Before I had my own avocado trees, I picked fruit from the trees of others (and usually I asked first). I had learned the locations of trees of different varieties and in which season each tasted good so that I could find avocados to eat all year.

Later, I asked avocado farmers why we consumers could only get poor-quality Hass avocados from Chile or Mexico in stores in Southern California during the winter. I was eating delicious Bacon and Fuerte avocados from local trees at this same time. Their answers related to marketing and handling efficiencies and sounded convoluted and disingenuous.

The point now is, before I started planting my own avocado trees I knew that it was possible to get a year-round harvest. Local avocado farmers simply weren’t giving it to us. Since then I have discovered the challenges involved in actually achieving this year-round harvest in a single yard. Choosing the right varieties is only one of the challenges. And I hope that by writing this post I can help you overcome those challenges and live the dream of being able to pick excellent avocados from trees in your own yard every day of the year.

Others’ variety recommendations

Choosing the right varieties is where the quest for year-round avocados must begin. Luckily, California avocado growers and researchers have considered this topic for a hundred years, and the varietal recommendations of some are still worth mentioning today.

Frank Koch wrote on page 50 of his Avocado Grower’s Handbook, published in 1983, that a mix of Hass, Reed, and Pinkerton would permit harvest year-round. Pinkerton was a new variety in 1983.

Five years later, Gray Martin and Bob Bergh of U.C. Riverside, also suggested Hass, Reed, and Pinkerton, but they added the recently released Gwen variety as an alternative to the Hass.

The seasons of these varieties are roughly winter into spring for Pinkerton; spring into summer for Hass and Gwen, and summer into fall for Reed.

