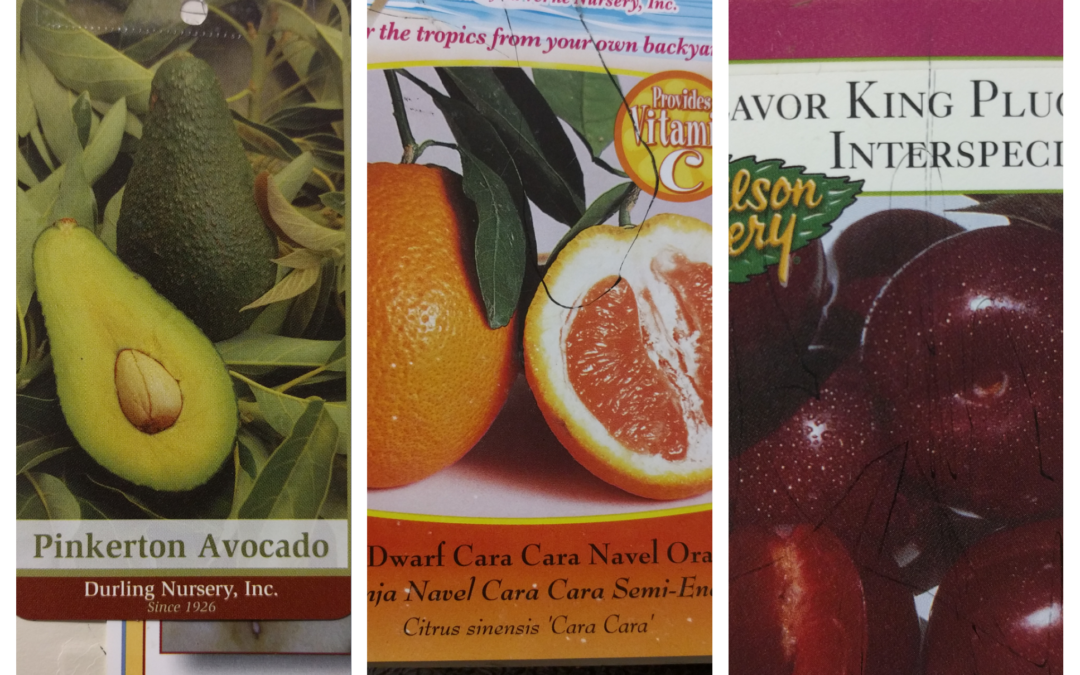

We buy a fruit tree — a Pinkerton avocado, a Cara Cara navel orange, a Flavor King pluot — and we think the tag tells us what we’re getting, but it tells only half the story. Almost every fruit tree you buy has been grafted. In other words, almost every fruit tree is two trees in one. Why are they doubled up like this? And what difference does it make to us, as we care for it in our yard?

Why fruit trees are grafted

If you taste a Flavor King pluot from the tree in my yard and like it (and I think you will), and you decide that you’d like a Flavor King pluot tree of your own, you can’t plant the seed from that fruit and get a Flavor King pluot tree. You’d get a tree whose fruit was different, just like you’re different from your parents. Might be better, might be worse, but different for sure.

See pictures of how variable the fruit is from trees that all grew from Hass avocado seeds in this article.

That’s why fruit trees are grafted. Because it’s the only way to replicate them. (There are a few exceptions, like figs and pomegranates.)

What is grafting? In the simplest terms, it is connecting one tree to another, such that they fuse and grow together.

What happens is one tree is grown — usually from a seed — and it serves as the bottom half of the grafted tree, called the rootstock. If it’s a Flavor King pluot we want, then we take a piece of a branch from a Flavor King pluot tree and connect it to the rootstock tree. In the end, we’ll have two trees in one, where the roots and part way up the trunk are the rootstock tree, then there’s a graft union, and above that is the Flavor King pluot part that has branches and leaves and the Flavor King pluot fruit. The tree will make exactly the same fruit as the original Flavor King pluot. It is, in this sense, a clone.

So what?

It’s unfortunate that the labels that come on the fruit trees we buy do not tell us that the trees are grafted. They would also do well to warn us about rootstock suckers.

Have you identified the graft unions on your fruit trees? If not, I’d recommend doing so today. It could save the lives of your trees. Here are examples of graft unions on some of my trees.

You’re looking for a change in shape or color in the trunk, usually around six inches above the ground. That’s where the rootstock connects to the scion (the top part of the tree that gives the fruit you want). Sometimes the graft union is obvious, but particularly on old trees it can be hard to make out.

