My first experience composting was when I dug a hole in the ground and filled it with food scraps, garden waste, pig manure, and peach tree trimmings. Each night when I went outside to relieve myself before going to bed, I found a wild dog harvesting from the compost pit. I lived in Africa at the time.

Composting was simple then. Composting was simple there.

I’ve since worked my way through many more complicated methods and styles, only to return to simple composting. I suspect that you might like to compost in a simple way too. Who has the time or energy to make anything more complicated than it needs to be?

What is composting?

Composting at its core is just letting little animals break down organic material — organic material being pieces of plants and animals. In addition to the microscopic creatures like bacteria and fungi, little animals that are still big enough to be seen, like pill bugs and earthworms, feed on organic material in a slow and simple compost pile. If given enough time, all of the little animals break materials down so much that it looks like dark brown forest soil: compost. (In the photo at the top, the blue bucket goes in, the black bucket comes out.)

But notice who is doing the work. Who makes compost? You don’t. Little animals do. Even in the fastest, most sophisticated and supervised composting process, it’s the little animals that do the real work. They do their work faster if we get very involved in creating optimum conditions for them, true. I’m talking moisture, temperature, size of materials, type of materials. That’s fun to do, in a high school science experiment kind of way, but that’s not the only way, and it’s certainly not the “right” way. And in the suburban backyards where most of us do our gardening and composting, “rapid” composting methods are not often practiced because they’re difficult to pull off in such a setting.

Simple ways to compost

There are lots of other simpler, slower ways to compost. They all entail far less effort and understanding of the biology involved. I’ll describe a handful of them, each of which I’ve done myself, and note the advantages and disadvantages. Surely, one can be adapted to your household and garden situation.

Pile in bin: Available for purchase are containers built for composting, like this black plastic bin.

What I like about composting in this is that all of the materials are hidden, and because it’s totally enclosed it retains moisture well, which is helpful in our dry Southern California climate. Moist compost breaks down more quickly.

At the same time, I’ve found that the materials in the middle of this bin can stay too wet. If composting materials are too wet, they start to stink and they don’t decompose quickly. To counteract this, when using a bin like this one, I put wet materials mostly on the outside and dry materials mostly in the center.

This bin has a door at the bottom. Materials at the bottom of a compost pile break down most quickly, so you can slide open the door and pull some compost out to use in your garden at any time without disrupting the rest of the pile inside. That’s convenient.

Pile in wire cage: A cheaper, do-it-yourself option is to contain your pile in something like this wire cage, which I built by fastening together two of my tomato cages. (My post, “The best way to support tomato plants”.)

Similarly, I’ve seen people use wood pallets to contain compost piles.

The downsides are that they don’t look as pretty and they dry out faster compared to a pile in an enclosed bin. Since we don’t get much rain in Southern California, it’s not helpful if your compost pile is so exposed to airflow and sunshine.

Just a pile: The cheapest method, though, is just a pile with no containment. My mom does this. It’s unsightly to some people. The pile also settles into a wide pyramid since there are no walls to keep it upright. The wider and flatter the shape, the less heat will be retained, which will slow the composting process.

The upside of a simple pile is that, besides being absolutely free, it is easy to access. You can dig into the middle at any moment to grab some of the good, decomposed stuff inside.

Just a pile, in a hole: Putting your pile into a hole, as I did with my first composting attempt in Africa, rectifies the problem of the pile spreading laterally even though it makes accessing the decomposed stuff in the middle more difficult. So that’s the tradeoff. I have skirted this tradeoff by building compost piles in holes besides fruit trees, where I never intend to access the compost; rather, I cover the pile with wood chips once it has filled the hole and then let it rot in place forever.

Back in 2013, for example, I filled a hole between these two avocado trees with compostable materials. The trees have grown up and rooted into the rich, black nutrients that remain.

Spread under trees: Can it get even simpler, easier? Why yes it can — if you neither dig a hole nor form a pile, but simply sprinkle organic material on the ground. In our yard, we have a Valencia orange tree that is 25 feet tall and pruned up into the shape of a giant umbrella. It functions as our outdoor living room. So, when we’re sitting under it and snacking we simply drop the mango seeds, pomegranate peels, and apricot pits right at our feet. I occasionally add wood chips to the ground too. It looks messy, I’ll admit, but what could be easier? And I’ve never fertilized the tree in any other way, while it produces oodles of juicy oranges every summer.

Chickens: In none of these simple composting methods does one have to wield a shovel or fork and turn the pile. Turning the pile makes compost faster. But chickens can be employed to do this work for free. This is actually how I do almost all of my composting these days. (My post, “Chickens: my garden’s little helpers”.)

I know chickens aren’t for everyone, but if you think that you don’t have enough space or don’t want a stinky coop in your yard, then you might like composting through laying hens as we do: Our pen is four feet wide, eight feet long, and two feet tall; and it is the only home our little flock of four hens has. They eat our table scraps and garden waste and whip it into the best compost I’ve ever seen. And there’s never any odor as long as you add enough plant material to offset their poop production.

