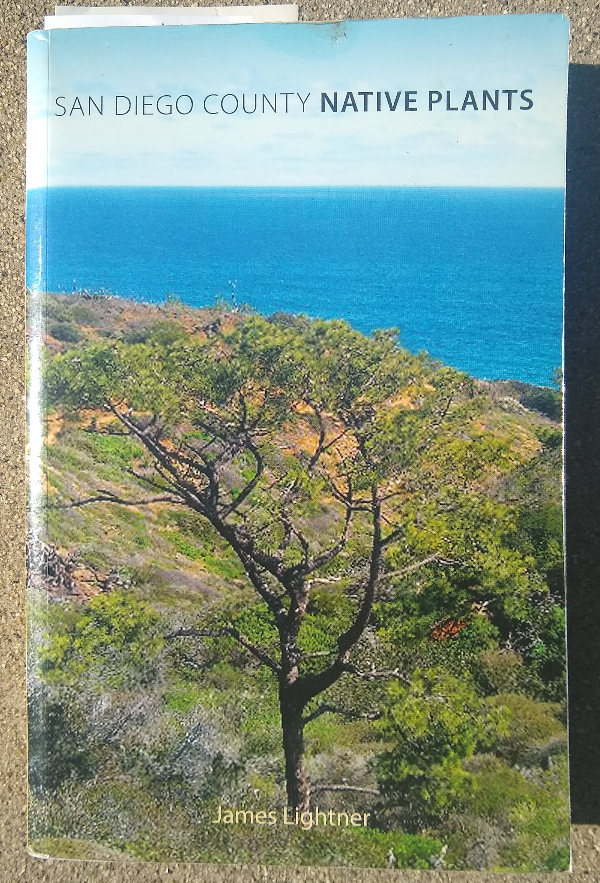

When I’m hiking and see a plant I don’t know, I consult my copy of James Lightner’s book. San Diego County Native Plants is my go-to resource for identifying and learning the basics about any wild plant seen anywhere in Southern California.

I’ve used this book for flora north of Los Angeles and out in the desert, and I’ve yet to see plants in the wild that aren’t in it. I’m sure some exist, but for me it’s been reliable anywhere in Southern California even though it technically only covers San Diego County.

The bulk of the book is a field guide, with abundant color photographs, most of which contain the flowers or fruit of a plant. This is helpful for identification. It’s often the flowers or fruit that cause me to notice a plant.

Well bound, I’ve owned my copy for about ten years and it has held up while being taken on travels and flipped through innumerable times.

The organization is in two main parts, with trees and shrubs in part one (think: big plants) and “herbaceous” plants in part two (think: small plants). Within these parts, the plants are grouped according to family. For example, the different oaks are together, and the plants in the pea family are together (lupines and lotus and vetch).

The book is user friendly, as it always places common names alongside scientific names; in fact, the common names are listed first. This is inviting. Most of us don’t go around calling a sage a “salvia.”

Scientific names have advantages, to be sure, but also drawbacks. One drawback is that taxonomists are always fiddling with them. One day monkeyflowers have the scientific name Mimulus aurantiacus and the next we’re supposed to call them Diplacus aurantiacus.

Just as helpful are the indexes in the back. One lists all plants by common name, and the other lists them by scientific name. So if you do hear someone mention Foeniculum vulgare, you can look it up and find that they’re talking pretentiously about fennel.

“Fennel? Fennel isn’t native.”

That’s another aspect I appreciate about this book: it not only includes native plants but also naturalized plants, plants that grow around here as if they were wild and native, without any help from us, but which were at some point introduced from other parts of the world.

When you’re out on a hike and see a plant that you don’t recognize, whether it’s native or not, you want to be able to find it in the book so you can learn what it is. And Lightner wisely made his book so that you can.

Preceding the main field guide parts of the book, San Diego County Native Plants opens with introductory sections on geology and soil chemisty, uses of native plants by wildlife, tips on when to see native plants in their glory, and more. Lightner is a clear and concise writer, and he packs a lot of interesting information into these sections. There is even a short section on landscaping with native plants; and I believe that a short section is all a gardener needs on this topic. As long as you plant the kinds of natives that are endemic to your location, then there isn’t much else you need to know.

