In 1956, when Bob Bergh began developing new varieties at the University of California, Fuerte was the most popular avocado in California.

Frustrating for farmers, some Fuerte trees were fruitful whereas others were not. And Fuerte trees made more avocados in certain locations and in certain weather. “Erratic,” was the term most often used to describe the variety. So in an improved avocado, Bergh was looking for “a Fuerte that bears dependably,” as he wrote in 1961.

There was this up-and-coming variety at the time called Hass. It was more regularly productive than Fuerte and its fruit inside was delectable, all agreed. However, as one farmer put it in 1965, “its well known drawback is its black and warty surface.”

Black is the color of rot on an avocado. Eaters didn’t want to see black. They wanted fresh, they wanted quality, they wanted green, like Fuerte.

Within this context Bergh selected the variety that he would name after his wife, Gwen. He had found a tree more dependably productive than Fuerte and a fruit as delectable inside as Hass but whose skin remained green. After securing a patent, Bergh released the Gwen variety to the world in 1984.

Before continuing the story of Gwen’s development, let’s look at the variety’s fruit and tree characteristics.

Gwen avocado fruit

From the outside, Gwen can be hard to distinguish from Hass if both fruit are freshly picked from the tree before the skin of Hass blushes black.

But the subtle differences are that Gwen is a bit rounder, has smaller, sharper bumps on its skin, and has a smaller stem (pedicel) that is more centered.

Upon ripening, a mature Hass turns completely black whereas a Gwen remains green.

Inside, the flesh of a Gwen is slightly pale, usually not as golden yellow as Hass.

Never are there fibers in a Gwen.

When you peel a Gwen, the flesh separates cleanly, similar to Reed.

Noting this might sound pedantic, but it isn’t to a chef – nor to my kids. I often serve them wedges of avocado with a meal, and they enjoy the wedges most when its a variety that peels cleanly. Gwen and Reed are among the best here. GEM and Hellen are other varieties that peel cleanly.

The skin is stiffer on Gwen compared to Hass; this helps it peel and not break into pieces.

Related to Gwen’s skin, when it was in testing, the Gwen variety was called T225. That’s because it was the 225th Thille seed that Bob Bergh and his assistants had planted. (See my profile of the Thille variety here.) And Gwen has skin a bit thicker and stiffer than Hass, resembling Thille’s.

Also similar to Thille, the seed of Gwen is, on average, larger than the seed of Hass.

The flesh of Gwen is dense, meaty, and never watery or mushy like some varieties can be, especially in the early part of their season or when they are over-ripe (examples are Sir-Prize and Bacon). It has a drier feel in the mouth compared to Hass.

The flavor of Gwen is similar to Hass but often a hint richer, nuttier, even in the early part of its harvest season.

Harvest season

When is the Gwen harvest season? June and July is the peak in my inland Southern California location. For comparison, May and June is peak season for my Hass.

Yet, I have picked Gwens worth eating as early as February, and I have eaten good-tasting Gwens as late as October.

But because Gwen’s skin is stiff, it shrivels at the top when it ripens if picked earlier than about April. While the flesh inside may taste fine, the skin shrivel is not attractive.

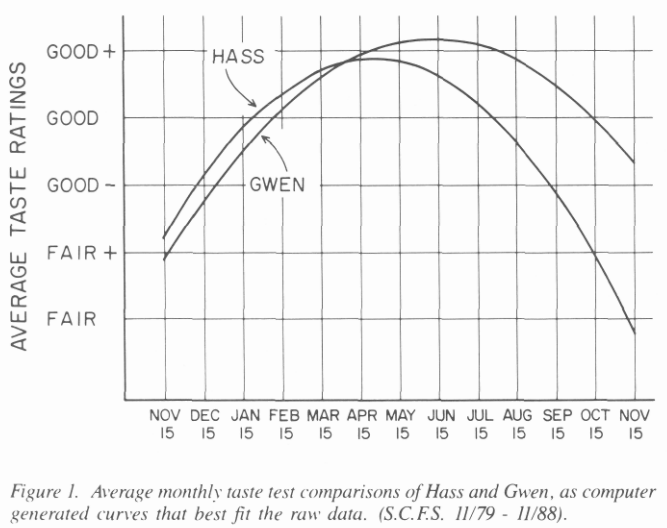

“Determining the Optimum Time to Pick Gwen” is an excellent article written by Bob Bergh and Gray Martin for the 1988 Yearbook of the California Avocado Society. Within the article is this graph showing the results of 74 taste tests done over a ten-year period in Irvine, Orange County, where Gwen and Hass were compared:

It shows how long the tail of Gwen’s harvest season is. Though Hass is famous for having good hang time and keeping its quality on the tree for many months, Gwen does so for even longer. The graph results show Hass being rated good for six months, but Gwen is rated good for eight.

