I’ve got a cart of vegetable seedlings ready to be planted. Where will they go?

My general rule has been to avoid planting the same crop in the same spot two years in a row. So, for example, since I planted tomatoes in Bed 2 last summer, I won’t plant tomatoes in Bed 2 this summer.

Waiting longer before planting tomatoes in Bed 2 is even better. Why?

In this post I’m going to take a trip down history lane to answer the “why” of crop rotation and then share some ideas for how to rotate certain vegetables and how to rotate within limited garden space.

What happened to crop rotation?

Crop rotation is not practiced on U.S. farms as much as it once was. Since about the 1950’s, when chemical fertilizers and pesticides came into wide availability and use, farmers turned to planting a single crop in a field over and over, year after year.

In agriculture texts of old, however, you find crop rotation being referred to as a practice that almost all farmers did. And detailed schedules for rotations were advised.

The 1938 Yearbook of the USDA gives the main reasons that crop rotation was commonly practiced:

“Crop rotation not only tends to favor higher crop production, but as a rule insures better crop quality than continuous cropping. There are numerous cases on record to show the advantageous effects of rotating crops on yield and quality. The fact that the ravages of insect pests and of plant diseases are reduced to a minimum in a crop-rotation system as compared with continuous cropping is an insurance for better crop quality.”

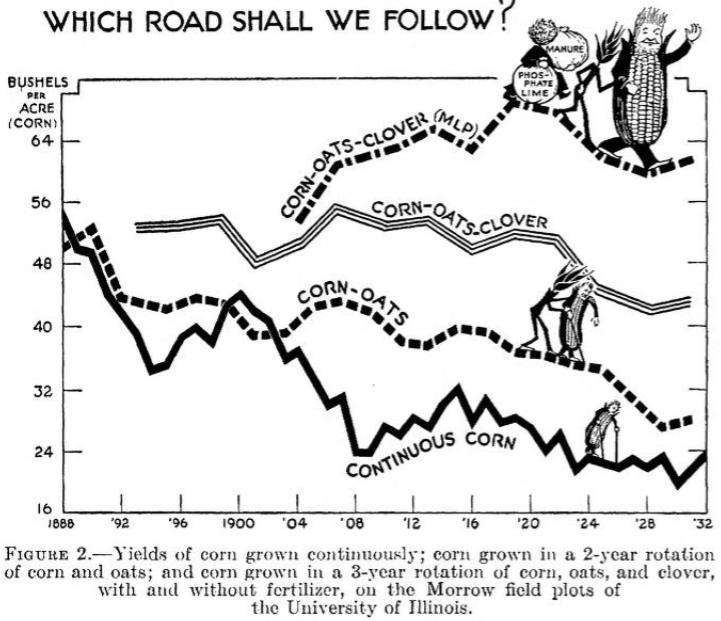

Here is a graph from the 1938 Yearbook showing the higher yields in a crop-rotation system in Illinois over the years 1888 to 1932:

If crop rotation was clearly advantageous, then why did farmers change? Again from the 1938 Yearbook:

“When the [first] World War terminated, the huge chemical plants, geared to capacity production of wartime necessities, faced a difficult situation. In order to avoid ruin, these plants turned to the manufacture of nitrogen and other compounds for fertilizer use.” (page 489)

In essence, the belligerents developed explosives and poisons for the wars and then transformed those factories into producers of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. And farmers gradually switched from using the tools of crop rotation and manures to growing single crops and using new chemicals to achieve and maintain high yields and control of pests and diseases.

There is more to the story, of course. And the switch wasn’t a complete switch. But suffice to say, there is far less rotation and manure use on farms today, and there is far more monoculture and chemical use.

How is this relevant to me and you, the home vegetable gardener? Our home gardens are more like the farms of old (pre-1950) and less like most of the farms of today. We grow many different crops, and most of us prefer to use little or no chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Therefore, we’re likely to benefit from emulating some of the traditional rotation practices in our little plots.

Rotation times

Before getting distracted by the details, I want to say that I think the most important thing is to simply avoid planting the same crop in the same spot year after year, to do some rotation. Skip at least a year. That’s easy to remember and it does help.

Now also notice that the best results come from rotations longer than just two years. In other words, the highest yields and quality come from planting a crop in a given spot only every three or four (or more) years. For example, in the 1938 USDA Yearbook graph above, the higher yields of corn were from the three-year rotation as compared to the two-year rotation.

