Back in 2014, I wanted to plant some citrus trees along the north side of my driveway. I knew the varieties I wanted, and I envisioned planting about five trees that would ultimately grow into a citrus hedge.

But the hedge couldn’t get too wide or it would choke the driveway and entangle in our neighbor’s fence. It also couldn’t get too tall or it would block our view of the mountains although since our driveway went downhill, the lower trees could get taller than the trees planted closer to the house.

So I had my design parameters laid out.

Dwarf vs. Semi-dwarf

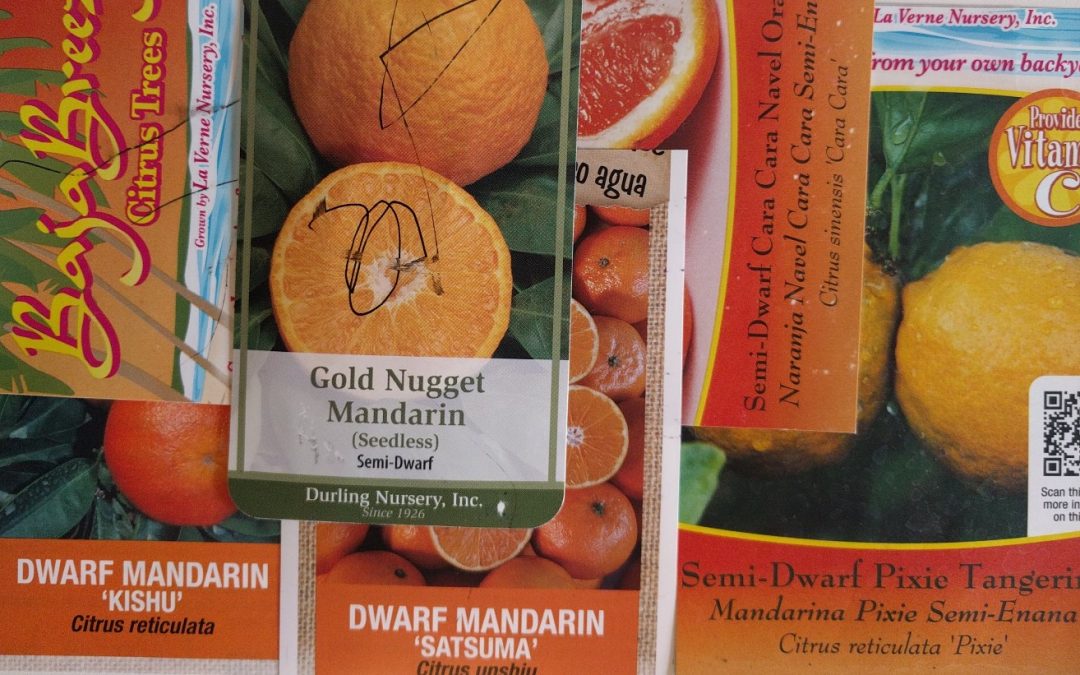

Then I went to buy the right trees. If you’ve shopped for a citrus tree recently, you know that they are always labeled with at least the two elements of variety and size. The variety might be Meyer lemon or Valencia orange or Rio Red grapefruit. And the size is usually described as dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard.

I knew that one variety I would plant was the Cara Cara navel orange, so I visited nurseries as well as a nearby Home Depot. One Cara Cara tree had a tag that said it was semi-dwarf and would mature at 10 feet tall. Another Cara Cara tree had a tag that said it was dwarf and would mature at 10 feet tall. Huh? Then what’s the difference between dwarf and semi-dwarf, if they both grow to 10 feet?

These two Cara Cara trees were grown by different nurseries, the dwarf by Durling and the semi-dwarf by La Verne. (Almost all citrus trees we buy in Southern California were grown by these two Southern California-based nurseries.) Maybe they just have different opinions of how tall dwarf is. The term is not regulated or standardized by the industry.