Principles of composting

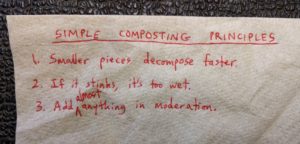

I can think of three things that even a simple composter like me needs to keep in mind. They can be written on a napkin:

A little elaboration:

1. Clip or mow some things before adding, if it’s not too much work. I often do this with cornstalks and old tomato vines.

2. Just add dry stuff like dead leaves or twigs, or open the bin to the air and sun.

3. I add a lot of things that many people say not to add, and I’ve never encountered any problems: meat, bones, oils, fats, eucalyptus, wood ash, plants that have bugs on them, plants that have diseases. I understand if that makes you nervous, but you might try it and see what happens. On the other hand, I don’t add some things: weeds that have seeds, and materials that are thorny. Weed seeds will not be killed in a simple, slow compost pile. Materials like raspberry canes and bougainvillea or rose prunings will still be there to bite you unless you leave the compost pile for a decade.

When is compost finished?

Organic materials will never stop breaking down and being eaten by the microbes, so in that sense the composting process is never finished. Use compost whenever it looks the way you want it to look. I use compost that is still chunky to spread as mulch under fruit trees, but I wait longer and also screen out big bits if I want to use the compost in containers for starting vegetable seeds.

Video

While I don’t know of an excellent video about simple composting — maybe because it would be too short to be worthwhile — I can heartily recommend watching this video showing Charles Dowding’s slightly complex composting method. He shows his piles in different stages, what he adds to them, and why they transform as they do. Charles Dowding is always worth listening to.

You might also like to read my posts:

I love this post. It has inspired me in a couple of ways! Can I get your advice and help on both a chicken coop and a compost pile?

Good to hear! Thanks. I’d love to help with those. If you’d like, you can write a couple questions here so others can glean from our discussion.

Let me also mention that I’ll be giving a presentation on keeping chickens, especially as garden helpers, at the Master Gardeners Spring Seminar in March here in San Diego County. I’ll write a post about that event with more information in a month or two.

Thank you. I was told to never put a compost pile under a fruit tree. You have solved that problem.

Do you have experience growing Comfrey? I picked up a “Bocking 14 Comfrey” plant to compost the leaves as its said to mine minerals and nutrients from even the poorest soil. The nursery said it won’t make seeds but the root system is pretty invasive. Before I plant it I wanted to make sure it’s safe and won’t take over my garden. Can I plant it relatively close, maybe 5 feet, from avocados/citrus trees or should I find a nether region of the yard to stick it into?

Hi Eric,

I’ve never planted comfrey, for some of the same reasons you mentioned. Sounds like it could become more work than what it’s worth. I’ve heard all of the magical claims about it, but I’ve never tried it out so I don’t know. If you do, please let me know how it really goes.

Hi Greg, I started composting back on the east coast by reading a monthly publication by Rodale Press, Organic Gardening. I learned a lot about gardening, soil and plant care. Over the years I’ve tried many different composting methods.

I now live in Mission Viejo CA and our soil most definately needs compost. We have clay which has it’s problems. As you have written in prior articles clay can be inproved by adding vast amounts of compost.

I tried the dig a whole method and while it works wonderful in our area we have racoons and possums that are always on the look out for my compost holes. If they kept there digging to just the hole it would be OK. Problem is they dig everwhere. And even when i fill the top of the whole with a 3″-6″ layer of dirt with their incredible noses they find it.

I also tried sheet composting under my avocado and citrus trees however using kitchen waste with this method is unsightly because of the visibility of banana peals, egg shells and other kitchen waste of similar size. This also attracts a lot of critter visitors.

With our covid 19 lockdown our town cancelled our April free compost give away which I was counting on taking advantage of.

So I came up with a means of creating more of my own compost, from yard trimmings (I have ficus trees, shrubs, and a slope I planted with enough rosemary to supply China with). I spread the kitchen waste on my rear lawn along with all trimmings. Some of these trimmings are leaves of course along with sticks up to 3/8″. I run my Toro 5HP lawn mower over all of this and I end up with a finely chopped mixture which breaks down faster. So far no critters, perhaps the rosemary strong scent is helping. It does a great job of retaining moisture as well as adding valuable nutrients to the soil because of the small size of everything going into it, it breaks down faster.

Previous to this I also tried building a compost bin out of concrete paver stones. I left slots between the stones to allow air in and combined kitchen and yard waste. The yard waste would bread down but the larger pieces of kitchen waste took forever. This method also was subject to waterlog with the monsoon rains we get once in a while.

So for now the spread, shread and spread seems to me the easiest way. I’m a real fan of your posts.

