Nothing about the story of Shiranui is straightforward. There is mystery and there is hype. Even my own Shiranui tree (above) is complicated. But let’s start with the name.

In stores, Shiranui mandarins are sold under the trademarked brand name “Sumo.” You may have seen them lately.

Shiranui is a variety of mandarin that was developed by researchers working for the Japanese government back in the 1970s, according to Citrograph Magazine. It was officially named Shiranui but also later gathered other names, such as Dekopon and Hallabong (in Korea).

Shiranui budwood was eventually imported into California, legally and illegally, by numerous people. According to David Karp, writing in the Los Angeles Times in 2011, the most important importation was done by Brad Stark in 1998, as it was his budwood that led to Sumo. A company in California’s Central Valley called Suntreat bought the rights to Stark’s legal Shiranui budwood and assembled a club of citrus farmers to grow the trees and sell the fruit under an exclusive and confidential agreement. If anyone asked about their trees, they were to call them “XP1.” But once they started selling the fruit in 2011, they would call them “Sumo.”

(The Sumo brand is still owned by Suntreat today, but Suntreat is now owned by Agriculture Capital, an investment fund based in Portland, Oregon.)

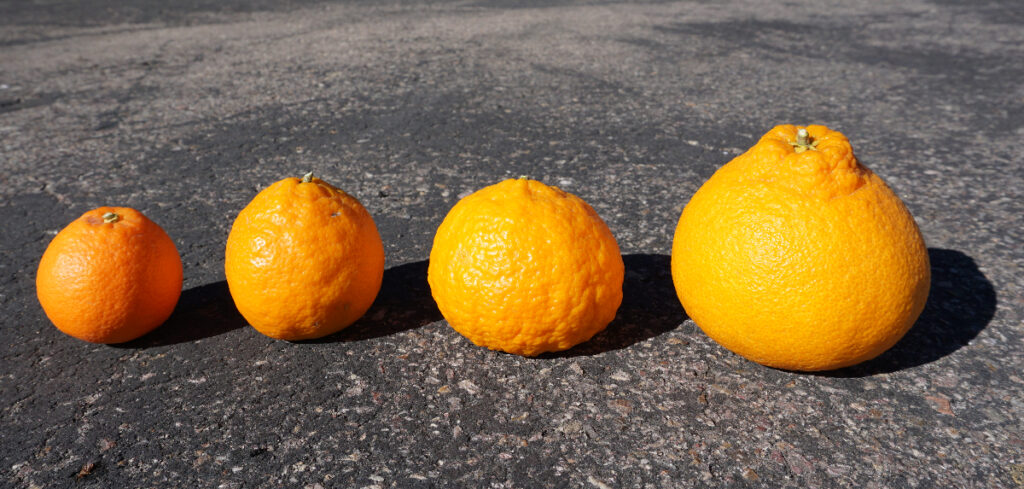

Shiranui mandarin fruit

Shiranui fruit are big for mandarins, but they’re not true mandarins. They are said to come from a cross between a Ponkan mandarin (specifically, Nakano number 3) and Kiyomi tangor; a tangor is a “tang-or”, a tangerine (mandarin) crossed with an orange. In size, Shiranuis are between a typical mandarin and a typical orange.

But the most remarkable characteristic of a Shiranui fruit is its neck. Most (not all) Shiranuis have a protrusion at the top, which comes in handy at eating time because it can be popped off to start the peeling.

Shiranuis peel easily. Inside, the segments are seedless, the juice vesicles are large and crisp, and the flavor is rich. Early in the season, I taste a hint of grapefruit in my Shiranuis whereas later in the season they become intensely sweet.

I find eating Shiranuis very enjoyable. Others feel even more strongly. In this mandarin, some have found the promised land.

David Karp: “I still remember the first time I tasted the legendary fruit the Dekopon [Shiranui]. Think of a huge mandarin, easy to peel and seedless, with firm flesh that melts in the mouth, an intense sweetness balanced by refreshing acidity, and a complex, lingering mandarin orange aroma. I’ve tasted more than 1,000 varieties of citrus, and to me the Dekopon is the most delicious.”

From my tree in San Diego County, Shiranui fruit begin tasting good in late January and they become too sweet sometime in April. I prefer to eat them around late February into March.

To put the Shiranui harvest season in context, in my yard the Shiranuis taste good after the Satsuma and Kishu mandarins but slightly before Gold Nugget and Pixie mandarins.

Homegrown Shiranui fruit compared to store-bought Sumos

The first Shiranui I ate some years back was from a grocery store and branded Sumo. It was good, good enough to encourage me to grow the variety myself. I hadn’t eaten another store-bought Shiranui until last week, when I decided to give one a try in order to compare it to my homegrown fruit.

The Sumos in the store were not attractive on the outside. They looked beat up, with browning here and there on the peels, and the creasing in the peels suggested they had been off the tree for a long time. Inside was worse though. The flavor was sweet but insipid, and the texture was flimsy.

By comparison, my Shiranui had more complexity of flavor and the flesh burst as I chewed it.

I didn’t even finish the store-bought Sumo. It saddened me to think that someone would buy this fruit and then think he had experienced the variety’s potential.

I have read that some people let Shiranui fruit “cure” for a while after harvesting. In other words, they let the fruit sit around for a few weeks, as this reduces the acidity. If this is what is done to the commercial Sumos, I think they’re making a mistake.

Shiranui mandarin tree

I like the way Shiranui grows. It is fast, with stout branches, and it also fruits prolifically. I have had to remove a lot of fruit each year from my tree in order to prevent branches from breaking under the vast amount it sets.

My Shiranui tree is young, but it has a story. It began as a Pixie mandarin tree. In June of 2020, I budded Shiranui onto the Pixie tree, having gotten budwood from the Citrus Clonal Protection Program. (This was lucky, as competition for the limited supply of Shiranui budwood from the CCPP was fierce.)

