No less an authority on avocado varieties than Oliver Atkins wrote in 1978 that Pinkerton “appears to be the best variety we have come up with for California since the Hass.” Why then, over the ensuing 44 years, have most of us in California never eaten a Pinkerton avocado?

While I don’t have a precise answer, this post will touch on some reasons as I aim to answer another, more important, question: Is Pinkerton a good avocado variety to plant in your yard?

Fruit characteristics

First let’s look at the fruit. Pinkertons are “necky.” In other words, they have an elongated pear shape rather than a round or egg shape. And in some years in some locations, Pinkerton avocados can look extremely stretched out.

Fortunately, the flesh inside a Pinkerton’s neck is solid. This is unlike the Don Gillogly variety, for example, which has a seed cavity inside extending up its neck.

Pinkertons are larger than Hass, but more than that they have a very small seed, meaning you get more flesh to eat in any given avocado.

The flesh has a fine texture and no fibers to speak of. It has a pleasant yellow to green color, and the taste is mildly nutty, very pleasing.

The skin of Pinkerton is a similar green to an unripe Hass and is about as bumpy as Hass, but the Pinkerton’s bumps are sharper. As a Pinkerton avocado ripens, its skin remains green. The skin is a bit thinner than that of Hass.

The skin peels off the flesh of a Pinkerton acceptably sometimes but not always.

Occasionally, a Pinkerton avocado develops a black spot near its bottom end, and this deterioration affects the flesh inside in that area. It’s not as common an occurrence as on some varieties such as Bacon, however.

The main peculiarity of Pinkerton is that it takes two to three weeks for the avocado to ripen from the time it is harvested. This can test one’s patience. Moreover, it can be tricky to judge when a Pinkerton avocado is fully ripe since it softens in the neck before the base. You have to wait to cut it open only when both the neck and base feel ripened.

Variety history

Pinkerton’s long ripening time was thought to be of benefit when the variety began being test-grown by farmers because it would allow them to ship the fruit long distances.

According to accounts in the California Avocado Society Yearbook of 1978, the variety was discovered by John Pinkerton, who found the seedling growing among Hass, Edranol, Corona, and Rincon trees on his ranch in Saticoy, Ventura County, in the early 1960s. The seedling bore consistent crops of high quality fruit so he grafted wood from it onto three older trees near his office, where he could watch them. He evaluated these trees for a number of years until he was convinced that the variety had commercial potential. In 1975, he received a plant patent on the Pinkerton avocado. Sadly, only three years later, John Pinkerton passed away.

One hope for Pinkerton was that it would, as Oliver Atkins put it, “help fill the void caused by the declining Fuerte acreage and, as it ripens and sizes ahead of the Hass, should tend to stop growers from picking Hass too early.” (CAS Yearbook, 1981)

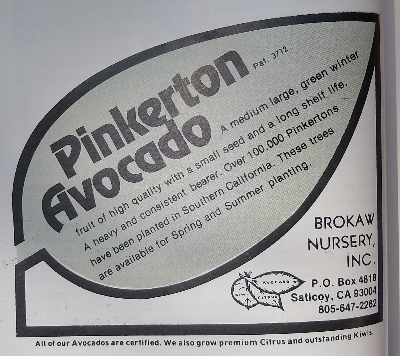

In 1982, Brokaw Nursery (also located in Saticoy) ran this advertisement for Pinkerton in that year’s California Avocado Society Yearbook:

Frank Koch, writing in his 1983 book Avocado Grower’s Handbook, quoted one of Pinkerton’s early supporters (Warren Currier) as pointing out that Pinkerton trees seem to have “much greater limb strength and tolerate winds better than most other varieties.” This has proven true over the decades. On the other hand, Currier claimed that Pinkerton was less alternate bearing than Hass, which has not proven true in my experience. All of the mature Pinkerton trees that I know have clear “on” years and “off” years.

By 1984, weaknesses of Pinkerton, especially from the perspective of a commercial grower, had become obvious. Bob Bergh, director of the avocado breeding program at University of California, Riverside, listed these imperfections in an all-around fascinating article in the California Avocado Society Yearbook called “Avocado Varieties for California.” They included the fact that Pinkerton trees fluctuated in their production just like Hass as they got older. Also, Pinkerton had a “shorter harvest season than Fuerte;” the Pinkerton fruit “sometimes have hard-spot ripening problems;” and some fruits “tend to become too large” and have “too pronounced neck development.”