Dwarf vs. Dwarf

So what if we compare two different trees grown by the same nursery? Are they consistent in their use of the terms within the nursery? Another variety I wanted to plant along the driveway was a Kishu mandarin. (It is the best fruit tree for kids, as I wrote about here.) I found a Kishu grown by Durling and labeled dwarf. But the tag said it would only be 3-5 feet tall at maturity. Remember, the Cara Cara grown by Durling and labeled dwarf was said to reach 10 feet. One dwarf citrus tree will grow to 10 feet while another dwarf might get to 5 at most?

Variety vs. Variety

I was experienced enough with citrus in 2014 to know that, in general, orange trees grow bigger than mandarin trees. So maybe the terms were being used in a relative sense. In other words, a dwarf Cara Cara orange tree would still be bigger than a dwarf Kishu mandarin tree because orange trees are always relatively bigger than mandarin trees.

This made me think that I should pay more attention to the numbers on the tree tags rather than the terms dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard. How big did the tags estimate the trees would eventually reach? Numbers are objective. Disregard that the Cara Cara tree is labeled dwarf; only consider that its tag says it will grow to 10 feet. Ten feet is 10 feet. Or is it?

How citrus trees are made, in two short paragraphs

Almost all citrus trees you can buy are made up of two parts: the roots part and the top part, the rootstock and the scion. Usually, a seed is planted and a tree grows up for a year or so. Then a piece, called a bud, of another citrus tree is put onto that seedling tree. If we want to make a Nordmann Nagami kumquat tree, then we take a bud from a Nordmann Nagami tree and stick it onto the trunk of the seedling tree. The bud starts to grow.

The tree now has two parts: a branch of Nordmann Nagami kumquat (scion) growing out of a seedling tree (rootstock). Once the Nordmann Nagami kumquat branch is long enough, maybe a couple inches, the seedling tree is cut off above the kumquat branch. Now the whole top is Nordmann Nagami kumquat and only the trunk and roots are the seedling tree, scion on top and rootstock on bottom. Where the two were joined is called the bud or graft union.

(You must always remove branches that grow from below this graft union, as I wrote about in this post.)

(Watch a video of Don Durling budding a citrus tree here.)

What affects the ultimate size of a citrus tree

So our citrus trees have two parts that affect how big they will grow: the rootstock (roots) and the scion (variety on top). As I already mentioned, different citrus varieties naturally grow to different sizes. Orange trees grow bigger than mandarin trees, rootstock influence notwithstanding.

Rootstock influence

But the rootstock a citrus tree has also influences how big it will grow, how dwarfed it will be. I had been under the impression that when a nursery labeled its citrus trees dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard it was, at least in part, because they used various rootstocks that dwarfed the scion varieties more or less.

The varieties I ended up planting along my driveway were Satsuma, Kishu, and Gold Nugget mandarins, and a Cara Cara navel orange. So I called up the two nurseries that had grown my trees to ask what rootstocks they were on. (You can usually see which nursery grew your tree by reading the container, if it doesn’t say on the tree tag.)

I called Durling Nursery and asked which rootstock they used for mandarin trees labeled dwarf or semi-dwarf. “Trifoliate,” I was told. There are a few common trifoliates used, but one of the most common is Rubidoux trifoliate. And for trees labeled standard? “C-35.” The full name of that one is C-35 citrange.

Then I called La Verne Nursery and was told that they use C-35 for all of their citrus trees, whether labeled dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard.

That was curious. Same rootstock making dwarf and standard trees. Then what warrants the difference in labeling?

La Verne’s website explains, “We grow two different forms: one being a dwarf/semi-dwarf (bush / large shrub) style, and standard form (tree branches at 30 inches from the ground).” So they’re not saying they grow different sizes. They grow different forms. A tree labeled dwarf has been pruned at the nursery to look like a bush while they have pruned the standard ones to look like a tree, with a trunk and no low branching.

Beyond scion and rootstock

That accounts for the tree as you buy it from a nursery: it’s got the genetics of a certain scion and rootstock. Beyond rootstock and scion, there are many more factors at play which affect the size and speed of growth of a given citrus tree, and which might make a tree seem to betray its labeling.