Gwen tree flowering and fruitfulness

Does a Gwen tree make a lot of avocados? It certainly can. Gwen’s fruitfulness was one of the reasons it was selected from the thousands of seeds that Bergh planted.

At different times, Bergh estimated that a grove of Gwen trees would produce twice as many pounds per acre (1982) up to more than seven times as many pounds per acre (1988) compared to Hass. And Hass is a good fruiter.

What I can say from my own experience is that mature Gwen trees indeed make a lot of avocados. This tree in Redlands, for example, I have harvested over the span of many years, and it typically carries about 1,000 avocados in a heavy year down to about 300 in a light year.

Gwen likes to make fruit in clusters.

Gwen is of the flower type called “A.” This does not mean that it needs an avocado tree of the flower type called “B” nearby; I have seen lone Gwen trees fruit well. Also, read here about the Earhart Grove of Gwen trees that produced very well with no B types nearby.

It never hurts to have mixed varieties in proximity though. And Bergh did an experiment that showed that Gwen will produce even more if a different variety is nearby. I have seen numerous Gwen trees exceptionally full of fruit when near Fuerte trees.

Gwen tree growth and architecture

For an avocado, Gwen trees grow upright. They are similar to Zutano and Reed in this habit.

Once their branches are holding fruit, though, they cascade down from the weight. So the older a Gwen tree gets, the wider it becomes. Yet Gwens never spread as much as Hass. They always maintain a narrower footprint.

And after a handful of years, Gwen’s tree architecture becomes very suitable for growing in hot-summer locations because it cloaks most of its avocados within a layer of foliage. Its canopy becomes dense and its fruit mostly hides safely inside. This is similar to the varieties Lamb and GEM. This is dissimilar to the varieties Hass and Ardith and Pinkerton, whose canopies are more open and whose avocados are therefore more vulnerable to sunburn.

Gwen foliage has nothing distinctive to mention. Still, here is a close-up of some Gwen leaves:

Strengths and weaknesses

The main weakness of Gwen is that it fruits too much at a young age. You often have to remove some of the avocados on a young Gwen tree because it will try to carry more fruit than its small frame can handle. And some young Gwen trees will even drop all of their leaves as they flower profusely.

Even once a Gwen tree is up to fruiting size, say five feet tall, it might still make more fruit than you should let it carry. If such fruit, especially fruit that is at the top of a tree, is not thinned, then the branches and fruit will likely be sunburned. See this example:

Gwen’s main weakness is simultaneously its main strength. Gwen’s insistence on flowering and fruiting on young branches does not stop as the tree as a whole ages. Because of this, a Gwen tree that is pruned one spring will grow back and make abundant flowers and fruit on the new growth the following spring. This is an advantage if you want to keep the tree down in size. And not all avocado varieties have this characteristic of precocity.

In terms of cold tolerance, I have not seen any clear difference between Gwen and Hass.

Is Gwen a good fit for your yard?

If you have a small space, Gwen is preferable over Hass. It’s easier to keep a Gwen tree’s canopy down in size because it grows more slowly and it fruits more quickly after pruning.

For example, this Gwen tree in Fallbrook is around 40 years old, having been grafted onto a mature rootstock in the 1980’s. The owner keeps it “petite,” as she likes to say: about 12-feet by 12-feet. And it makes loads of fruit.

If you would like to grow an avocado tree in a container, Gwen is a good choice. In fact, Bob Bergh and his assistants Bob Whitsell and Gray Martin once reported on a Gwen tree that they had kept in a container for 16 years. They had pruned it very little, but still it was only “15 feet tall with about 12 feet spread at its widest.”