In the spring of 2021, the newly grown Shiranui branches bloomed and set more fruit than the entire remaining Pixie portions of the tree. Last spring, the Shiranui branches again set a ton of fruit, more than the Pixie.

I have observed a few Shiranui trees elsewhere, and those trees also make a lot of fruit.

Shiranui always seedless?

Even though the Shiranui mandarins from my tree have always been seedless, as have those from the store and those I’ve eaten from a friend’s tree, I have read reports of some Shiranui trees making fruit with seeds.

For example, within the Citrus Variety Collection of the University of California, Riverside they have found seeds in their Shiranui mandarins. This was at two locations: Riverside and Exeter. Importantly, their trees are said to be made from the same budwood used to make mine (VI 860 from the Citrus Clonal Protection Program).

It seems that Shiranui fruit will have seeds only when the trees are grown near certain other citrus varieties. The CVC page suggests that pummelo trees might be one source of pollen that will make Shiranui fruit seedy.

Should you plant a Shiranui mandarin tree?

From my homegrower’s perspective, the positives of Shiranui fruit are the flavor, lack of seeds, peelability, and large size. Or is the large size a negative? I actually wish the fruit were a little smaller.

The Shiranui tree is a strong grower and prolific fruiter.

In the context of my yard and the other mandarins I grow, Shiranui has earned a permanent place. It’s different from all the others in size and shape and flavor, and the tree is a reliable, fecund workhorse. What more can you ask for?

Where to buy a Shiranui mandarin tree?

You can find Shiranui trees at good nurseries in California. If they don’t have any in stock, ask them to order one for you.

Alternatively, order online. Two California nurseries that make Shiranui trees that I have experience with and can recommend are Four Winds Growers and Burchell Nursery (Tomorrow’s Harvest).

You can also make your own by ordering budwood from the Citrus Clonal Protection Program.

Here is a video profile of Shiranui:

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

I hope you find my Yard Posts helpful, and I appreciate your support so I can continue. Thank you.

I have a bluè berry plant from Rogers Garden. The top has died but the bottòm stock is thriving. Can i ģraft blueberry cuttings on to it?

Hi Greg,

Based on your post a few weeks back, I was down in Pt Loma today and scored 2 Shiranui trees from Walter Anderson Nursery there.. I got the last 15 gallon potted one they had and another sleeved one – they still have plenty of sleeves left.

Your Shiranui trees look great, I can’t wait to grow my own. I spend way too much money buying the Sumo oranges at the grocery stores 🙂

/Dave

Dave! I thought of you while writing this post and intended to ask you if you had gotten a Shiranui tree going at your place yet. Great to hear that you now do. You are going to love those trees.

Thanks Greg… yeah that whole pandemic thing got in the way of partnering on grafting those Shiranui back in 2020. What happened to the remaining Pixie branches as your Shiranui seems to have overtaken them?

The Shiranui I got at WA are standard sized, not semi dwarf, so they will get plenty big on their own some day. They are however around a bunch of other mandarins/tangerines so I hope they remain seedless. The sleeve is still in a pot so I could move it to a different spot to get away from pollinators if I needed to.

/Dave

Hi Dave,

The remaining Pixie branches are still growing as well as they always have. I’ve been pruning incrementally over the last couple years to allow the Shiranui to become about 60% of the canopy.

I am surprised!! it has good quality ripen. The neck like structures is also another eye traffic. Thank you for your amazing share!!

Hey Greg, I have a full size Navel tree and harvest hundreds by February. Which mandarin would you recommend as a compliment harvest wise? Shiranui or Gold Nugget if I were to only add one? Enjoy your posts thanks Greg.

Hi Dame,

This is a great question. I think I would go with Gold Nugget. I happen to have a Gold Nugget right next to my navel. The Gold Nuggets are ready as soon as the navels pass their peak in quality, sometime in March. And then the Gold Nuggets maintain good quality through spring, even into summer.

But I’m tentative on this because I don’t have a grip on how long the Shiranuis will hang with good quality. As of now, my observation is that they don’t hang as long as the Gold Nuggets, but maybe they’ll hang longer as my tree gets bigger.

Hi Greg,

I love your work! I have a couple questions, why are my lemon trees producing purple leaves, includes variegated eureka pink lemonade, Lisbon, and Santa Teresa? Also, do you do in person tutorials on grafting? I feel like I am missing a step and would like to become adequate at it. I don’t mind paying for a grafting tutorial session as well.

Shiranui Mandarin

Earliest to mature, please?

Hi Greg, Although they are supposed to be seedless, I have found some seeds in “Sumo Citrus.” Around 4 years ago, I germinated and planted the seeds. I now have 3 trees that are 4-6′ tall in pots in my house (I live in the Chicago area, and they summer outside). I have not yet gotten any blooms. Do you have advice on how to get to bloom, prune, and care for these with the hope that they fruit?

My Shiranui is shown as purchased in Greg’s article.

We are now coming up on one year since the article. My specimen is coming along nicely and we can see new growth beginning all along its length.

This of course reinforces my initial optimism about growing this delicious citrus fruit.

I’m desperately trying to find a shiranui mandarin to plant in Santa Barbara, but can’t find any available that will ship to California. Even willing to try some budwood but can’t find that either.

Any suggestions?

Hi Richard,

I see that Four Winds and Tomorrow’s Harvest currently don’t have any in stock. I would ask at a local nursery to see if they can order one from a supplier. Otherwise, sign up to be notified when Four Winds gets more in stock and check back with Tomorrow’s Harvest. I’ve seen some Shiranui trees at nurseries down in San Diego County lately so they’re around. I can’t recommend any other online suppliers, sorry.