You want your vegetables and fruit trees to grow well and provide you with good food, so you seek advice about how to create the best soil conditions for your plants.

You encounter this recommendation in Sunset’s The Edible Garden book about how to grow broccoli: “Feed with a high-nitrogen complete fertilizer before heads start to form.”

And then you try to figure out how to apply such a recommendation: Feed how much — a tablespoon, a cup, a bucketful? And what kind of fertilizer is considered “high-nitrogen?” What makes a fertilizer “complete?” And then you think a little further and wonder, what if the head of broccoli starts to form before I notice — should I still feed, should I feed more or less?

Maybe you also come across instructions about preparing your soil before planting, such as the tens of pages dedicated to the topic in the book How to Grow More Vegetables by John Jeavons. There are multiple diagrams, side notes, illustrations, suggested tools, and within the text you find the ironic phrase, “Do not strain yourself . . .”

Alas, after crunching your brain figuring out how to apply the recommended fertilizer and getting a workout from all that “double digging,” you’re convinced that fertile soil requires a degree in chemistry and an Olympian’s energy.

You can go that route and you’re likely to get good results. But there is another way. In fact, achieving and maintaining fertile soil can be child’s play.

I learned to grow vegetables and fruit trees while living on the outskirts of a rural village in Africa, where no chemical fertilizers were available and where everyone’s days were filled with chores like fetching water from the spring and hand-washing clothes. Food was grown in the simplest and most expedient way. When I returned to the U.S. and took training classes to become a Master Gardener I learned a lot, but I also very often remember listening to a PhD’s lecture and thinking, “It doesn’t have to be that complicated.”

Well, who am I and how do I know? I’m just a guy who’s been doing it a simpler way for more than a decade now, and I eat the proof that my soil is fertile every day.

For my vegetable beds, I add about two inches of compost each year. I usually add about an inch in late winter before planting tomatoes and corn and peppers, and then I add about an inch again in late summer before I plant my cauliflower and cabbage and onions. There’s nothing special about those times; it’s just when I usually do it.

I merely spread the compost on top of the soil. I don’t dig it in. There’s no need. It gets incorporated into the soil naturally, eventually.

(See my post, “Don’t dig in your garden.”)

Sometimes I use compost that I’ve made in my yard, which includes some of our chickens’ poop, and sometimes I use compost from the Miramar Greenery in San Diego, which is what my sons are helping me load in the photo at the top. I’ve noticed over the years that plants grow better with my compost compared to Miramar’s, but unfortunately I’ve not yet been able to produce enough of my own.