If you prefer green over black avocados, Gwen is a good alternative to Hass or GEM.

Gwen can fit the spring-into-summer harvest window in a grouping of avocado trees that will provide nearly year-round fruit. For example, once when asked for variety recommendations to get a year-round harvest, Reuben Hofshi, founder of AvocadoSource, said, “Maybe you can plant 4 trees: Mexicola, Fuerte, Gwen, and Reed. This will cover most of the year with great eating fruit.”

Keep in mind that young Gwen trees are sometimes fussy and require extra attention compared to Hass.

For me, I have two Gwens in the ground in my yard. One I purchased and planted to mark the birth of my daughter in 2017. The other I created myself in 2019 by sprouting a Gwen seed to use as a rootstock and then grafting a Gwen scion from my daughter’s tree on top.

Gwen variety development

Between 1956, when Bergh began searching for “a Fuerte that bears dependably,” and 1984, when Bergh at last presented Gwen, the avocado world had changed. The green Fuerte was no longer the most popular variety, the black Hass was.

The middlemen known as marketers, handlers, and packers (those who buy avocados from farmers and sell to grocery stores, restaurants, etc.) had spent time and money helping consumers get used to the black peel of Hass. More importantly, they envisioned the future as a one-variety market, a commodity market, where all avocados were Hass and only Hass. “A monoculture is a marketer’s dream,” I once heard an avocado marketer say.

Ironically, in the end, it was the black peel of Hass that became its desirable quality. During the harvest, storage, and shipping processes, Hass avocados can be thrown around like rocks and the darkening peel will hide the bruises. Not so with a green avocado.

Green avocados benefit consumers; black avocados benefit producers. Of this, Bergh was well aware. In a 1988 article he and Martin wrote that Gwen’s green skin “permits detection of any rot spots. Many consumers have unwittingly purchased partly rotted Hass fruit.”

So Bob Bergh had discovered this splendid avocado variety, but the industry wasn’t going to buy in. There was a short-lived Gwen Growers Association formed in 1987 to promote the variety and serve as a source of information for farmers, and around 600 acres of Gwen trees, mostly in San Diego County, arose. But Hass had already become The Chosen One. Gwen’s commercial future was doomed.

(Read more about this in my post, “What happened to the Gwen avocado?”)

Here is a curiosity to consider: Almost all farms in California that once grew Gwen trees have removed them or grafted them over to Hass; on the other hand, I’ve never seen or even heard of a home grower who has abandoned a mature Gwen tree.

Legacy

Bob Bergh (and Gray Martin) didn’t give up. He simply started using Gwen as a source of seed to find a black-skinned avocado that could out-Hass Hass.

From a Gwen seed came the variety called Lamb/Hass, for example, a tree that makes fruit that looks a lot like Hass but which has a later harvest season.

From a Gwen seed came the variety GEM, a tree that makes fruit that looks a lot like Hass but which is more efficient than Hass in that it makes more fruit per cubic foot of tree canopy. (See my post here about GEM’s efficiency.)

From a Gwen seed came the variety Luna (formerly BL516/Marvel), a tree that makes fruit that looks a lot like Hass but which has a B-type flower so it can be used to potentially increase the yield of Hass trees near it.

Gwen is a fine avocado and tree in her own right, and a good mother too.

Video profile of Gwen avocado

Video profile of Gwen avocado tree

More avocado variety profiles are here.

My Yard Posts are categorized and listed here.

Thank you for your support of my Yard Posts so I can keep them coming and without ads.

Greg, I bought a Hass & Gwen 5 gallon trees in 1986 from Tom Spillman at La Verne Nursery when they were in San Dimas. My Gwen’s fruit are normally ready to harvest in March. About 1 month after Hass which is planted 20’ apart here in Rancho Cucamonga. GEM reminds me of Gwen in terms of young trees producing lots of fruit, and continuing that as mature trees. My Gwen has always out produced my Hass tree in quantity of fruit. I have tasted my Home grown Hass, GEM, and Gwen at Peak Time which was April 2023 , and I chose Gwen. Thank You for the article, really enjoyed it!

Thanks for sharing this, David. Great to hear from you. Yours is a testimony to be listened to.