In 1989, Hank Brokaw (of Brokaw Nursery) wrote about the challenges of introducing the new Pinkerton variety. Brokaw had planted a few thousand acres of Pinkertons, but found that the slow-ripening of Pinkertons was now seen as a disadvantage since retailers wanted fast turnover, and handlers (companies who buy avocados from farmers and sell to distributors and retailers) complained that Pinkertons “couldn’t be stored under refrigeration.”

As a commercial variety, Pinkerton did not fit into the new marketing and supply chain trends of that era, and not long after, most farmers in California gave up on the variety.

Home growers continue to plant it though, in part because the tree is slightly smaller than Hass and many other varieties.

Tree characteristics and bearing habit

Pinkerton avocado trees end up shaped much like an orange tree, with a domey, spreading form. And they take this shape for similar reasons to an orange. In one year, branches will grow upright, and then flower.

Then the tree sets lots of fruit, and the weight of the fruit bends the branches down.

The next year all of that fruit is harvested, the tree grows more upright branches, then blooms heavily the following spring and the process repeats.

The leaves of Pinkertons often have margins that undulate.

The flowers of Pinkerton behave in the “A” fashion.

Pinkertons tend to set much of their fruit in clusters rather than being distributed evenly throughout the canopy. They set fruit in clusters especially during years when they have few fruit on the tree overall.

This is similar to some other varieties, such as Gwen. However, unlike Gwen, once new fruit has set on Pinkerton most of it holds all the way until maturity.

Pinkerton starts fruiting at a young age, too. The first Pinkerton tree I ever planted was in a five-gallon container and already holding a nice sized avocado. Here’s one in a three-gallon sleeve holding two young fruit:

Pinkerton’s precocity has been used by breeders such as Bob Bergh, who wrote: “Seedlings [start bearing] in maybe the fifth or sixth year and more in the eighth and ninth year . . . Seedlings of ‘Pinkerton’ have the remarkable ability to start bearing the second year from planting.”

In addition to bearing fruit at a young age, Pinkerton out yields many varieties overall. An avocado farmer in South Africa, where Pinkertons are a more common commercial variety than here in California, once told me that Pinkertons were by far his most productive variety.

In need of a pollenizer

Pinkerton’s high productivity only comes when another kind of avocado tree is growing nearby though, in my experience and in the experience of others (see Gad Ish-Am’s comments here).

I planted a Pinkerton tree in 2016 that bore a few fruit each year until the spring of 2021 when an Edranol I planted beside it first bloomed. The Pinkerton had few flowers itself that spring but still yielded 29 avocados from its six-foot diameter canopy. (It had only yielded six avocados in the previous five years combined, when it had no pollenizer nearby.)

Which varieties pollenize Pinkerton well? Other than Edranol, I’ve personally seen evidence that Fuerte, Bacon, and Sir-Prize work. I’ve also read that Ettinger does (see “The Israeli Ways”).

Cold and heat tolerance

Unfortunately, I have grown Pinkerton for nine years in a location that often gets too cold and too hot for avocados generally. Fortunately, this has given me a chance to observe firsthand the variety’s limits.

As for cold tolerance, Pinkerton is roughly equal to Hass. It is not a variety that tolerates cold better than others that we commonly grow in California.

As for heat tolerance, Pinkerton leaves and limbs get sunburned in high heat more than many other varieties, but this is partly because they often carry heavy loads of fruit that expose the canopy to the sun. In this way, Pinkerton is weak in the heat. However, Pinkerton is strong in the heat in that it does not drop its fruit as much as other varieties. (See details in my post, “Heat tolerance of avocado varieties.”)

Harvest season

The main harvest season for Pinkerton starts in March. I’ve picked them in January and February, when they can ripen and taste acceptable, but only in March do they start to reach their potential.

Though commercial growers of yesteryear tried to market Pinkerton as a winter fruit, the main crop of Pinkerton is rightly considered a late winter / early spring avocado. In fact, in the 1989 article by Hank Brokaw mentioned earlier, Brokaw says that John Pinkerton’s ranch foreman originally told him that the Pinkerton avocado “matured about April.” Growers were just trying to market Pinkertons earlier in order to avoid competing with Hass, which also matures about April.

That being said, Pinkerton blooms earlier than many varieties (including Hass), and in some locations it will start flowering as early as October. Any fruit that sets there in the fall will ripen beginning around the following fall. But even with Pinkerton’s early bloom, it still tends to actually set most of its fruit during the later months of bloom (March, April, even May).