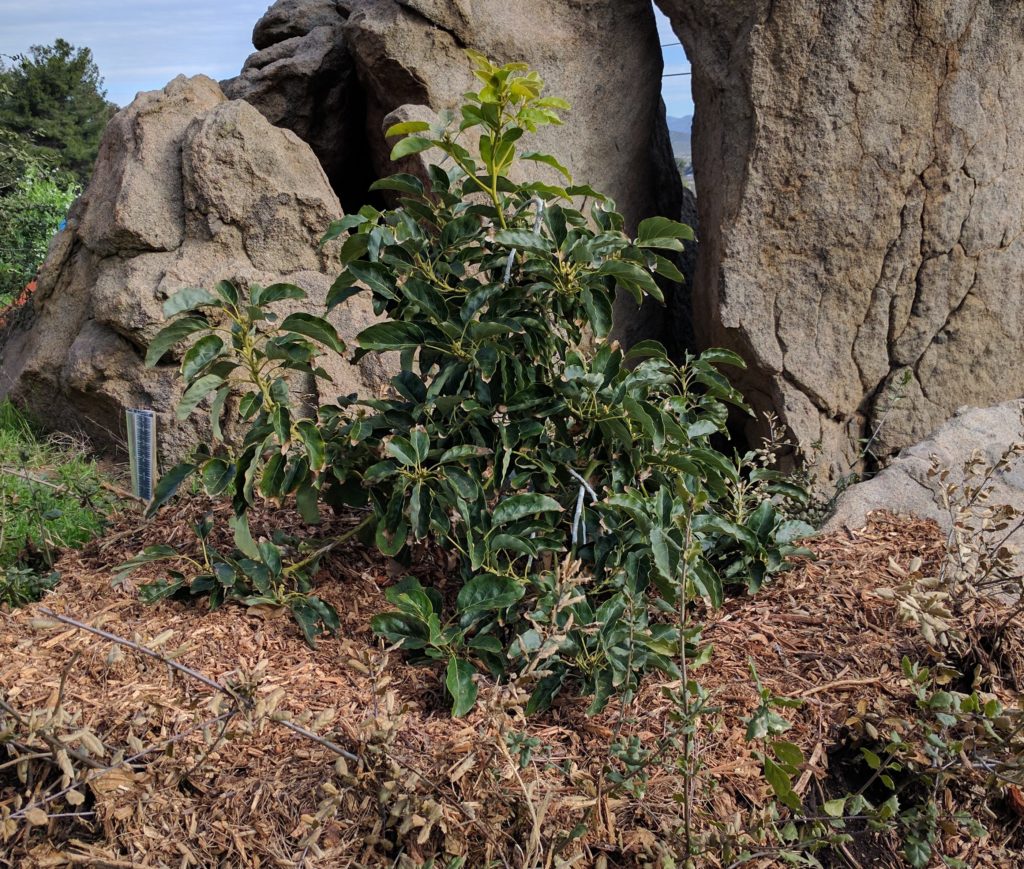

For my fruit trees, I sometimes add a little compost too, but only if I have more than my vegetable beds need. Mostly for the fruit trees I just keep a thick layer of wood chips as a mulch under them. Over time, the wood chips break down and are incorporated into the soil just as the compost is in the vegetable beds, but I tend to only replenish the wood-chip mulch once a year. I like to do it now, in late winter, so the rains soak the mulch for free, but I do it at other times if good wood chips become available then. I aim for a new, replenished depth of about five inches each time. There’s nothing magical about this depth, but a thinner layer will vanish into the soil more quickly and a thicker layer gets awkwardly close to low-hanging branches.

Sometimes I also get wood-chip mulch from Miramar Greenery, but often I get wood chips from a tree trimming service who is working in the neighborhood. It means they don’t have to pay to dump their load elsewhere, so it benefits both of us. I was lucky enough to get a load dumped last week, so I’ve been replenishing the mulch under my trees over the past few days.

(See my posts about using wood chips as mulch under vegetables and fruit trees. And my post about where to get wood chips.)

Is compost really enough for fertile soil in vegetable beds? As I said above, I eat the proof every day, but so do others. My friend Erik, for example, has added only compost on his vegetable garden for a number of years and his plants do as well or better than mine. And the British market gardener Charles Dowding certainly grows a heck of a lot of beautiful vegetables using only compost.

And are wood chips really enough for fertile soil under fruit trees? Again, the proof is in the pudding. I couldn’t imagine getting any more fruit out of my Valencia orange tree:

But it’s not just me. The other day I visited a friend who has an extensive orchard in her backyard. This woman is a certified arborist and a certified Master Gardener, she grows an astonishing variety of fruit trees — from Jan Boyce avocados to Honeyhart cherimoyas to SpiceZee nectaplums — and she puts nothing more than a thick layer of wood chips under them.

(Paul Gautschi follows a similar routine up in Washington, and Ruth Stout was doing something similar a hundred years ago.)

How is it that compost and wood chips do all of this work — creating and maintaining soil fertility without any additions of specially formulated fertilizers or constant tillage to loosen the soil? That is a question whose answer is book length. But here is a list of some specific effects that compost has on the soil, along with an attached bibliography for deeper reading.

And here is an excellent publication by Linda Chalker-Scott of Washington State University on the documented effects of using wood-chip mulch, which you’ll find are nearly the same as compost.

However it works, and however much we do or don’t understand it, the evidence is there. You can give your mind and your back some rest, and perhaps give your kids some fun with a shovel every now and then. For a simpler path toward soil fertility exists.

A few related posts:

I enjoyed reading your posts. I’ve set up my chicken run with a big compost pile that feeds my chickens almost 100% of their food intake. They eat the food scraps, all my yard/garden waste, and all the biological life that grows in the compost . They are extremely happy healthy birds. It allows me to have 30+ chickens for relatively little cost. I have to give away compost because I can’t use it all. Chickens are really the key to great soil. As Paul Gautschi says, “My chickens are my soil generators, the eggs are just a nice by product.”