I recently bought a Gwen and a Gem together. They arrived just about 28 inches tall, good architecture, healthy leaves. I planted them right away in 15 gallon containers filled with perlite, sand, decomposed granite and a little peat moss and quality planting mix. A little over a month now and they’re both doing well, but the Gwen has grown 8 inches while the Gem’s buds are just beginning to fill out. I’m in Humboldt (9a/b) temps now averaging about upper 60’s/low 50’s. My only other avocado that’s grown this fast is a Bonny Dune but it took a year before it took off. Is this typical?

Hi Larry,

Good to hear that your new Gwen is doing well. I look forward to future updates on it.

The differences in growth between the Gwen, GEM, and Bonny Doon are due to the scion varieties and some other factors, but a significant one that can’t be overlooked is rootstock. My guess is that they’re all on seedling rootstocks, most likely Zutano. Seedlings are always a bit variable.

By the way, your high temps now are upper 60’s?! What a different climate compared to mine, where it was 100 two days ago and rare is the day under 90 in summer. Shows how misleading USDA zones can be if you don’t know that they are only based on average low temperatures in winter. My location is also classified as 9b.

I didn’t know USDA based their zones on winter. Interesting. Our winter lows seldom go below 30 and usually in the mid to low 40’s with occasional weird days it will get to upper 60’s or two or three times maybe 29 for a few hours. Last winter was a little warmer than usual – All my trees came through with lots of new growth and no damage including a Lamb, Reed, Gem, Sharwil, Carman and a Pinkerton. I’m hoping a few of the Lamb’s B.B.’w will make it to maturity.

Thank you for your posts. I often refer to them. I’m a member of an online Avocado group and we get questions from around the world which i often refer to you. Keep up the good work..

Hello Greg, you may remember that my new Gwen was struggling after we planted her along w a Fuerte and Lamb. (Or you may not, haha.) Well she recovered from whatever was holding her growth back initially and is doing great after I stripped off the first bbs set on all the new trees. She has grown about 3 feet since I raised her issue here, and set a ton of fruit. I’ve sought out a Gwen for years since a local farmer recommended her, and I saw your videos. I’m v excited.

Additional note: Our climate in fillmore tends to extreme—both cooler in winter and hotter in summer. We’ve noticed the bacon tree withstands the sunshine abuse much better than the hass. That’s a positive for those who need a variety that can withstand punishment. The bacons are tasty enough for us.

I live in Cupertino, California. Where can I buy Gwen avocado tree? Thank you.

Hi Arlene,

Four Winds Growers in Watsonville often has Gwen avocado trees available: http://fourwindsgrowers.com/products/gwen-avocado-tree?variant=21362766938171

Hi Greg,

Question, please: Do you recommend pruning up the skirts of avocado trees? If so, at what point in the trees’ growth should one do so? I have a Lamb Hass, a Reed and an ever-struggling Sharwil (heat and humidity), if it matters.

Thanks much,

Cara in Pasadena (Eaton Fire survivor)

Hi Cara,

Great to hear that you made it through that fire.

This is a question without a simple answer, of course! My rules of thumb related to skirting avocado trees are:

1. No branches emanating from the trunk below knee height.

2. No branches touching the ground once the tree is big enough to carry a crop. (That is about 5-6 feet tall.) Before then, let any branches weep onto ground because they retain mulch and shade trunk and rootzone.

3. Skirt as necessary to prevent sprinkler irrigation interference.

4. Never skirt so high that direct sunlight hits trunk. (This prevents sunburn.)

Some of this info is dealt with in my post on training avocado trees: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/training-young-avocado-trees/

What are the space between two avocados?

Thanks for the write up. Unfortunately I am out of room to add a Gwen to the mix.

Love my gwen tree. I read all the info youve provided on your other write up. It def needs to babied a bit because of its heavy flowering and fruit set but it worth it for the production. Ive seen other owners who dont thin it out when the tree is young and branches break.

Hello Greg,

I have a three year old Reed avocado tree that has put on a lot of new growth and has some young fruit. Today I noticed that the tree has some yellow leaves (bright yellow) with green spots on them. I am wondering what this is and what I need to do about it.

Thank you, Ellen

Hi Ellen,

I’m wondering if you are seeing senescing leaves. See a photo of senescing leaves on my Reed tree in this post: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/reading-avocado-leaves/