Over the past few summers, some of my vegetables have performed worse and worse because of damage from root knot nematodes. What are root knot nematodes? They’re microscopic worm-like creatures that live in the dirt and bore into the roots of plants and interfere with the ability of those roots to feed the plants. Read more about them in my post from last summer, “What are root knot nematodes?”

It was last summer that I began taking root knot nematodes (RKN) seriously. In this post I’ll go over the strategies I’ve been using for dealing with them, along with the results thus far.

Remove roots with knots

My gardening habit had been to cut off old plants at soil level and leave their roots in the dirt to decompose, but lately I’ve changed to ripping roots out to check for RKN galls — and if I see any, then I try to rip all of the roots of that plant out and take them to the trash, never adding them to my compost.

Inside the galls is where the nematodes and their eggs live, in addition to being in the surrounding soil. So removing those galls reduces the numbers of RKN.

Extra compost

Another of my gardening habits is to add compost to my vegetable beds for fertility and enhanced soil structure. I now do this times two or three.

We’re told that soil of the highest fertility helps grow plants that are stronger to fight the effects of RKN better. (See nematode management advice from the University of California.) I’m afraid I had been only giving my vegetable beds enough compost, not as much as might be optimal. I had been adding about two inches worth per year; now I’m adding more like two inches worth at every planting, and I plant each bed two or three times per year.

Plant early

Root knot nematodes are said to be most active in warm soil. I’ve certainly seen my plants suffer most from June through summer into fall, and that’s when soil is warmest. So one way to avoid the damage from RKN when they’re most active is to not put in new plants from June through summer into fall. Put in new plants well before this time or after.

I therefore committed to getting an early start — as early as wise in other respects, such as climate and pest pressures — to vulnerable plants like tomatoes, cucumbers, zuchinni, and peppers this year. I got my tomatoes, cukes, and zukes sown in January, and I put the plants in the ground on April 9. My peppers came as seedlings from Territorial, and they also got in the ground on April 9.

Plant elsewhere

But I cheated with my peppers. Rather than planting them in my established vegetable beds, where I know the RKN population is high, I planted them in another part of my yard. There I don’t think there are many, if any, RKN in the dirt.

Here are last year’s peppers:

Here are this year’s peppers:

Planting elsewhere is a viable strategy if you have the yard space for it. In addition to peppers, I planted my cucumbers and zuchinni and tomato varieties that aren’t resistant to RKN in other parts of my yard. They’re all growing and producing fine as of here in mid June, which says that RKN was probably a problem for them at this time last year — those that were in the garden beds, anyway.

Last summer I also planted some cucumbers in my vegetable beds but others elsewhere, and the difference in plant performance was clear. I planted the cucumbers pictured below in a vegetable bed last year on April 30, and by mid-June they were stunted, yellow, and I removed them.

On the other hand, I planted this cucumber under a pear tree on the same day last year and took this photo in mid-July:

Plant in pots

Also an option is planting in pots. Some vegetable plants do very well in pots.

For example, I had good results growing lettuce in one-gallon pots last summer so I’ll be doing that again this summer. In the pots I used my own compost, but I would recommend using Recipe 420 if you don’t have your own compost. (See my post, “Comparing four mixes for starting vegetable seeds.”) (Also see my post, “Growing lettuce in summer in Southern California.”)

Grow resistant varieties

For some crops, there are varieties that have shown resistance to RKN. Tomatoes are the most common. So while I’ve planted some tomatoes in other parts of my yard, I’ve also planted tomato varieties that claim RKN resistance in my vegetable beds. At this time I have growing Damsel, Big Beef, BHN-1021, Lemon Boy, and Mountain Fresh Plus. All are looking good and producing acceptably so far, and they’re producing slightly better than the tomato varieties planted in the vegetable garden last year which did not claim resistance to RKN.

Here are some of last year’s tomatoes:

Here are some of this year’s tomatoes:

Grow non hosts

Root knot nematodes don’t attack every vegetable we grow. Because of this, I’ve been able to continue to grow non-host plants in my vegetable beds this summer, such as corn. In fact, I’ll be growing a lot more corn this summer than in the past few summers, just because I can!

See a list from the University of California of plants that are hosts or non hosts for RKN here. (Note that “cole crops” is listed as a host or suspected host of RKN; however, I’ve never seen RKN galls on cole crops nor have I seen poor growth from them in my garden, even on those I’ve grown into the summer.)

A further benefit of planting vegetables that don’t host RKN is that these plants reduce the RKN population in the dirt since RKN do not have roots to feed on.

Summer fallow

With a similar aim of reducing the RKN population, I’ve just left many of my vegetable beds empty for the summer. It’s not a pretty look, sadly. The garden looks spotty, hot, and neglected, but it is for a good cause (assuming it works!).

From the UC nematode managment guidelines: “Fallowing for 1 year will lower root knot nematode populations enough to successfully grow a susceptible annual crop. Two fallow years will lower nematode numbers even further.” They estimate “an 80 to 90% per year reduction in root-knot nematode populations.”