In ground or container

The most consequential determinant of the size your citrus tree gets is whether you plant it in the ground or in a container because even the biggest pot you can buy will still constrict a citrus tree’s roots eventually. And if the tree’s roots can’t expand, then neither can the foliage. In this way, you can buy a citrus tree labeled anything, of any variety, and grown on any rootstock and reduce its size by growing it in a container.

Four Winds Growers up in northern California has made citrus trees in containers their corner of the market, and on their website they explain that a citrus tree in a container might reach 10 feet maximum while the same tree in the ground will become twice that size.

Soil depth and quality

On a similar note, soil depth and quality affect the growth rate and size of a citrus tree. In my own yard, I’ve got areas with deeper or shallower soil, as well as areas with rockier or richer soil. I’ve noticed citrus trees growing differently in each area.

Climate

A citrus tree might thrive and grow bigger in a hotter climate. Take the Gold Nugget mandarin, for example, which was bred by the University of California at Riverside. The University’s Gold Nugget Fact Sheet says, “Tree vigor varies somewhat by location. At southern desert locations (Coachella Valley) trees are quite vigorous with large canopy volumes. In contrast, at the cooler Santa Paula and Ojai (Ventura County) locations trees had significantly less canopy volume.”

We can think of other factors that will affect a tree’s growth too. How well is the tree watered? How much energy has it spent on fruiting rather than growing leaves and branches? Has it been nipped back by frost? How much sun is it growing in?

All this goes to say that it’s complicated, and though I felt frustrated by the lack of consistent, clear answers to how big the citrus trees I was looking to buy would get, upon further learning I felt sympathetic.

How to estimate a citrus tree’s mature size

I still had to figure out which trees to plant where along my driveway back in 2014. I approached that by finding multiple size estimates for each variety, including the ones on the tree tags, then doing some averaging of them, and then throwing in considerations for my particular soil and climate situation. I think this is the best, most realistic approach any home gardener can take.

For example, the Durling tag on the Gold Nugget mandarin tree I bought said the tree size would be 6-8 feet. Four Winds Growers said their Gold Nuggets got 8-10 feet. That landed me at a middle ground of 8 feet. So I ended up planting my Gold Nugget 10 feet from neighboring trees.

Down near the bottom of my driveway I have a few avocados, and above them I started with the Cara Cara navel orange because I guessed it would grow up to about 12 feet, then the Gold Nugget mandarin, then a Kishu mandarin that I figured would top out a bit under eight feet.

Just last year, I added another Kishu and a Satsuma mandarin, which I guessed would be smaller than the Kishu. But I might be proved wrong on this one. The Satsuma is already taller than the Kishu. Sure is exasperating trying to predict the growth of citrus trees! I keep my pruners at the ready.

You might also like to read my posts:

Hi Greg,

I really like your idea of citrus hedge. I hope to have similar approach on south facing cinder block fence, to help reduce the summer heat.

I planted CaraCara on dwarf rootstock in 2011, and wanted to keep in bush form about 4’ high. In 2014 it was 4’ and produced more fruit than wife and I could eat. Also I had to make sure I thinned the fruit at end of branches, especially before a good rain. To keep that height and shape I had to do moderate yearly pruning.

Robert

Hi Robert,

I wish I could fast forward ten years to see how my citrus hedge will turn out, but it’s doing well after four years now. Because they respond so well to pruning, I think citrus trees are ideal for hedges.

Can’t wait to have more Cara Caras than I can eat! Good tip on thinning fruit at branch tips. I’ll probably have to start doing that in a year or two.

Hi Greg

Thank you SO much for all your information! I want to plant at least 2 citrus trees and after reading your posts am thinking of Kishu, Cara Cara and Gold Nugget varieties. Is December a good time to plant or should I wait until the spring? I live in North Tustin.