And here is the reason you want to locate this union: Any branch growing from below it must be removed, and hastily. A branch growing from below the graft union is called a rootstock sucker. If left to grow, it will probably eventually produce fruit, but its fruit will not be the Flavor King pluots or whatever kind of tree you bought. It’s fruit will be nasty, or at least strange.

Have you ever heard anyone say that their orange tree is producing some sour fruit? One of my neighbors said so, and she proffered that the orange tree might have cross pollinated with a nearby lemon. Nope. Doesn’t work that way. Rootstock suckers.

This brings us to the more urgent reason to remove rootstock suckers immediately. If left to grow, they often overtake the scion (e.g. Flavor King pluot). They shoot up very fast, grow taller than the top (scion) branches, shade them out and kill them. In time, your tree morphs from the tree you bought to a tree whose fruit is all mysterious.

When we moved into our house four years ago, there were many neglected fruit trees in the yard. The previous owners had been elderly and lost the interest or ability to care for them. One of the trees looked like a huge peach bush. That summer, it bore many small, bland peaches. Eventually, I climbed in and found that inside there was a thick trunk of an old peach tree that was now engulfed by numerous, more vigorous rootstock suckers. The old peach branches in the middle were barely still alive. I saved that old peach.

Grafting videos

Watch a video of a how deciduous fruit trees are grown at Dave Wilson Nursery. At about 3:30 you’ll be astonished by the speed at which the professional grafter does his budding work. Dave Wilson supplies many deciduous fruit trees to retail nurseries throughout Southern California. It’s where my Flavor King pluot came from.

And notice how avocados are grafted using a different method in this video from an avocado nursery located in New Zealand. The same method (usually called “tip grafting”) is used in nurseries here in Southern California. The actual grafting can be seen starting at 1:45.

You might also like to read:

Well written, entertaining, informative, with meaningful links to suit the fancy. Thanks much, Greg!

Thanks, Jeff!

I was so happy when I read that you saved the old peach tree!

Now I need a Flavor King Pluot!

Such and interesting article!

Thanks, Renee! I have to say that pluots in general have won me over. Dapple Dandy might be my favorite pluot, but they’re all a little different, they all taste great, they have a long harvest window, and at least in my yard, they grow so reliably every year.

Thank you for the most interesting and needed information.

Greg, can you tell us about how to treat an older tangerine tree that has so much fruit that it seems too heavy for the branches? Unfortunately, I do not know the type of tangerine but they usually are “ready” late December/early January.

Thank you so much!

Hi Beverly,

An overperforming tangerine tree, eh? You’re probably safe doing nothing at all at this point. Since they’ll be ready to eat soon, it’s unlikely that they’ll get any bigger and heavier.

Citrus wood is amazingly flexible. I’ve personally never seen a citrus branch break under the weight of a heavy fruit load, even large oranges or grapefruit. My Valencia orange tree had an extremely heavy fruit load two years ago but nothing broke. My Gold Nugget mandarin had a very heavy load last year and nothing broke.

It certainly won’t hurt the tree if you thin the fruit from some laden branches, but it’s probably not necessary to prevent limb breakage. I say probably because I can’t see your tree, and it’s possible that something exceptional is going on with it.

I have a tangerine seedling in my yard and it now has a green leaf with stickers as a branch coming out the side of it underground and growing along the trunk? Is that a rootstock if I have described it properly

Hi Brian,

Did you buy this tree? And did it have a label on it with the name of the kind of tangerine it is supposed to be?

What you describe does sound like a rootstock sucker but only if you have a grafted tree. If it is a “seedling” then it has not been grafted. A seedling tree is a tree that has been grown from a seed, and calling it a seedling implies that it has not been grafted. Sorry if this sounds pedantic, but I’m just trying to figure out exactly what kind of tree you have so we can deal with it properly.

Hi,

We have a Eureka Lemon tree.

We pruned it heavily last year. We have discovered numerous branches that are very thorny. I cant identify the graft line but it is a tree with two trunks. The thorny branches eminate not only from lower down but higher up the tree also.

One side is going crazy with thorny branches and the other seems thorn free.

Do we chop the effected side down? The whole tree is about three meters high

Hi Kathryn,

Are the thorny branches only emanating from one of the two trunks?

Is there fruit on the thorny branches as well as the branches that don’t have thorns? And does the fruit on both look the same?

Hi Greg,

Thanks for your response.

Yes the thorny branches only emanate from one side. It isn’t fruiting at the moment but I’m very interested to see what happens when it does.

After doing more research I think I have the answer.

The thorny side is more than likely a Lisbon lemon. The nature of its branch growth is typical to what is described, i.e more vertical. This would’ve been the original graft.