I’ve eaten Pinkerton as late as July, but I’d say that high quality Pinkerton fruit from a tree in Southern California is not likely to be picked past May or maybe into June.

In this video I profile the Pinkerton avocado using a late-season fruit:

Is Pinkerton a good fit for your yard?

Pinkerton is an avocado variety worth growing if you want a collection of a handful or more varieties in your yard. It is not a good choice for a yard that can only fit one avocado tree unless neighbors have other avocado trees that can provide pollen for your Pinkerton.

The ideal yard for a Pinkerton is one in which there is space for more than a single avocado tree (because of its need for a pollenizer). For example, here is a lineup of three avocado trees in a front yard with Fuerte, Bacon, and Pinkerton:

Finally, here is a video profile on the Pinkerton avocado tree:

All of my avocado variety profiles are listed HERE

All of my Yard Posts are listed HERE

Thanks for (all) of your commentaries. I have 6 avos (hass + Fuerte) growing in the yard. 3 are on a side hill, (and require lots of watering). The soil here is mostly decomposed granite, with some veins of clay in the yard. I use Triple 16 for fertilizer on the trees.

We were hit hard by the Santa Anna winds and heat in 2020 and all of the trees, except for the fuerte, were hit hard with the one week of high heat. The trees have finally come back, after being pruned back after the limbs were burned. (I painted with white latex paint, on the exposed bark to help). The furete and hass have come back beautifully, and are all full of blooms. I’m still picking a few furte, but are almost finished. Question, the fuerte is the only tree that shows brown leaves (on the sunny side). I take it that this is from the salts in our water supply here in Southern Cal. What can be done to help counter it? The tree isn’t in distress, but everyone makes comments about the leaves, (saying that I don’t water enough). My water bills say, NOT!

Hi John,

Thanks. I’ve got a few trees that have a lot of leaf burn right now too. It does seem to be all about the water. I just didn’t water them enough last year. As I travel around, I notice that growers who water “too much” have trees that look gorgeous this time of year. I’ve already started upping the water to some of my trees to correct my mistake and hopefully I’ll see results this time next year — with not only better looking trees but also more fruitful ones!

Thwnks. We had some great rain in early March, so I watered the avos hoping that the rain fall would help leach the salts from the (city water).

The leaves began to look better as the new blossoms started coming ion the trees.

It could be that I [really], need more watering. The water bills are (killer) but the end result may, just be an excellent ftuit season for us. The higher end avocados are running about $3 and up, in the local markets. Organic (large) fruit may fetch $4 each.

The water companies are killing the avo market in Southern Cal. A SAD epitaph for the Avo Hub of the West Coast. Thanks for your columns.

Indeed Avocados 🥑 do love much water

I’ve got one Pinkerton left hanging on the tree. It’s exceptionally good fruit.

I noticed that the tree held most of its leaves this winter which was a pleasant surprise given how avocados lose them so much that time of year. Ours is mid to late bloom and there’s quite a bit of fruit setting. I’m hopeful fruit drop won’t be too bad in a couple of months.

Hi Bob,

Those are good signs. If an avocado tree blooms a lot while holding onto many healthy leaves, you’ve reached the gold standard. Nice work.

Thank you. The Stewart held even more leaves than the Pinkerton. My fuerte lost almost all of them but the lamb hass I wrote off for dead seems to have come roaring back to life. I must admit, I’m probably an over waterer. I’ve been using fish pond water to supplement the regular waterings and I think that’s done wonders. The Stewart and Pinkerton are right next to a heavily watered lawn and I think that’s part of it too.

My grandson was working for a (Fallbrook) grove owner, that had acreage in Oceanside, and a second 5 acre grove in Fallbrook. At his suggestion, I purchased a Pinkerton tree about two years ago. I planted it maybe too close) to a mature Hass tree on the side hill of our small property.

I also have Fuerte about 25 feet away. Because we have been lacking in a bee population in the yard, I have several roses, honey suckle, star jasmine, 3 orange trees and plum trees, as well, to try to bring more bees in to help with Pollinizing of the trees. That hasn’t helped much but having just gone thru a few summers of very hot days and Santana winds, the bees are still scarce here. I’ve thought about bringing some bee hives, but it’s a bit expensive for only 7 fruiting trees. The neighbors don’t seem to want to grow any fruit in their yards.