If you’re running short on compost you might consider making a permanent compost pile/chicken run and adding more chickens to up the production.

Thanks for sharing this, Travis. Greatly appreciated.

Hi Greg ~ I’m in Santa Barbara. You helped me with my 1-1/2 year old Blenheim Apricot, espalied Anna’s Apple, and Santa Rosa plum some months back. They are now 2 yrs old. The Anna’s had 2 apples this year and the plum and apricot had no fruit. They are planted 18″ off a neighbor’s garage wall and get 5-6 hours of good sun a day. I use wood chips and a drip system. I did feed them in May. During this hot summer we watered twice a week, Mon & Thurs for an hour. I think they get about 1-1/2 gallons each time. They are semi-dwarf. All that said, I gave the plum and apricot their summer pruning yesterday. (No pruning of the apple) I Googled and read many articles and am so hopeful I’ve done right by them. Do you have specific articles on pruning these trees? Also, am I correct to back off watering now to once a week? Any and all guidance on the care of our little orchard is so very much appreciated! Just love all the wisdom and experience you share each week! Have shared your emails with several gardening friends.

Hi Judy,

Good to hear the updates on your trees. I’m pretty sure watering once a week here in September would be fine. I’ve backed off to every two weeks or so. But be sure to give them enough water each time. Even in mild Santa Barbara, the three gallons each week you were giving them may not have been sufficient for good fruit production unless they are still very small. I would consider bumping it up to more like a two-hour run each time, or more. But since I’m not looking at the trees and feeling the soil, don’t take this suggestion too seriously.

With regard to pruning, my only relevant articles so far are “My best advice on pruning deciduous fruit trees: Keep them small” and “Don’t cut off the fruiting wood: Pruning lesson number one.”

Links: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/my-best-advice-on-pruning-deciduous-fruit-trees-keep-them-small/

https://gregalder.com/yardposts/dont-cut-off-the-fruiting-wood-pruning-lesson-number-one/

More to come!

Are there specific types of trees that one should not use as wood mulch?

I recall being told that my eucalyptus was not good for mulch, when our old tree was taken down at my former property.

One local landscaper was offering pine mulch, but had a lot of pine needles mixed in. He didn’t recommend it for gardening mulch.

I plan on getting free wood chips from that landscaper, but don’t know what trees are best, and which ones to avoid. We have a muddy mess after letting the grass die at this new-to-us house in Santee.

Hi Mo,

I’ve yet to meet a type of tree whose chipped wood isn’t good as mulch. I do have my favorites, but I’ll use almost anything available. I only don’t like using a lot of palm because it’s hard to handle and the thorns can be inconvenient to walk on.

I wrote a bit about this in my post, “Using wood chips as mulch for fruit trees.”

As for eucalyptus specifically, it’s fine. I’ve used lots of it, as have many others.

Pine? I love chipped pine. I’ve used lots of it too.

Probably my favorite is oak because the mix of wood and leaves make an airy, bulky mulch that is also easy to distribute and spread.

Good luck with that muddy mess!

Also, it took a while for me to realize that the red painted decorative mulch my dad gets by the bag at the big box home improvement stores DO NOT have the same benefits you listed.

Their garden had not produced as much, and certain years it doesn’t give ANY fruit. They resorted to using synthetic fertilizers, without much success. Proof that you can’t rush nature and it’s natural process of building soil, not dirt.

Hi Greg,

I love your blog. I’m a newbie trying out your gardening style and have a couple questions:

1) You wrote that you use about 5-7 inches of wood chip mulch for fruit trees. What about in your garden pathways? From pictures, the depth seems to be a lot less. I recently added ~3 inches to my pathways and after stepping all over them, I already feel like they’re going to disappear quickly.

2) Does the no-fertilizer approach still work with young fruit trees that are just getting established? Just plop in the ground and cover with mulch too?

Thank you!

Hi Arden,

I really like your questions. At first, the wood chips on my garden paths broke down and needed to be replenished faster than now. So however much you add during the first couple applications, you’ll find that over the years you have to add much less, or much less often. I can see that eventually I may never add wood chips to my paths again.

If you just plop a new fruit tree in the ground and cover the surrounding soil with wood chips and/or compost, the tree will grow fine — almost certainly. If you also add some fertilizer, in appropriate ways, the tree will probably grow faster in its first couple years.