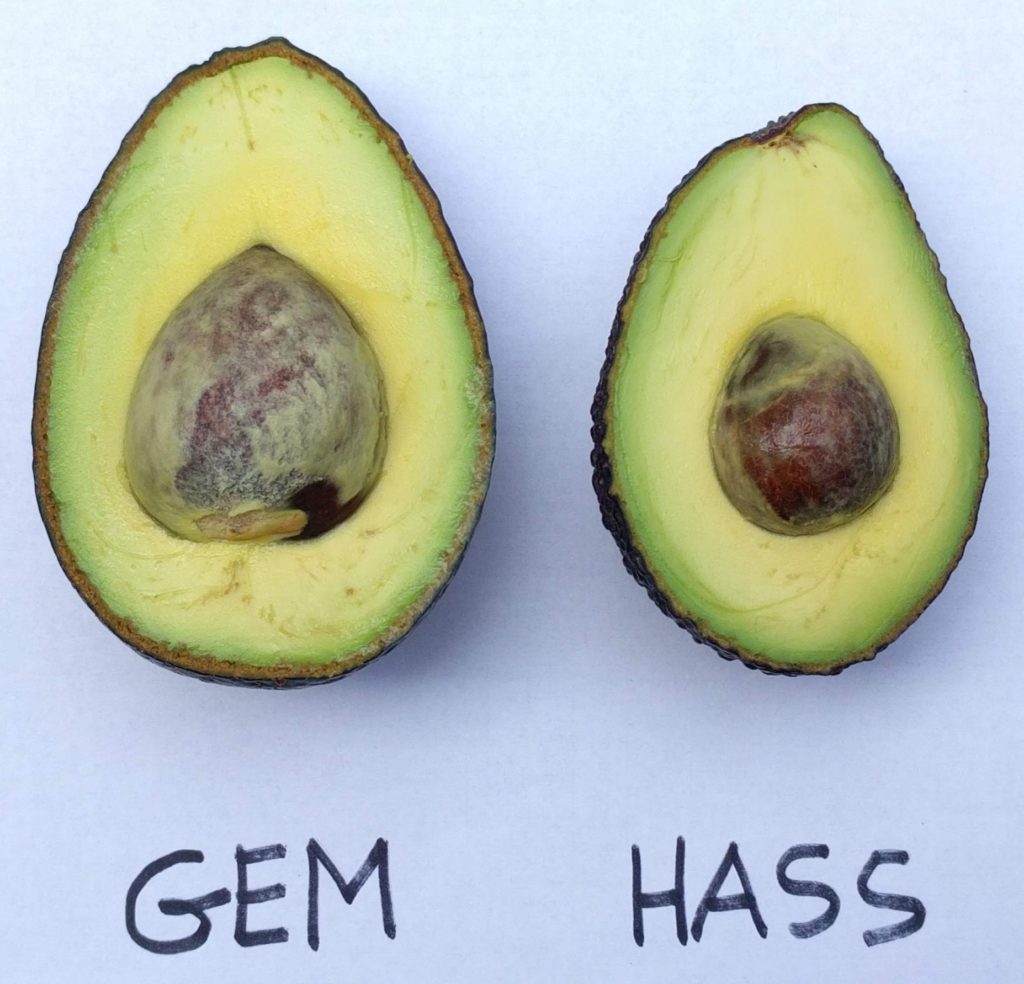

Gwen came from U.C. Riverside’s avocado breeding program, and over the past three decades a couple more worthy varieties have been developed, patented, and released. Mary Lu Arpaia, current director of the avocado breeding program, suggested in a talk on varieties in 2018 that growers consider GEM as an alternative to Hass (and Gwen) for the spring into summer window. For summer into fall, Arpaia suggested trying Reed or Lamb. GEM and Lamb are both products of U.C. Riverside’s avocado breeding program.

But what about for the late fall and winter? “We don’t really have anything for November-December,” Arpaia said. “Fuerte is good in December and January, if you want to take a gamble.”

The Fall Gap

As I have written about before, there is often a window of time that occurs as early as September or as late as December in most of Southern California, depending on the weather, where good avocados are in short supply. This gap, which I have come to think of as The Fall Gap, comes after the late varieties like Reed and Lamb are mostly finished but before the early varieties like Fuerte (and then Pinkerton) are up to par.

It’s not that there are no avocado varieties that fill this gap. Mexicola, Mexicola Grande, and Stewart are varieties which mature around this time and whose taste I enjoy. The problem is that they are not all-around as good as the varieties recommended above, in my opinion. In short, Mexicola is thin-skinned and very small, and Mexicola Grande and Stewart are also thin-skinned, have a short harvest season, and are occasionally stringy. The thin skin of these varieties makes the fruit prone to cracking and to chewing by animals. They are not bad varieties, that’s for sure; I just don’t think they’re on the same level as the others.

Best varieties for each season

So here is a list of the varieties that have been recommended above for each season, and with which I agree:

Winter — Fuerte, Pinkerton

Spring — Hass, GEM, Gwen

Summer — Reed, Lamb

Fall? — Mexicola? Mexicola Grande? Stewart?

I’ve listed the varieties in the order in which they mature. For example, Fuerte is mature before Pinkerton; Fuerte at the beginning of winter, and Pinkerton toward the end of winter.

(Here are my profiles of the Pinkerton, Fuerte, Hass, GEM, Reed and Lamb avocado trees.)

(Here are my video profiles of the Mexicola, Mexicola Grande, and Stewart varieties.)

Other varieties for each season

Still, we know that there are many other good varieties of avocados beyond those listed above, such as:

Winter — Bacon, Sir-Prize

Spring — Sharwil, Jan Boyce, Edranol

Summer — Nabal

These varieties are also listed in order of maturity.

The list could go on much longer, but I’ll leave it at that because these varieties are ones that I have enough personal experience with to say that they’re worth growing even though they wouldn’t be my first choices in their respective seasons.

A or B flower type?

The characteristics that I most desire in an avocado variety growing in my yard include eating quality of the fruit, productivity of the tree, and the length of the harvest season. All of the varieties in the “best” list taste excellent, have a long harvest season, and are highly productive — with one exception: Fuerte.

Remember what Mary Lu Arpaia said? “Fuerte is good in December and January, if you want to take a gamble.” The main gamble in Fuerte is its unpredictable fruitfulness. In part, this is related to its being a B-flower type. Avocado varieties are of two flower types — A or B — and it has been observed in California since almost the beginning that A-type varieties fruit more reliably overall. (See more on this from a paper by Peter A. Peterson.)

Jan Boyce is an A-type avocado variety, but Sir-Prize, Bacon, Sharwil, and Nabal are Bs. These Bs can produce well; I’ve seen loaded trees of all of these varieties.

However, because of the behavior of B-type varieties, their fruitset is more influenced by the weather and whether they’ll produce well in your yard is less predictable. In my yard, as one example, A types outproduce B types on average. One probably exists, but I’ve never seen a yard with multiple varieties of avocados where the story is different. So I’d choose an A type over a B type, all other things being equal.