Beneficial nematodes

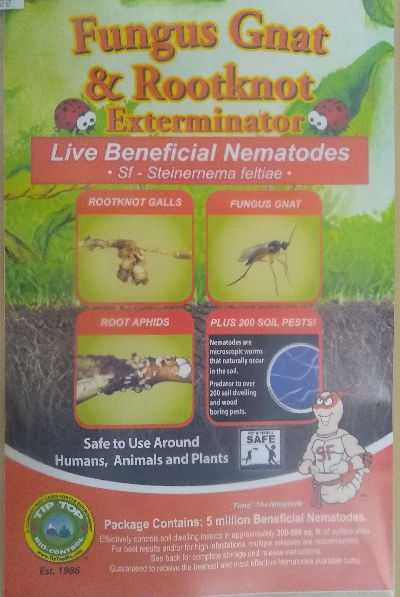

When I asked a farmer friend for advice on dealing with RKN, he told me that in addition to growing resistant varieties, he also applies beneficial nematodes. Specifically, he applies “Fungus Gnat and Root Knot Exterminator,” which is a batch of millions of Steinernema feltiae, a species of nematode that kills root knot nematodes through infecting it with a bacterium that it carries called Xenorhabdus bovienii. (This particular product can be purchased at a good nursery or online here, but others sell this species of beneficial nematode online too.)

So for the past year I’ve been buying these beneficial nematodes and applying them to all of my new plantings. At $20 per bag of five million, they’re not cheap but worth it if effective. I’ve applied three bags to my twelve vegetable beds over the past year.

It’s possible that they’ve been helping since my recent (late spring) harvests of carrots, beets, and lettuce, which have had RKN galls on their roots in the last few springs, have had few to no galls this spring.

Conclusions

I only say it’s possible that the beneficial nematodes have been helping because I don’t have a second garden or second set of beds that haven’t received the beneficial nematodes (a “control”) for proper comparison. (In this study done on tomatoes in Turkey, the application of this species of beneficial nematode did achieve good results compared to a control.)

Moreover, I’ve been implementing many other strategies simultaneously (extra compost, removing roots with galls, using resistant varieties, etc.) in all of my beds so I really have only a hunch as to what is helping and what is not. I’ve even been watering a little more compared to last year. Plus, the RKN do more damage as the summer wears on (they thrive in warm soil). I’ll update this post in the fall.

What I can say is that it doesn’t seem like anything I’ve been doing has been hurting. So I would suggest that all of these strategies are worth exploration if you’re dealing with root knot nematodes in your vegetable garden.

Untried or unappealing strategies

A few methods of dealing with RKN that I have not tried include soil solarization and nematicides (poisons that kill nematodes).

Also, I have not found growing French marigolds or other RKN-suppressive crops appealing. Last summer, I grew Queen Sophia marigolds in one bed, but I felt like I was wasting water and effort, wondering if I could be getting a similar effect by fallowing — in other words, by doing nothing.

I have the same thoughts about growing arugula or mustards that are said to be harmful to root knot nematodes. I’ve decided that I’ll only try those once easier and cheaper options fail.

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

Supporters donate to allow me to continue writing Yard Posts and keep the website ad free. To them I say, Thank you. Learn how you can support HERE

I’m dealing with RKN in northern Florida. Do you have any update on which time-tested methods have proven to help?

I read somewhere that marigolds might ward off nematodes. Ever heard of this?

I see you covered that already. Whoops!

(knock on wood – raised beds) I don’t think I have RKN? How would I really know? I grow mostly in raised beds but this year I hoarded so many of my own tomato starts I’m planting the overflow in the ground where I previously had sunflowers last year, then cover crop, then added tons of new soil. So I’d need to pull up anything at the end of the season and check? Thanks!

Have you tried solarizing the soil before spring planting?

Hi Kimberly,

I have not, but I think you need the intensity of the summer sun to do a good job of solarization. (You need to heat the soil to a sufficiently high temperature and depth.) But I’d like to try a late-summer solarization sometime, maybe this summer.

Hi Greg,

Yup. RKN infestation in at least 4 of 11 raised beds. I knew I should be rotating crops, but I just couldn’t help planting…. Thank you for your research. I found the same articles, but the Fungus Gnat and Rootknot Exterminator Beneficial Nematodes info is new. The real bummer of fallowing (which I will do as well) is that one still has to keep the beds moist! So now one has the major cost of summer water, with no end products. Ack. This is one costly obsession! Best of luck and please keep us updated.

Hi Cara,

It really is no fun dealing with RKN. But so far I’ve noticed clear improvement where I’ve not planted susceptible varieties or crops for even one summer. The rotating/fallowing seems to reduce the RKN population significantly. This summer will be second or third summer rotating/fallowing a few different veg beds, and my plan is to try susceptible varieties and crops next summer to test.

Remember that you don’t need to keep the area empty in order to reduce the RKN. You just need to plant varieties or crops that the RKN don’t use. For this, I go for corn, brassicas, and various flowers including sunflowers. I also continue to plant RKN-resistant tomatoes (mostly Mountain Fresh, BHN-1021, and Galahad).

I have found that a lot of perennial edible crops are not very prone to RKN – we grow asparagus, rhubarb, Jerusalem artichoke, globe artichoke, ginger, turmeric, and pepinos with little if any RKN problem in a full sun, frost-free sandy garden in Sydney.

(Our summer pumpkins, tomatoes, eggplants etc have lots of RKN).

However I have read that different regions of the world have different RKN – Australia having slightly less varieties because of its isolation. ie ymmv

Not all perennials are immune – eg I have had passionfruit badly affected.

Hello nematode foes, I am also in San Diego county (Vista) and just had to pull all my tomatoes and peppers from 3 raised beds because of moderate to severe RKN infestation. The tomatoes were a total loss this season, while some of the peppers failed and some produced moderately well. The interplanted onions did fine (non-hosts).

I am going to try the marigold/mustard treatment, along with shrimp meal which is supposed to add something (chitinase?) which I understand helps control nematodes. The marigold seeds are planted and mulched now, waiting for them to germinate.

I will probably add the beneficial nematode product you mention above Greg. If it’s of interest, I can post updates here as the process goes on.