Hi Susan,

I don’t think you’ll be disappointed with any of those varieties. It’s also a good threesome because Kishus start tasting good about now (my kids are going crazy about eating them right now), then Cara Caras after Christmas, then Gold Nuggets about March. That’s an extensive harvest window.

In North Tustin, you can plant citrus any time. I planted a new mandarin last month, and I’ve planted in January, and I’ve planted in summer. Only people who live in colder climates need to be more concerned about planting in spring. I find it easy to plant here in the cool times of year because you don’t have to stress about watering right after planting.

However, the disadvantage is that the trees just sit there. They don’t grow as soon as you plant them like they do in spring or summer. In fact, they might even turn their leaves a little yellow because of the cold soil. But you just have to trust that they’re going to come out of it eventually and green up and shoot up new growth.

One more disadvantage of fall/winter planting would be if your soil is clayey because it’s harder to find a window between storms where the soil can dry out for a week so that you can easily dig a planting hole. If I had clayey soil, I would probably wait until spring.

Thank you, thank you, thank you!!!!! I really appreciate you taking the time to respond- you are a BLESSING!

I found a online citrus tree selling website called https://www.citrus.com/. Have you heard of this website or have any experience buying from them? It looks like they can send everywhere but Texas and Arizona…..

Hi Daniel,

I hadn’t heard of this online citrus tree retailer. It looks like they are located in Florida.

Browsing their offerings and growing information, I’d recommend buying a citrus tree online from Four Winds Growers. Four Winds offers more and better varieties, and I have bought citrus from them and can vouch for the high quality and customer service.

Costco has a bunch of citrus on c-35 for $30. Do you recommend c-35 for SD Soil? Someone on Facebook mentioned an article that said c-35 doesn’t do well in high pH, high salt and clay soils.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318700705_C35_citrange_rootstock_-_a_complicated_story

Hi Eric,

Thanks for sharing that article. Citrus rootstocks sure are complicated. Moreover, as the article notes, the quality of the budwood used for the scion is also an important factor.

I have seen reports from the University of California stating that C35 is not good with navel oranges and in calcareous soil. Soils in San Diego County vary so I wouldn’t say C35 is good or not good overall for this area. I do know that my trees on C35 are mostly doing fine to excellent, but I don’t have them next to trees on a different rootstock but the same scion for comparison. My soil is about neutral pH and sandy loam.

I will also add that I have seen a yard in San Diego with many citrus trees on various rootstocks, and some are the same scion variety on different rootstocks; those trees perform differently and the fruit develops differently. That goes to say that rootstock does matter, for sure.

As a side note, a recent rootstock trial in the Central Valley found C35 to have the highest yields out of around 20 rootstocks with a Nules Clementine scion. Here’s the report.

Hi Greg,

Thanks for creating such a helpful resource for Southern California gardening! I’m contemplating a citrus hedge along a western facing side of my property. Due to surrounding buildings, the area only gets 4 or so hours of sunlight. Do you think citrus would work in a location like this?

Thanks,

Tyler

Hello Greg,

I just received a Semi-dwarf Cara Cara Navel tree as a gift. I am so excited to finally have a citrus tree however, I want to keep it in a pot for a few years until my husband and I buy a home. I was wondering if you have any growing in pot tips or recommends on where to research.

Hi Berlyn,

That’s a nice gift. I love Cara Caras, and the tree is so pretty; its foliage is among the prettiest of all my citrus. And mine is in full bloom right now and the bees are so happy about that.

People can get very opinionated about the best, perfect mix for citrus in containers, but I don’t think it’s so important what you put in there as long as you water properly. Anyway, Four Winds Growers has good advice on growing citrus in containers: https://www.fourwindsgrowers.com/pages/growing-dwarf-citrus

Also, there might be the option of putting your tree in the ground and then transplanting it when you move. I did this some years ago when I planted a Bearss lime tree in the ground and then dug it up and took it to my new house about a year later, and it transplanted fine.

Hi Greg

Thanks for the awesome info!