The other side has a spreading branch growth more typical of the Eureka and no thorns. The tree (we thought) we originally purchased.

If this is the case, do we just accept that and nurture them both? Two for the price of one? 🙂

Thank you and I look forward to your response.

ps “Original graft” should read “root stock”.

Hi Kathryn,

That’s certainly a reasonable approach. Wait to see what kind of fruit you get from each, and then decide whether to keep both or remove one.

Thank you for this article! Now it makes sense why my Yosemite Gold Mandarin has three different branches, one bearing fruit, one plain and a third very thorny lemony branch! I have gone ahead and trimmed the thorny lemony branch ( rootstock) as close to the ground as it seems to be growing from the ground. Not sure what I need to do with the second, non producing branch! Wish I could attach pics for reference…

Can you graft scion wood from say Haas or Fuerte cuttings onto a vigorous avocado rootstock sucker “tree” to get those varieties to fruit?

Hi Spencer,

Yes, you can. I have done exactly what you describe.

Great! I have been planning to do that and have located a grower in Fall Brook who may be able to supply me with scion wood this fall.

I live in Clairmont, San Diego but have had trouble establishing a grafted tree in the heavy soil there. With my last attempt the grafted scion withered away within 6 months of planting but then two strong root stock stems emerged and shot up over the last two years to about ten feet with luxurious growth. Cross fingers I can master stem grafting.

Hi Greg

Whilst googling why my lemon tree has fruit only on the grafted side I came across your post. Really interesting by the way. I hope I’m not too late for your advice.

I purchased a grafted eureka a few years ago and it is now bearing fruit (quite a lot actually) but only on the grafted site. The original rootstock has no fruit and has grown abnormally tall, way past the grafted side of the tree. My question is do I cut the rootstook back down to match the grafted side and is it ever likely to produce edible fruit at some stage.

There are no rootstock suckers.

Thanks

Hi Greg,

Thanks for your wonderful posts and information in your site. I learn something new in each article.

I took 2 small branches from Meyer lemon tree and one small branch from a lemon tree from a near by Citrus Park and planted them in containers 2 1/2 years ago. I now have 3 small trees (2 1/2 feet high) that are bearing fruit; however, they don’t have a rootstock as the base. Is it ok to grow these trees? They look healthy and are growing. Right now at the end of Feb 2023, they all have flowers. They produced a handful of fruits each last year which I harvested last month. Should I worry about not having a rootstock? Thanks.

Hello, Mr. G…

I just spent some time yesterday digging up and potting 9 peach tree saplings, was giddy thinking I was going to create a free peach orchard. Then my friend told me they might be sterile if my original tree was grafted.

The tag has long blown away, but if memory serves, it is a Contender. Are they always grafted?

What should I do with 9 peach trees? What would you do?

Middle Tennessee

Thank you and God bless!

Hi Priscilla,

If your original tree had a tag with a variety name (such as Contender), then it was likely grafted. If the saplings you dug up grew from seeds from the fruit that fell from that tree, then they will become trees that make peaches somewhat similar to the fruit from the original tree.

I would grow them out as you intended. They’ll probably all make decent fruit, some better than others. I’ve grown peaches from seedlings and had such results. In fact, a seedling peach tree from a friend’s yard makes some of my favorite peaches, better than many varieties available from nurseries.

This is informative but understandable, thank you! Would you say sprouts from the spot of the root graft count as rootstock too, or just below?

Hi Lindsay,

Sometimes it’s hard to tell so you can just prune those out to be safe or let them grow but keep an eye on them to see if their leaves look different or if they’re extremely thorny, etc.

Hi Greg, I have kumquat, lime, lemon, and kaffir lime trees in pots, I bought them last year. Previous owner had them for 10 years and were healthy and bearing fruit. I don’t know what happened to those trees. They started losing the leaves at the end of last summer. Could have been too long under the sun (all day) or shock when I moved them from one place to another when I moved to a new place. They lost all the leaves when I put them inside during winter. This summer, I thought they were dead because it took them a long time to bounce back. So, I trimmed those branches (a lot) because they were all over the place and to see if they were still alive. I noticed they were still green inside the branches. Now, I see leaves coming out from under the graft union on the lemon, lime and kaffir lime trees. The kumquat also started to grow new leaves, but above the graft union. I was told that my trees are dead, it’s just the rootstock still alive. What can I do to revive those scions? Can I do air layer on those branches after I remove the rootstock suckers?

Hi Natalie,

I think the only way you can hope for the scions to revive is to care for the trees well and wait for them to show growth. If they do, great. If they don’t, then you’re out of luck and can use the rootstock growth for grafting if you want.