Had I known about the long period required for ripening Pinkertons, I think I would have opted for another Hass. (So, I just did that.) Low and behold, after only one year in the ground, the Pinkerton was hiding “one” fruit for it’s first year.

I guess I’m just going to have to get used to $300 (monthly), water bills with Fallbrook Public Utility Company.

The water seems to be a greater factor for a good harvest.

After a poor harvest for two years, my older Fuerte has really done well for itself.

P.S. The prices of fertilizer has tripled in two years. Yikes.

I guess most of it comes from China. (what did we expect)?

My Hass avocado (year 3 in the ground coming from a 5 gal container) has finally started to flower, and boy did it flower like crazy. At the same time more than half of the leaves dropped, which scared the hell out of me until I read your post here 🙂 Weird thing is that nearly of the leaves that dropped came from the top half part of the plant. Branches look healthy, no die backs, and there’s actually new leaf growth emerging.

I’ve planted a Sir Prize and Kona Sharwil this past winter and will be on the lookout for a Pinkerton. What other varieties would you recommend?

Thanks for such a comprehensive write-up on the Pinkerton, Greg.

Great write up on Pinkerton. It compels me to replace my small Pinkerton that died this winter on one of those really cold nights that I didn’t see coming. This article also increased my curiosity about Gwen: Why don’t I hear more about Gwen? Nutty, excellent flavor, and highly productive. Sounds like a winner.

Great question, Walter. I’ve asked it myself many times without finding a totally satisfactory answer. I’ll tell you what I know in a Gwen profile post soon — within the next two months.

Greg, I have 2 Pinkerton trees that bloom and lose most if not all of its leaves. A lot of the blooms fall off and turn brown and both trees lose a lot of the leaves as most others do but with my Pinkerton’s they lose almost every leave. The first year I thought this was due to some grasshoppers that at almost everything off the tree but its happening again this spring. Any idea what I am doing wrong ?I water them both on the same schedule .

thanks again for all the helpful information and insights – really helps me be a better gardener and helps me help others better.

Hi Philip,

Are the trees setting fruit too? It’s OK if the trees shed their old leaves this time of year as they bloom and also grow new leaves, but if they’re not setting fruit then you might have a pollenizer problem or a watering problem.

I have 2 Pinkerton trees both came from 15 gallon pots and have been in the ground since. Both shed all of their leaves and are bare each year. One was being attacked by aphids- my only tree if 10. The other browns before the flower and then they fall off. I took some pictures but can attached them.

Thank you for all your knowledge- it really helps a lot.

Hi Greg — I was looking at some of your posts from a few years ago and you mentioned planting 3 avocado trees in one hole/very close to each other. Just curious how that is going, because I have a very small yard space that I’m looking to plant a Hass and Reed in, but I’m really itching to put in a third! Just wondering how your experiment worked out 🙂

Hi Gene,

I think you’re referring to this post: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/how-far-apart-to-plant-avocado-trees/

Three avocado trees in one hole can work. I’ve done it and I’ve seen it done by others many times. Really the only key to its success is pruning the vigorous varieties so they don’t shade the slower one too much.

HI Greg,

Just ordered my second box of your delicious avocados. My wife thought the price was too high, but when she tasted the Pinkerton I got permission to order a second box 🙂 Thank you so very much for exposing us to new varieties.

Anyhow, I am wondering which avocado trees you have in your yard? I am up in Oakland, and last year I planted Fuerte and Little Cado, and still have Hass and Mexicola in the pot. Need to cut down some other trees to plant those.

Thanks again!

Hi Nikhil,

My pleasure! I have around 30 avocado trees in the ground in my yard, all of different ages and mostly different varieties. It’s changing every year, as I plant new ones to try and cut down others that don’t earn their keep.

Hi Greg,

Wow, 30 avocado trees. A true orchard. Would you mind sharing which haven’t earned their keep over the years?

Hi Nihil,

Saying I have 30 avocado trees makes my yard sound like it’s more of an orchard than it is. Most of these trees are very young and small.

A few that I’ve removed are Holiday and Sir-Prize. Both of these varieties make fruit that taste good, but it’s mainly their tree structures or growing habits that I didn’t like or weren’t conducive to my hot, inland climate. They’re not bad varieties. They can be good choices for certain situations, just not mine.

I’d like to offer my input about controlling rodents around avocado trees. I have an owl box designed for barn owls 12 feet off the ground on a post. I’ve seen half rat-bodies (tail end) under it and regurgitated owl pellets. I it know that the owls are eating rodents. My friend has one in an urban location near a park. Mine is on10 acres. Thanks for all the good info here.