I wrote a post a few years ago titled, “What’s the best kind of avocado to grow?” There I chose, in order, Hass, Reed, and Fuerte. But I’m here tempted to prefer Pinkerton over Fuerte for the winter window solely based on productivity. Fuerte tastes better, to me, but Pinkerton produces more. Such a trade-off! I’ll leave the choice up to you. (And I’ll keep both trees in my own yard, if that’s okay.)

Are three or four trees enough: alternate bearing?

So can you choose one variety per season and expect to get a year-round harvest? Realistically, probably not, not in sufficient quantity year in and year out. Individual avocado trees have more or less fruit each year, and sometimes the fluctuation is so extreme that a tree will be barren for a year.

Therefore, if you really want to ensure that there are great avocados to be picked from your yard all year long, every year, you ought to have two trees for each season, and ideally the two trees would be different varieties. Most likely, even if one is having an “off” year, the other will have some fruit on it.

I’ve seen this work out in my own yard. For the summer harvest, I have both Reed and Lamb. In the summer of 2018, the Lamb had an off year, but the Reed held a good crop. Then they reversed this past summer of 2019, and the Reed had an off year while the Lamb had plenty of fruit.

Two varieties for each season would make for six trees total if you weren’t adding fall varieties like Mexicola and Stewart. My personal choice of six, as my experience stands now, would be:

Winter — Fuerte, Pinkerton

Spring — Hass, Gwen

Summer — Reed, Lamb

Unless I had lots of land, I wouldn’t bother with Mexicola, Mexicola Grande, or Stewart for fall.

Mature trees have longest harvest seasons

Once an avocado tree of any variety reaches a certain size, where it is capable of carrying at least one hundred avocados (that might be a tree that is roughly 12-feet tall), the harvest season becomes longer than in prior years. It is because there are more flowers on the tree each spring, and the bloom season lasts longer, and the avocados are of slightly different ages, and there are so many avocados that it takes you longer to eat through them. All of a sudden, your Lamb still has avocados that taste good deep into fall, even winter, and your Fuerte already has some fruit that tastes good in December. Thus, The Fall Gap becomes a mere crack, even imperceptible. It’s not as big a void as it was when your trees were young.

This is not to mention the habit of “off bloom” that is common in certain varieties in certain locations, such as with Carmen. When avocado trees behave in this way, the harvest season becomes even more spread out for a single tree.

And varieties such as Pinkerton and Fuerte frequently have fits of early bloom, which means they might have a few fruit that mature far earlier than their main crop. For example, here is early bloom that I noticed on a Fuerte tree in San Clemente just yesterday, October 3:

Girdling

There are other methods of managing the natural alternate bearing of avocado trees besides just planting multiple varieties for each season. Some commercial growers routinely girdle their trees in order to manipulate flowering. Here is a link to a video of a commercial grower in Ventura County who girdles his trees in order to harness and manipulate their tendency to alternate bear. Through girdling (cutting into the bark), he stimulates half of each tree to flower and fruit heavily while encouraging the other half to be barren so that each year each tree has half of a fruit load. Watch this video of Paul Nurre on his girdling techniques.

Only space for two varieties?

If my yard could only fit two avocado trees — and remember that avocado trees don’t have to reach 30-feet tall — I would choose a Hass and a Reed, which wouldn’t quite cover the year but would get close.

Come to think of it, before I had my own avocado trees I used to pick from a yard that wasn’t big but had a beautiful pair of trees, a Hass and a Reed. There were excellent avocados ready to pick from those trees most months of the year. And then the house sold and the new owners cut down the trees and poured a slab so they could park their RV in the backyard. Is my schadenfreude wrong, as I imagine them complaining that the avocados they buy in the store so often have poor taste and rotten spots inside?

More about avocado varieties

Hungry for more information about more avocado varieties? Check out these resources:

Here is a list with descriptions of commercial varieties from Gary Bender’s Avocado Production in California (see page 30).

Here is a list of avocado varieties with descriptions and photos from U.C. Riverside.

Thanks to generous gardeners like you, my Yard Posts are ad-free. Learn how you can support HERE

You might also like to read my posts:

I so look forward to your posts, always informative. I have 3 Avocado plants, 2 Haas which are both about 6 feet tall and wide. I actually had a shade canopy built for them to protect the plants from the afternoon sun. I also have a 5 foot, Pinkerton. Trying to be patient and waiting for them to produce. I live by the coast in Pacific Palisades and grow some Peaches, Plums and lots of Apples and Guava and some Citrus. I think I am happiest when my hands are in the dirt! Thank you for your posts.