And look at the rotations practiced by some vegetable farmers today in “Crop Rotation on Organic Farms: A Planning Manual.” See page 49 of the manual (page 57 of the PDF file). They are all four- or five-year rotations. For example, Anne and Eric Nordell only plant onions in a given spot on their farm every four years.

Looking at my own records, I notice that I usually get my best results from rotations longer than just two or three years. I am going to try to implement longer rotations from now on in my vegetable garden.

Rotation sequences

Which crops should follow others? In other words, if I don’t plant tomatoes in a spot for four years, then what should I plant there? There is disparity among farmers and researchers on this.

I have not kept track of crop sequences longer than three in my own gardens. Mostly, I’ve only kept records of sequences of two. So really, I have no research to contribute. But here are a few pairs that I’ve seen like to follow each other, in that they’ve given good results in multiple years.

1. Corn-potatoes, or potatoes-corn. Corn sown about March and harvested about August, then potatoes sown between corn stalks in August. (Stalks shade the soil for a bit until potato plants are up in growing, and then I cut the stalks to the ground.) And potatoes sown about February and harvested about May, then corn sown.

2. Broccoli-tomatoes, or tomatoes-broccoli. Roy Wilburn clued me into this rotation, which he uses on his small farm, and it works for me in my small garden too. The latest cauliflower or broccoli will be harvested in May or June, and then tomatoes follow. Or the earliest tomatoes planted in February or March that then burn out in the middle of summer can be followed by a planting of broccoli or cauliflower (seedlings) in about August.

I have been incorporating more grains (wheat, oats, barley) and sunflowers and fava beans into my rotations too, and I like the results. Some of the produce we eat, and some we give to the chickens. I want to expand the use of these types of crops in my rotations.

Overall, I want to experiment with longer rotations and a broader range of crops. I will draw inspiration from the sequences in “Crop Rotation on Organic Farms: A Planning Manual” and adjust the planting dates to be appropriate for Southern California.

How to rotate in a home garden

It’s one thing to move crops around in space and time across 100 acres, but a more challenging task to rotate within one or two vegetable boxes. Here are some strategies that I’ve used that might work for you too.

Different side of bed or box

You can move to a new side of a bed or box, or a new end of a row. I do this with crops like Brussels sprouts and green beans, which I don’t grow much of.

Move into a container

A container can be filled with “new” soil so it is growing that crop for the first time, in a sense. For summer carrots, I rotate “out of the ground” and grow in containers. I do the same with summer lettuce. In cooler seasons, I grow most carrots and lettuce in the ground.

(My posts, “Growing carrots in containers” and “Growing summer lettuce.”)

Change the bed or box

If you grow a lot of one crop and have the space, the most obvious rotation is from one whole area to another, whether it’s a bed, a row, or a raised box.

Move the dripline

I grow the majority of my vegetables in the ground, and I irrigate them with driplines. The paths between the beds are covered in wood chips. Occasionally, I rake the wood chips off a path and turn it into a planting bed. The wood chips have been decomposing and forming a nice layer of compost underneath. I bend the dripline and stake it to irrigate that former path area, or I punch in a new dripline there. It’s like an entirely new bed.

Move to a fruit tree

I grow some summer crops at the canopy edge of a fruit tree. This opens up a lot more space for rotation. The crops I often grow under fruit trees are melons, pumpkins, and cucumbers.

(See my post, “Growing vegetables under fruit trees”)

Fallow

Finally, although not exactly a form of rotation, leaving a spot or bed empty for a season or a few years accomplishes the same goals. The downside is that nothing is reaped from a fallowed bed. If I fallow a vegetable bed, then I also apply compost or another mulch so that the time is used to break them down further and be primed for the future planting. Once I do plant, it is as if a multi-year rotation has occurred.

A related post:

My Yard Posts have no ads because of your support. Thanks!

My Yard Posts are categorized and listed here.

Hi Greg, I realized it was Saturday afternoon and wondered if you were OK, Friday’s yard post not having arrived. Glad to hear the delay was research related and nothing serious! I really enjoyed the rotation article; worth the delay.

Thank you, Peggy. I unexpectedly opened up a can of worms with this one, and I’m still reading deeper today. My vegetable garden is likely to look very different in the next couple years, and hopefully better!

I’m sure most gardeners know this, but legumes like clover and beans have nitrogen “fixing” bacteria in nodules on their roots. Including legumes in a rotation puts nitrogen back into the soil following a nitrogen hog like sweet corn. In my experience in Irvine California, the soil doesn’t need much phosphorus or potassium. I cheat and use pure urea (46% nitrogen) or ammonium sulfate (21% nitrogen) dissolved in water.