As a very beginner gardener with limited space, in SoCal, I’m looking for: a good variety of fruit trees I can grow easily in pots. Which are the best and smallest fruit trees and where can I buy them, ideally around San Diego? Eg I’d like one-two of each, say, lime, lemon, apple, a pomegranate, an orange, a peach, plum pear nectarine, maybe those hybrids, idk if exotics like guava persimmons cherimoyas come in dwarf etc. also is there anywhere local to buy Alphonso mango trees? I’m looking for the sweetest best fruits that grow in pots.

Thanks in advance

I hope he answers, I’d love to know what the best nurseries here in SD county are for all those fruits you listed. I’m wanting to create a mini orchard here in Vista=)

Hi Megan,

If you’re in Vista, you’re in the heart of nurseryland. There are so many good nurseries all around you. Most of them are best stocked in certain types of fruit trees though. Let me know if there are any specific types you’re looking for.

Hi Sharmila,

Technically, you can grow any fruit tree in a pot. But if you hope to get a bunch of fruit from the tree, you’ll likely find it quite the challenge with certain types unless your pots are very big. For example, I’m guessing a persimmon would require a very big pot in order to produce much more than a couple persimmons.

On the other hand, limes and lemons are easy to grow in a pot and get ample fruit.

You can check at your local nursery to see if La Verne Nursery (a wholesale grower) is selling Alphonso trees this year. The local retail nursery could then order one for you. But I have heard that that variety doesn’t do great in Southern California compared to some others. I have no personal experience growing it though.

Hi Greg,

My life dream is to grow oranges on the 10 acres of sandy loan soil I own in the Bitterroot Valley ,Montana.I know this is going to require overcoming some unique challenges and will be grown in greenhouses like this:

https://greenhouseinthesnow.com/greenhouse-kits

I want to turn this into a viable commercial operation or at least demonstrate that it can be done.

Can you give me any suggestions about variety and size.

I am interested in trees that will set and bear fruit sooner than later and high quality fruit.

Have you any thoughts on this or can you point me in the right direction?

Thanks for your time.

Gary

gsnookolds@gmail.com

Hi Gary,

I’m going to point you to the Citrus Discussions on the Tropical Fruit Forum: https://tropicalfruitforum.com/index.php?board=12.0

There are many participants who grow citrus in similar climates: Colorado, Pennsylvania, Eastern Europe.

There is a lot of firsthand experience for you to read and nice growers who can answer questions.

Hello,

I’m real irritated right now because I didn’t look closely at the labels on the packs of flowers and the potted hydrangeas I bought in the spring. It’s only after they’ve been in the ground for a while that I discovered everything was labeled as “dwarf” and so I’ve got these pathetic plants and shrubs where I’d expected large one’s. I view this as an attempt by nurseries to make more money by cheating you on the size plants available, and it makes me angry, mad and disgusted!!!! I’m not even sure Lows even sells full sized plants anymore.

I have a semi-dwarf orange plant(orange midnight seedless) which is now close to1metre high and I thought it was thriving, until today. There was plenty of white buds on the tree which I thought were potentially fruit. These have now basically dropped off,leaving the tree rather denuded of fruit. I live in the southwest of WA(Bunbury). The weather is beginning to cool after a long spell of hot to mild days. Is there a plausible reason for this loss of buds and if so, what can I do to rectify the situation and get back to having a healthy tree. Thank you for your attention. Barry

Thank you so much for all of the great info, you’re such a great resource! I would to get some advice if you’d spare the time. I recently purchased 4 STD trees for our side yard ( 10’x 60’ ) Washington Navel, Valencia, Eureka Lemon, Cara Cara. Turned out the Cara Cara was actually a SD. I was worried to have it look strange as the only SD in the row, but have struggled for weeks to find a STD Cara Cara in 15 gallon like the other 3. I returned the SD Cara Cara, but can’t find anything but SD elsewhere over 3 counties. The 3 STD trees are layed out but not planted yet. Would you just go with the SD? Would it be so different, look out of place?