Hi Anupama,

Hass and Pinkerton are great choices for your area, being close to the beach. Every Hass and Pinkerton I’ve seen close to the beach that is healthy is very productive. At five or six feet, you should expect some flowers and maybe a few avocados setting this spring.

There’s a variety called Lil’ Cado. Any experience with this one or growing an avocado tree in a container? I’m in CA near Disneyland typical small suburban yard, starting to plan out my container Victory Garden.

Hi Giselle,

I don’t grow Lil’ Cado, which is also known as Wurtz, but I have seen some of those trees in other yards. I talked a bit about Wurtz and have a photo of one in this post: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/can-you-grow-an-avocado-tree-in-a-small-yard-space/

Hello Greg,

Wish you lived up here in Northern Cal. I am part of the rare fruit growers really enjoy your blog. One of the members (Marta ) has a blog similar to yours. I have also talked to Fred over at Epicenter nursery once on Avocados for Northern Cal. Here its more of what will grow than what tastes good ! people who love to eat Avocados will try to grow them anywhere its seems from going on line. The situation here is we have so many micro climes and even depending on where you plant.

I feel sorry for all the Hass and Bacon avocado trees sent up here by Monrovia and 4 winds growers to be sacrificed by homeowners at HD.

Finally after 3 yrs of trying I have some grafts taking of trees from peoples yards that have survived up here 40 to 60 yrs. I took a trip last year all the way up to Chico to get Duke cuttings but nothing I grafted last yr. survived. So far my Creekside and N. Fitch seem to be taking. One harvests approx. Late Dec. to end of Feb. and the other seems to be early summer ( June to July ) You have to know up here we get several days a year in the mid 20’s and about once every 10 yrs we get down to the upper teens. So any trees in peoples yards having lived that long are survivors.

Charles

Hi Charles,

Thank you for writing. I’m technically a member of California Rare Fruit Growers too, but my current schedule makes it difficult to get to meetings. I did make it to the Festival of Fruit last summer though.

I ran into Marta’s blog for the first time a few weeks ago. It is excellent. Some of her avocado information is so helpful to me in understanding the climatic differences that you mentioned between us in Southern California and you guys up there. In case anyone reading this wants to check it out: https://fruitsandgardening.blogspot.com/

I also appreciate all of the information that I’ve read on the Epicenter website: http://www.epicenteravocados.com/

What Fred and Ellen are doing is a blessing for everyone interested in growing avocados, not only those who live near the Central Coast. For example, I’ve found lots of commonalities with their experiences with B-type varieties. They wrote about this here: http://www.epicenteravocados.com/blog/

Every time I go up north I scout and photo avocado trees, but it’s been a few years since I’ve been to certain areas and I’m really eager to take a dedicated avocado trip up there to visit specific trees like the old survivors you mentioned. I hope I can find the time to do that someday soon.

Thanks again for writing, and I appreciate the contributions from your perspective up there.

I have been growing Fuerte n Bacon for many years in Modesto CA. Last year about 800 Avocados harvest. Protected first 2 years from frost n north wind. Mexicola Grande easiest to grow here . Have it now n Wurtz, Lamb Hass . Cloth over little ones for night time . Uncover daytime.

Hi I live in yuma az and I’m triying to grow two avocado tree one it’s a zutano and the other one is a mexicola any suggestion both of them are about 3 feet and they been on the ground for about 6 months

I am looking for a place to buy Puebla Avocado trees that may be shipped?

Hi Ginger,

Subtropica Nursery in Fallbrook is the only nursery I’m aware of that makes Puebla trees. They only ship large orders, not single trees.

https://www.subtropicanurseries.com/

Love this post! I started my collection with your recommendation of hass, fuerte and reed with the goal of getting a year round harvest. Since that time, I have added a lamb, sirprize, jan boyce, sharwill, pinkerton, nabal, and mexicola. I’m banking on that mexicola to get us through the fall, but if it doesn’t pan out that way, your insights here are very comforting.

Thanks, Keith! Someday you are going to be drowning in guacamole!

So much good info here!