I say these things after having grown so many fruit trees of different types in different yards with different soils using the mulch-only approach while also comparing these trees to those in yards’ of friends who fertilize. So the question of whether to fertilize a young fruit tree comes down to mostly how patient you are and not to how healthy you want the tree to be.

My fruit trees are, on the whole, healthy and productive, but they have usually grown more slowly and sometimes started producing later than comparable young fertilized trees — definitely not always, but sometimes. Because of this, I have started adding some chicken manure/compost to the soil surface under my young avocado trees so that they are slightly more vigorous in their first year. Usually, I notice an increased rate of growth. My yard gets pretty cold in the winter, and I want new avocado trees to have enough foliage to take some frost damage in their first winter if necessary. I don’t fertilize any other fruit trees while young because they have no such vulnerability.

Gotcha. Thanks for your thorough reply, Greg!

Hi Greg,

Wish I’d found your website sooner, as you have such wonderful information, and I like that you want to simplify the process. I have access to horse manure from neighbors, and wonder if I just mix this with soil when planting, or add to my compost bin to sit for a few months? I’d appreciate your thoughts.

Thanks, Laurie in San Juan Capistrano

Hi Laurie,

Thank you. I’ve added fresh horse manure to the surface of vegetable beds, and also let piles sit for almost a year before using it, and also added it to compost piles. I haven’t noticed anything strange in any of these situations. Whenever I’ve added the fresh stuff to beds, I just haven’t put it under plants like lettuce that I’m going to eat fresh soon.

You’ll read that manure should be allowed to age so the salts leach. I’ve never followed this advice consistently and I haven’t seen any problems except that I once did an experiment where I sowed a variety of vegetable seeds directly into fresh horse manure and I saw that some of the seeds grew poorly compared to the seeds I’d sown into compost.

You might want to test a small amount of manure from your neighbor first just to make sure it doesn’t have a lot of seeds. I once got a load from someone that grew oats all over wherever I spread it.

Thanks for your reply Greg. Because you like simple, I figured that you’d try the manure using different methods, and you did! Thank you!

You commented on using compost from Miramar Greenery, is there a place that county residents can get compost?

Hi Marilyn,

Anyone can get compost from Miramar, not just San Diego city residents. It’s just that you have to pay a small fee. Also, there is a facility in Oceanside that makes excellent compost called El Corazon, run by Agri Service. Similarly, its compost is free to Oceanside residents, but anyone can pay for some.

I’m starting a couple of new beds for winter. I have some of my compost and some compost that I’ve obtained from a yard. I intend to use both on these new beds.

A neighbor who has chickens has agreed to give me their poop. Would you apply this directly to these new beds as an additional amendment or add it to my compost pile to break down further and use sometime in the future?

Hi David,

I’ve used fresh chicken manure added to the surface of my vegetable beds with good results. I’ve done this to numerous beds this spring and summer, in fact.

I’ve also added it to compost to further break down, at which point I can use the compost to start seeds in even without any problems. I also spread this “chicken compost” on the surface of vegetable beds.

What I haven’t tried is incorporating fresh chicken manure into the garden soil where I’ll immediately after put in plants. My guess is that doing that might run the risk of burning some plant roots. I have tried exactly this with fresh horse manure and seen some plant damage (yellow leaves, stunted growth).

So in short, I’d add it to the surface or add it to the compost for later use.

Thank you!

Hello. I use sugarcane leaves as mulch on my vegetable garden (some people have access to hay, i have access to sugarcane! lol). I also use wood around the fruit trees. When adding new compost on top, do you have to clear out the mulch, or do you put it right on top of it and let the mulch decompose under it? Thank you!

Hi Li,

I take the easy way and just add compost on top of the mulch. After some watering, the compost mostly works its way into the spaces in the mulch and gets under it over time.

Mountain Meadow Mushrooms in Escondido, CA offers free mushroom compost. Do you have any experience with it?

Hi Dave,

Yes, I have used the compost from Mountain Meadows. My favorite aspect of it is the texture: so airy and friable. I have found that it is a nice addition to the surface of my vegetable beds and under fruit trees, but it is not the best to start vegetable seeds in. See my post trying to start vegetable seeds in it here: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/experiment-comparing-composts-for-vegetable-seed-starting/