects like hover flies, and on and on.

Some interesting recent developments include a peptide that a U.C. Riverside researcher found to effectively kill the HLB-causing bacterium: https://news.ucr.edu/articles/2020/07/07/uc-riverside-discovers-first-effective-treatment-citrus-destroying-disease

And a possible HLB-tolerant rootstock: https://citrusindustry.net/2020/07/20/rootstock-offers-high-hopes-for-hlb-tolerance-maybe-resistance/

California is in a position to save itself from this disease in a way that Florida (and Brazil) did not. I’m optimistic. There are innumerable smart people working on this, and they have millions of private industry and government dollars driving them. But even if they fail, we’ll still have citrus; however, we won’t have century-old trees out in the open like the Parent Washington Navel orange tree was.

My understanding is that citrus trees in much of Asia (where HLB comes from and has been known for nearly a hundred years) typically only live for a decade or two before they’re infected and killed by the disease. For example, see here: https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=10510

Even for us home growers, there are many things we can do to help. See this page: http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn74155.html

I’ll mention just a couple here. One is to try to keep the Asian citrus psyllid populations low. There are many insects, parasites, birds, and spiders that eat or kill the psyllids. So not using pesticides that harm these predators helps.

Also, Argentine ants protect and proliferate the psyllids. Therefore, killing Argentine ants can reduce the Asian citrus psyllid population. I’ll soon write a post on my experiences killing Argentine ants, but for now I’ll just say that I’ve been getting better results with KM AntPro than anything else I’ve tried: https://www.epestcontrol.com/pest-products/177-3956-km-ant-pro-liquid-ant-bait-kit.html?preadd=action&key=KMANTPROKIT

Wow! This blog post contains exactly the kind of wonderful, informative, and little-known information that I look for as I scan the internet for something to read! Glad I found The Yard Posts and looking forward to reading existing posts and keeping an eye out for new ones! Thank you, your humor and expertise are much appreciated!

Thanks, Gene! I really appreciate the encouragement.

Hi Greg –

I’m redesigning my yard, and am dreaming of growing a single huge orange tree in the the most prime location. I’m located in Carlsbad, and see tons of orange trees growing in my area. Problem is that the oranges grown on these trees taste “watery” and bland to me. Nothing like the oranges I had as a kid growing up in Orange County (we had an orange tree in our backyard that I adored).

I recently bought a bag of oranges from California Citrus State Historic Park (Riverside), and a flood of memories poured in… that’s the taste I miss!!! I’ve been researching as much as I can about the trees, rootstock, etc. trying to figure out whether it might be possible to have a beautiful tree in my yard that ALSO produces amazing oranges. I currently have little knowledge about growing fruit trees, but I do grow rare palms and bromeliads, and am a good researcher.

Before I dive further though, do you think it’s possible to get what I’m dreaming of (i.e., oranges that taste similar to the ones sold in Riverside from by own backyard)? And if so, do you know where I could buy a tree like this?

* I live in Carlsbad (north San Diego) about 3-5 miles from the coast (no fog), and would put the tree in a sunny location at higher elevation. I’m willing to buy either a small or large tree, and can drive or pay to have it delivered. Thanks for any advice!

Hi Stacey,

I thoroughly understand your dream. I grew up in L.A. County where the climate was similar to Riverside (and maybe similar to where you grew up in Orange County), and where navel oranges reach peak flavor. That is my childhood memory too!

Then I moved to the beach and, ugh. I worked at UCSD for a while, and there’s a planting of navel oranges at the Salk Institute and I used to pick them but stopped bothering because those oranges never got beyond tasting watery and bland, just as you describe.

Now I’m twenty miles inland where it’s nearly as hot as Riverside and navel oranges taste as good as they get. The inland climate of more heat and chill is what seems to make the difference. Do you get enough heat in your location? I can’t imagine that you get enough to produce navels that taste as good as Riverside or the Orange County trees, but you could probably grow some that still taste very good. To increase the heat you could place the tree near a west-facing wall, if possible.

Washington navel is the specific type of orange that you want, I’m guessing. I have read that a seedling or sport of Washington navel called Trovita can get better flavor with less summer heat, but I don’t know this to be true firsthand. Trovita might also be worth trying.

Either way, I would buy a small tree rather than a large tree (small meaning five-gallon) as they are usually healthier. And small Washington navel orange trees are widely available at garden centers. You should have no problem locating one near you in Carlsbad. As for rootstock, don’t get too hung up on that. If you haven’t already, see my post: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/dwarf-semi-dwarf-and-standard-citrus-trees-what-are-they-really/

Thank you so much for the advice! I’ve read the blog posts you linked to, and it gave me lots of new ideas of areas I can research.

Most importantly, my husband and I finally did a “blind taste test” of several orange types (including store bought ones and oranges grown in a neighbor’s backyard). The clear winners in our testing were:

1) Sky Valley “heritage” oranges (supposedly done the “old” way on the same rootstock.

2) Cara Cara oranges (which I hadn’t tried before)

I wasn’t able to find a “Trovita” orange to try, but I do see a place in Vista where I can purchase a Trovita Tree. I’ll need to find one of these oranges to taste, as they do sound more tolerant of “less than full sun” growing conditions.

The Cara Cara result in our testing surprised me… it wasn’t *quite* as good as the Riverside ones, but pretty close! Do you think a cara cara tree might grow ok in my area (3-5 miles from the coast, with some sun but not ever getting super hot or cold)?

Last consideration (but an important one to me) is cosmetics. The orange tree is going to be a focal point of our yard, and I would really love to grow a beautiful mature tree in that spot (I never plan to move). Do you think either a “Trovita” or “Cara Cara” tree might look good… in addition to tasting great?

Here’s a Photoshop mockup of what I was originally picturing (though I can flexible on size or shape, as long as it’s sort of pretty) – http://staceywright.com/orange-tree.jpg

In other words, if you were in my position (3 miles from the coast, wanting a large beautiful, but also tasty orange tree)… which varieties would you be most likely to be looking at?

Thanks again for your help pointing us in the right direction!

Hi Stacey,

You can definitely grow an orange tree that looks like the Photoshop mockup. It will take many years, of course, but it’s certainly possible.

If I were doing it, I would try to grow a Cara Cara on a vigorous rootstock. Most oranges these days are grown on a roostock called C-35, which is a good rootstock but is a bit slower growing. (My own Cara Cara is on C-35.) Because you want a big tree, I would inquire at a local nursery about whether they might be able to get you a Cara Cara on C-32 or another faster growing rootstock. If not, no big deal; just more patience will be required on your part or you’ll have to pay more to buy a larger tree.

Great article. Thanks for posting. I am upstate in the lower Sacramento Valley region, northwest of Sacramento. Oranges taste great here as we get heat in the summer and fair chilling hours in the winter. Last winter we got a hard freeze that killed the scion of my four foot tall Meyer lemon and knocked back two small navels, a Washington and a Cara-Cara.

They are growing back but I just learned from you to look for the three leave clusters to make sure they are not rootstock.

I had the trees protected with the white frost cloth, but the freeze was too hard. I also had three newly planted avocados, a Mexicola, a Zutano, and a Stewart. Are avocados also usually on rootstock, as they are growing back?