Have you ever experimented with spraying honey water on the avocado blossoms to encourage bee activity? I recently heard about that idea and was going to try it next spring when my fuerte blooms since I had zero fruitset this year (and lost my entire crop last year in the July heatwave). See this video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-U8brEWeLXg&list=PLYE2HqZGtiULh7aPgUZ0xUkix9JkgeGuy&index=4&t=29s

and beginning at minute 19:00 in this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rX9pwyFb1rU&list=PLYE2HqZGtiULh7aPgUZ0xUkix9JkgeGuy&index=5&t=42s.

Since you have so many avocado trees in your yard it might be an interesting experiment to spray one and use another as a control in order to try to debunk or validate the use of honey water.

Hi Heath,

I toyed with honey water on my Fuerte flowers last spring and saw nothing promising. First, no bees or anyone else noticed the areas I sprayed. So I increased the honey portion. That time it drew a ton of Argentine ants but no bees, maybe because of all the ants.

I don’t plan to try it again, but if you do please tell me how it goes. Maybe I just didn’t do things right.

Hi ^_^

Just FYI

I tried the honey water spring 2019 on my 10 ft Hass. I have close to 300 fruits on the tree now. I had 2 different blossoms, so I still have 2 crops on my tree now.

There were mix of all kinds of flying insects that helped pollinate.

Hi Greg, I live in Kodaikanal, India, how can I preserve the avocados to last me the whole year. I have farm with quite a few avacado tress…. any help is much appreciated.

Hi Lucial,

The only way I’ve tried preserving avocados is through freezing. But after defrosting, the pulp doesn’t have great texture. It’s better than nothing, but barely.

I’ve successfully frozen ripe avocados whole. The less you do to them the better. Defrost a day or so before you want to eat them.

Your two-tree recommendation of Hass and Reed is interesting!

I’m wondering what you think of a combination of Lamb/Hass and SirPrize for a two-Avocado-tree backyard. Advantages I see are:

1. Having an A type and a B type in the same yard should improve both trees, right?

2. From the information out there, it seems like Lamb/Hass and SirPrize will need less pruning than Hass and Reed in a backyard setting.

Lamb/Hass+SirPrize seem to cover 10 months out of the year, almost as good as Hass+Reed’s 11 months according to https://www.ocfruit.com/files/Avocados.htm

Hi Andrew,

Lamb and Sirprize would make a nice pair. The harvest seasons are separated well. And A/B combinations are always helpful.

A/B combinations can be overrated, however. Sometimes the B does a good job aiding the pollination of the A but doesn’t set much fruit itself. I had a Sirprize growing beside my Hass for five years. My Hass was very productive throughout, but the Sirprize was so unproductive that I cut it down. (This is not to say that Sirprize is unproductive everywhere, in general.)

In contrast, I planted an A/A pair of Lamb and Reed. Both of them have been satisfyingly fruitful. There have never been B-type avocado trees flowering within 100 feet. Commercial growers also often plant these varieties in particular in blocks without B-type varieties added for pollination because they don’t find it necessary.

There’s a lot more to the cross-pollination topic, but I’ll leave it there for now.

I think you’re right about Lamb and Sirprize being naturally smaller than Hass and Reed. And that can certainly be an advantage for some settings.

HI Greg,

Love your site and youtube channel. Its an incredible resource for all us backyard growers. I live La Jolla near the cross. I planted a Sir Prize about 5 years ago. Its about 8-10 feet tall. It seems to be doing ok but it has not produced all that well so far. Last year it had about 8-10 delicious avocados. This year there are only 3 or 4. Right next to it is a small Reed I planted 2-3 years ago that is still too small to produce. Could the Sir Prize still end up being a decent producer or do you think its always going to be light on the production? I have a spot for another tree and per your suggestions I could put in a Hass. I could also take out the Sir Prize and do a Pinkerton or Fuerte. The Sir Prize is in the prime spot. The other location is behind a trellis and gets less sun. What do you think? My thought was to leave the Sir prize and plant a 15g hass in that last spot.