Above is a Chaparral whitethorn (Ceanothus leucodermis) that I planted in my yard. It has grown happily because it belongs. I suspected it would because I’d seen these bushes growing wild nearby, and Lightner’s book helped me identify them.

However, for finding which plants would naturally grow on your property (before it was bulldozed and graded and built on or burned in a fire), San Diego County Native Plants is not your best resource. For that, consult the website Calscape. At Calscape, you can simply enter your address and up pops the native plants that are likely to have been there before you were.

The main feeling I come away with when I read San Diego County Native Plants is that the nature of Southern California is varied and wonderful. I do dream of having lived here a century ago when there was more of it, but even what we have left feels like a secret. We have bears and lions and eagles. We have sycamore trees and palm trees and pine trees. We have prickly pears and grapes and walnuts and blackberries. All native! All growing wild here!

Why is it that in school I was taught a lot about elephants and tropical rainforests and apples but less about our native flora and fauna?

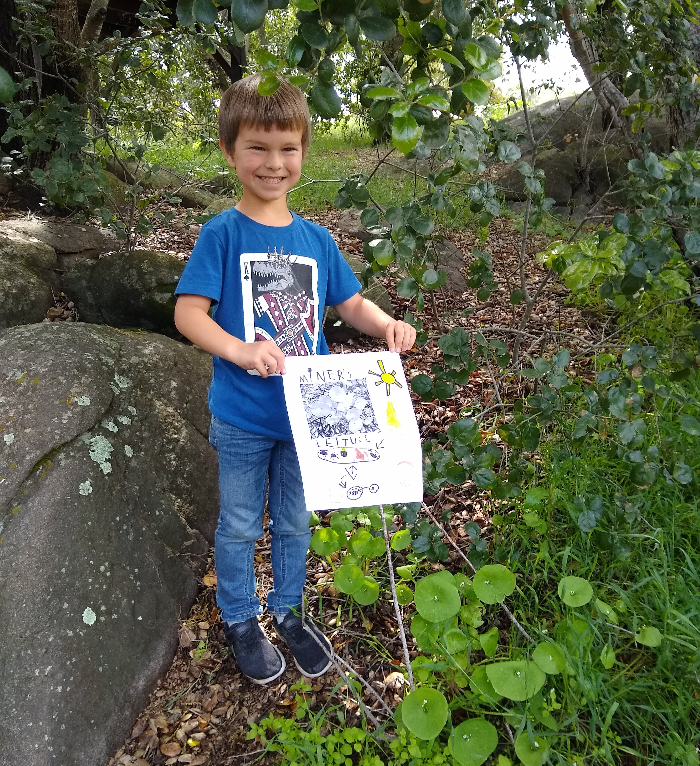

My kids love apples. That’s fine. My favorite fruit is avocados. But as I teach them a thing or two about avocados, I’m making sure that they are also getting to know what lives and grows wild all around them.

This is one of my sons displaying what he has learned about the miner’s lettuce found growing in our yard, with the help of Lightner’s book.

Where to buy San Diego County Native Plants

My other posts on Southern California native plants are here.

My other book reviews are here.

All of my Yard Posts are listed here.

Thank you for your support, which allows me to keep writing posts and keep them ad-free.

Third edition suggests it’s a good book! Great that the book includes common names for weeds, er, native plants. I sometimes let them grow because I’ve seen birds eating the seeds. I had a massive growth of wild tomatoes in my yard last year but they haven’t come back. I saved some seeds, though. Thanks for the tip about Calscape.

I live in the West L A area and have a fig tree (about 14 yrs old) which is secreting oil or resin of dark color that runs from its branches down to its trunk. How should I treat and cure it? The leaves are healthy and the tree produces lots of figs. Also, what is the best way to prune it? Thank you Greg, I’m new to Yard Posts, but like it a lot.

I use an app that’s free called picture this – it’s convenient and pretty accurate.

I take a picture with my apple phone and store it in my library. I always have my phone handy .

I’ll get that book tho – it looks great . Thanks for the info

Bob

Oh, I just cut down some tall weeds with fluffy fruits. Yeah, I let them get big. But a bonus. Those big weeds make a useful tomato stick. Snaps easily but bends pretty well. Birds picked off all the fluffy seeds. Could be a pea stick or a wife beating stick because it’s smaller than a thumb. Or a husband beating stick because it’s available. Sorry for so much joking around. Well, secretly, I can’t help it.