Here is a link to more info about birds controlling rodents: https://www.wildfarmalliance.org/bird_training_lesson_4?utm_campaign=lesson_4_invite_general&utm_medium=email&utm_source=wildfarmalliance

Greg, I’m looking for some of those tree signs. Did you make them? Are you selling them as well?

Hi Ben,

My brother makes those signs and he used to sell them but no longer does, sorry.

I thought I planted a Pinkerton… So, I live in the San Francisco Bay Area. I planted two avocado trees a Pinkerton and a Jim Bacon. In the 3rd or 4th year (2020) my Pinkerton fruited. I started picking one at a time in April (2021) and waited 2 to 3 weeks for the fruit to ripen. Eventually, it seemed it wasn’t any good until June! Both trees flowered May/June and set fruit. I decided to wait for May/June 2022 before picking the first fruit. I picked one in late May and waited almost 2 weeks for it to ripen. The skin remained green, the flesh was good, but a little watery. So, I decided to wait until end of June to try again. This afternoon, a fruit fell and the skin was so dark it appears black. The rest are still green. I’m so confused. Do I wait 12 months? 18 months? And why does the skin look black? Maybe I don’t have a Pinkerton? What could I have? It set so much fruit this year (May/June 2022) that I’m so looking forward to all those home grown avocados… but I cannot seem to match up the harvest dates with anything I’ve read. I’m hoping you have some insight for me.

Thank you so much for all the great info on avocados. I made at least 5 attempts over the years to grow various varieties and I finally have success much do to reading your articles over the years.

Hi Monique,

It so happens that I picked the last Pinkerton from my tree on June 5 and it ripened and tasted great even though they can also taste great in February.

Pinkerton is a weird variety in that it has a long bloom season, at least it does in some locations. This means that an avocado that starts growing after setting at the beginning of the bloom season can be months advanced over an avocado that sets at the end — all on the same tree.

I’d guess that you probably do have a Pinkerton. You’re probably going to have to spend a few years getting to know your tree better, including how it behaves in your particular microclimate. This will be easier as you have more fruit to test in the coming years and don’t have to fear wasting its few fruit.

One clue I’d share is that the skin of Pinkertons get dull (lose their shine) at maturity. Maybe this will help you pick individual avocados from your next crop.

Hi Monique

I live in Concord and just planted a Pinkerton. What town do you live in and what type of planting area do you have. flat or sloped. I’m always interested in growth areas for Avocados in the Bay Area. Thanks, Tony

If you are in the bay area, there are a ton of microclimates. If you are out in the east bay, it gets a lot hotter and a lot colder than, say, the peninsula. And the peninsula/south bay gets a lot hotter and colder than the coast. Those factors and that we are farther north will definitely make your harvest times different, especially compared to the San Diego area.

Thanks for that help, Dan.

Anyone with a mature Pinkerton tree in the Bay Area care to share their general harvest times (and bloom times)?

Hi Greg,

Thanks a lot for your so great information about the Pinkerton. I just got a new Pinkerton avocado tree yesterday and was thinking of planting it on the grass lawn in my backyard. But I googled and was told it’s not good for planting on the lawn. My location is 9b. What do you think about that? And how tall the tree will get and how fast the tree grow?

Thank you again!

Amy

Hi Greg,

Thanks for all the info you post about avocados, its very helpful.

I picked up a 10# pot pinkerton and a 3# carmen hass. I’m in Santa Cruz area, in a microclimate thats a bit warmer than most of the greater SF bay area, but still colder than most SoCal. No frost though!

My question is which of these trees will get bigger? I want to make sure not to steal too much sun.

I also hear rumours that the Pinkerton can tolerate more shade than most avocados, do you know any others that do ok in less than 7 hours of summer sun?

Thanks!

You know how bad I want to grow this particular variety? I’ve never eaten one of these in my life. This for me is a must-try.

Hi Greg,

I just want to share my 20 years old Avocado tree from seed. The fruits are huge and taste is really good. Im not into avocado before but this I planted Pinkerton and Zutano from Home Depot. I have matured Fuerte that did not give more fruits and the other one is the 20 years old from seed. Im into grafting started this year and statrted grafting Hass from my neighbor to Fuerte and some from my old three. Can i call that avocvado three from seed into my name? its gonna be “Token Era” avocado.