Thanks for that, Ron. I have also done a little investing lately so that I can finely chop up ingredients. I bought a small electric chipper-shredder on the advice of a friend. I had used a gas-powered chipper in the past that I didn’t like. So this winter and spring I have been feeding all of my tree prunings into this machine and making my own mulch and ingredients for compost piles, and it has been working great.

Hi Greg! Thank you for always providing such great information!

Would you mind sharing the make and model of the chipper shredder you bought? We have a small gas powered chipper and it’s so loud, gas fumey and heavy. I would love to replace it with something electric!

Hi Sharie,

Sure! It’s the Sun Joe model CJ603E.

Thank you!

As I browse your site I always find something interesting. Composting. I’ve had a worm bin for about 25 years. Certainly not the easiest method of composting, and somewhat limited on what is appropriate to throw in there (or so I’ve read). One suggestion I followed for several years was to put egg shells in there, to help battle the tendency for acidity. It didn’t seem to me that the egg shells ever broke down. Or at least not completely. I suppose my vision was short sited, wanting it done in a year or less.

I saw what looked like egg shells in the bucket at the top of the page. What’s your experience with egg shells breaking down time wise?

I’ve started tossing may avo shells, and other hopefully non-attractive food sources under my avo, orange and persimmon trees, thanks for the tips on this page!! Just hoping the neighborhood varmints (coyotes, possoms, racoons, rats, etc. ) don’t find these as food sources. Based on the lack of attention paid to my orange tree I’m guessing I’ll be ok.

Hi Matt,

I’ve been running most of my compost through the chickens for the last handful of years and the chickens eat the egg shells so I don’t end up seeing them in that finished compost. But when I do make piles near fruit trees that the chickens never touch, the egg shells definitely remain in bits for a long time. How long? I’ve never tracked it, unfortunately.

I’ve recently had some crows making a mess of any compost piles that aren’t covered. But there are definitely things that no varmints are interested in, at least in my yard, such as orange rinds.

Hi Matt & Greg!

I read a long time ago that while worms need the eggshells they can’t break them down when they’re whole so I blend them in my vitamix with some water and then give them to the worms.

Hi Greg

I’m getting so much from your posts, inspired to do more just by your example. My Haas and Fuerte have done nothing in 2 years. I blame the squirrels, but will look in your posts for better answers.

The article on Meyer was so good. Recently I went down a rabbit hole while looking into mirlitons ( chayotes) and it was fascinating, encompassing New Orleans culture, history, and plant explorers of the USDA. That’s how your posts are to me, covering many of my interests such as chickens, compost, avocados, citrus and reducing/ uncomplicating as much as possible. Ruth Stout was my original inspiration.

I look forward to learning more from you and your readers.

Thank you, Carmen. I enjoy watching old videos of Ruth Stout. I love her approach and her attitude.

Hi Greg, thanks for all the info, I’m inspired. I’m a new gardener and my issue is that I’ve been taking kitchen veggie waste, putting it in my food processor and then burying it around my yard under the mulch, a batch at a time. Is this a good thing to do to help my soil? Obviously, I thought it was. Seems like some places where I’ve done this tho, my plants didn’t do well. Wondering if the ground up veggies are taking needed nitrogen (or anything else) out of the soil as the wastes decompose? Or will this wonderfully help the soil’s fertility?

Hi Marsha,

I think you’re using an acceptable method there. I do something similar sometimes, and I know friends who do too — with one caveat. We do it near fruit trees, not in our vegetable gardens. I don’t know how well it would work near vegetables. Near fruit trees, however, I’ve never seen any problems and it does seem to enhance fertility as you’ll notice if you dig in that spot some months later that there are many roots growing into the decomposing waste.

thanks for the info, much appreciated

Hi Greg, like always your post are very informative.

We do a lot of boiled eggs.

The water that eggs are boiled is dumped on to the compost pile or right onto potted plants, good source of calcium for plants. The egg shell are placed in a bucket in the garage to dry out. After a period of time I take the dried egg shells, place them in a plastic bag and run a rolling pin over to break them down, a little work but doesn’t take long before they are composted.

Have fun rolling!

Pertinent and helpful, as always. Two questions: How old is your Valencia orange tree? What about big white larvae-looking things in my compost? The compost is excellent.

Smells good. But the big white worm-things I pull out and feed to the crows. What are they? Friend or foe?

Hi Alex,

Thank you. Don’t know how old the Valencia is, as I inherited it with the property. But I’d guess it’s 30-40 years old.

Those fat grubs in the compost are a little friend and a little foe. They are the larvae of some kind of beetle, like a green fruit beetle or June beetle/bug. In your compost they’re definitely a friend since they’re helping the decomposition. But then after they metamorphose into beetles they can be a problem; they eat your ripe peaches or avocado leaves, for example.

Here’s a good article with more on the white grubs: https://ag.arizona.edu/yavapai/anr/hort/byg/archive/whitegrubs.html