I live in 92120. Fuerte does not do well here. I planted a Fuerte and my neighbor planted 2 of them. Hardly any fruit for years. Finally, I cut one back and grafted Hass to it and it produces hundreds every year. Hass is without a doubt the best producer and I picked them off the tree until Sept.. It is Oct 4th and I have one Hass left in the fridge and it is still good to eat. I have some Reeds on my trees and they will be gone this month. Reed is a fantastic avocado! My Mexicola Grande tree grew fast and has a 5″ dia. trunk by there are some issues people should know. The seed is massive, the texture is watery or low oil, the taste is good, there are strings, and the worst part is that most of the other food in my yard is gone, so the rats attack the thin skin Mexicolas and chew on most of them. Therefore, I’ve cut the tree back and grafted Reed and Nabal to the new shoots off the trunk. I have not had a Nabal yet, but from what I read it should be ripening now and is high quality. Being on a hillside I can’t remove the ivy, so the rats and voles have a super highway system installed. The thicker the skin, such as that on Reed, the better.

Thanks for this, Richard. Fuerte was a gamble for your that didn’t pay off, eh! I wish Fuerte were more reliable. It’s a shame.

Some people forget that Mexicola and Mexicola Grande are two totally different varieties. I’ve never met anyone who doesn’t like the taste of the little Mexicola; but I’ve never met anyone who raves about the taste of Mexicola Grande. I’ve never eaten M.G. so I can’t compare.

Sounds like Nabal will suit your situation. It has about the same season as Reed but an even harder skin. Should be far less vulnerable to the rats than Mexicola Grande.

Richard – I don’t know how high rats can jump but you might try trimming the lower branches a few feet above the ground and then installing a tin or alum. barrier around the trunk.

Hey Greg! quick question…should I have blossoms on my avacado tree?

Hi Greg, have you tried or are growing Carmen Hass? Its supposed to fruit 2 to 3 times a year. I have a small one in its first year so I can’t confirm on when and how many times a year it fruits. This would be a great variety to extend your avacado season

Hi Sergio,

I am growing a single Carmen tree, but thus far it hasn’t bloomed in the off season (around now, fall). I also know other Carmen trees located inland like me and they also don’t get it. These trees are in Redlands and the San Joaquin Valley.

On the other hand, I know of Carmens closer to the beach that do get off-bloom. Carmen trees in Irvine do, for example. And just yesterday I visited a grove with many Carmen trees in Somis (near Ventura) and they were flowering away. That grove is part of a rootstock trial so data on the harvests of all the trees has been collected since its planting in 2012, and the researcher said that the Carmens there produce nearly the same as the GEM and Hass trees in the trial, overall. The difference is that the Carmens split their yield about 50/50 between the spring crop and the fall (off-bloom) crop.

So yes, Carmen would be an excellent variety to have in a yard that is not too far from the ocean because it would have that expanded harvest season.

How far from the ocean will Carmen perform (and set fruit from) a fall-season bloom? I don’t know. The farthest I know of is Irvine, which is approximately 10 miles from the ocean as the crow flies. I am 20 miles inland, plus up in the foothills, and I don’t get the off bloom.

Hi Greg,

Did a google search on the Julia and this page came up because someone commented about it being for sale at Subtropicana.

I usually seek out local bay area avocados as you know but when I when I lucky enough to come across this rare Gem I immediately bought it. Can you tell us anything about it? I know it is a seedling of Nabal, is supposed to be both excellent and sweet, large tree (I read), type A with a large seed and was formerly unreleased. Was wondering if you have had any experience with this new previously completely unavailable variety. I figured you can’t go wrong with a seedling of Nabal. Am I correct? Thanks for all you!

Greg

Greg, thanks for bringing this conversation to the table. My wife gives me a hard time, but slowly I’ve managed to get her to buy into the year round Avocado journey. I’m looking for advice on additional Avocado tree recommendations to complement what I’ve started. I have (Reed, Lamb-Hass, Fuerte, Sir-Prize, Pinkerton, Bacon, Nabal, Holiday, Mexico, Jim Bacon (Impulse Buy) and 2 Hass). I have on my Radar (Kona Sharwil (25% oil content?), GEM and now Carmen Hass) I started this journey using a Calfiornia Avocado Harvest Season chart by Hofshi, Bender, Frink and…. Alder! I’m on a hillside in Whittier and I have room for a few more, looking for any ideas on trees that give me a better chance of having avocados year round. Thanks

Also – I read about honey water yesterday and now see someone posting here about it. I also heard it stunts the growth of the tree if it gets enough fruit to prevent growth. Which made me curious if when the tree gets to the “Right Size” is Honey water a gift both in giving fruit as well as minimizing tree growth and pruning needs? Seems interesting. Thanks for your time!