Token Era avocado it is!

Hi Greg. After rereading many of your articles several times, I went out and bought 6 trees. A Gem, a Lamb, a Pinkerton, a Carmen and two Sharwils. I’m up north in a 9b micro climate in Humboldt County. I figure to plant them in groups of three 6 foot spacing intending to keep them between 8 and 10 tall maybe growing into each other. I have been going over (and over) which to group together. I figure to put a Sharwil in both groups as a possible pollinizer. I already have a Hass, a Wurz that have been in the ground for about 5 years, came through last years hard winter just fine, but no blooms. A Mexicola that is blooming now when there are no bees and a Zutano going through its second winter. A second idea is planting 3, and 2 together and 1 near the Zutano. Any ideas which might do better or worse together? Thanks and keep up the good work. Much appreciated.

Hi Larry,

There are so many options that it can be overwhelming, but I would say that the most important element of your design is to make sure that the Pinkerton is not too far from a B type (Sharwil or Zutano). Out of the varieties you have, Pinkerton has the greatest need of a pollenizer. The others do a better job of producing well without other varieties nearby.

Secondly, if they’re planted close together, they will be easier to manage in the long run if varieties with similar growth habits are next to each other. I would not put GEM or Pinkerton next to Zutano, as Zutano will quickly tower over them and you’ll have more pruning work. The others will get along better.

Thanks for the reply. I’ll go with your advice and put a Sharwill between the Carmen and the Pinkerton. And the Gem in front and a little higher than the Lamb and the Sharwil a little lower. It’s a good sunny spot in a slight rise.

I’ve been getting my trees from Four Winds with no problem. This second Sharwill came from another source and doesn’t look much like the Four Winds Sharwill. Very dark leaves, somewhat “tacoed.” The Four Winds Sharwil has lighter leaves and new leaves are a light rosy color and flat. If it looks to over power the Gem and Lamb, I’ll take it out and replace it with either a Gem, maybe a Gwen. My trees are begging to be out of the green house and I’m itchy to get going and the weather has been mild so i might start planting this week. I cover the mounds with thick black plastic in the winter to keep this rain rivers off and maybe add a degree or two to the mound.I’ll send a few pictures later in the process to show how avocados do (or don’t do) in the North Coast. Fingers crossed. Thank you for your Yard Posts, the pictures, sources – they’re inspiration to us just starting out.

Hi Larry,

Thanks! Your covering of the mounds with black plastic reminds me of an article: “On our awareness of climatic effects of avocado yields,” by Zamet. It seems that small increases of soil temperature in a setting like yours can make a significant difference.

Hi Greg, do you notice any differences in Pinkerton fruit shape dependent on where they are grown? I buy fruit labeled as Pinkerton from a Fallbrook fruit stand. Most of the Pinkertons do not have a long neck. Much like the 2nd picture in your article, they tend to have a pointy top, but not an elongated neck. The other picture in this article of Pinkertons hanging in a Poway tree also don’t have a stretched neck.

https://gregalder.com/yardposts/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Pinkerton-avocado.jpg

https://gregalder.com/yardposts/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Pinkerton-avocados-on-tree-Brad.jpg

Are long neck Pinkertons dependent on the growing area?

Yes, Rey. This definitely happens. In general, what I’ve seen in California is that the farther inland they’re grown, the longer the necks on Pinkerton avocados.

I don’t know why. It might be related to the later flowering and fruitset inland, as Pinkerton (and many other varieties) usually bloom later and set fruit later in inland locations compared to nearer the coast. Many other varieties do the same, and these same varieties have more elongated fruit inland also (Hass and Fuerte, e.g.).

I heard an avocado researcher in Israel say that they grow Pinkerton in inland, hot regions there because it handles those conditions well, but they spray the trees with uniconazole (a plant growth regulator chemical that is illegal in California) in order to prevent the long necks in the Pinkerton fruit. (See here.)

Hi Greg, in your experience with what you know about Pinkerton avocado. Have you ever heard or seen a Pinkerton have the skin turn black like a Hass and ripen in a few days?

Hi Ben,

No, but late-season Pinkertons certainly ripen faster than early-season Pinkertons, and the skin can darken significantly, especially at the bottom end. Right now, for example, I’m looking at the last Pinkerton I picked from my tree on June 8: it’s almost ripe and the skin has darkened somewhat but it’s definitely not uniformly purple-black like a Hass gets.