Hi James,

I can hear your wife’s comments now — because they’re the same as my wife’s!

It looks like you have everything covered with those varieties. You’re doubled up on every season. And on a hillside in Whittier you should get good production from B types because spring days and nights will likely be warm enough.

Sharwil, GEM, and Carmen are all good ideas for additions. Gwen and Jan Boyce are a couple of other good ideas. All of these varieties have roughly spring or spring into summer harvests, and all taste great. GEM and Gwen are likely to be slightly smaller in stature than the others, if that matters. Sharwil is the only B type in the group.

I have seen what you describe: young trees setting a lot of fruit and not growing much. Often the same varieties that do this also get the reputation as being smaller trees, but part of that is due to their heavy production preventing much foliage growth, year after year.

As a quick example, I’ve got a Pinkerton tree that never grew much until this summer. It barely flowered this spring, set zero fruit, and then took off growing. I’m actually happy about this because next year it will be big enough to finally handle a real crop.

Thanks Greg, found a Kona Sharwil 5 gal and went with it, Hawaii seems very proud of these Avocados and hope they are all they say they are. I still have two spots left and will put the thinking cap on before I pick and plant those. Also wanted to mention I just found out the house I sold a few years back in Downey, CA had the huge avocado tree cut down as well and the people replaced it with concrete. Madeline, (40 year owner that I bought the house from in 2012 would have been devastated, she as 92 when I bought the house, ate avocados through the year and was sharp as a tac) She claimed to have planted the seed herself only to be told it will never give fruit. That tree was a huge, 40 foot tall with two dominant branches, 2 foot thick each. The tree would set flowers twice a year and the primary crop was ripe early spring giving heavy fruit every other year. I believe it was a fuerte descendant given its growth patterns and what I have just learned on alternate bearing. Either way, sad to see the people didn’t respect the tree as it deserved.

Greg – Where did you buy that GEM tree?

I haven’t been able to find any for sale.

Hi Dal,

I bought my GEM trees from Subtropica Nursery in Fallbrook: https://www.subtropicanurseries.com/

I have not eaten a fuerte in over 40 years. My favorite. I can taste it now. Yum!!

I will be planting 1 fuerte among 30 other varieties in a year on Hawaii. I’m getting scion wood from epicenter for 13 of the varieties. They have just a license to ship trees in California. I was so happy to hear that they could send the wood.

Hi Michael,

I wonder how Fuerte will do at your place on Hawaii. I’ve never heard how Fuerte performs over there. Hope it does great and tastes like you remember!

Good to hear that Epicenter can ship scion wood to you, at least. You are going to have an amazing variety collection. Please keep me updated on how it all goes.

No worries. You’ll be first to know. This will be fun. Much to learn.

I live in north east Florida and able to grow Haas avacados, and the typical carribean avacados. Occasionally gets 25degrees in winter, usually 28 the rest of winters. Anyway, I amlooking someone who wii ship to Florida, Specifically,Pinkerton, lamb and or Mexican, small black , thin skin one. Thanks Dean

Hi Dean,

Are you interested in getting fruit or trees?

Comment #2

Greg – Great topic and I like your choices. However I will suggest three other factors should influence your choice. 1) Where is your location. i.e. Distance from the ocean. 2) the size of your yard, it has to be big if you want a Fuerte. and 3) What variety if any do your neighbors have.

Here in Sylmar we have some sort of brown tip disease that has been killing our olive trees so I have been planting avocados as a replacement. It used to be freezing that helped me decide what variety to plant but now it’s what variety will stand up to these new heat waves and not drop it’s fruit. Pinkertons seem to do well here and my young Reed seems to hold up so that’s my choice for this area.

You don’t seem to be too keen on the Stewards and Mexicolas but I think any avocado is better than no avocado, I love my Steward and those Mexican leaves are great in a slow cooked beef stew. I cooked a pot yesterday. and if you can believe this, the dried Mexican avocado leaves sell for an outrageous $6.00 for 4 oz ($24.00/lb) on the internet.

Those “Ripening Charts” don’t seem to be 100% accurate for all areas or varieties

I just planted a Mexicola because a tree in the neighborhood had it’s fruit mature last month (Sept.) and my Stewart will mature at the end of this month (Oct.).

I’ll do another comment on why a California Mexicola is better than a spoiled little Hass from Mexico.

Calavo should get it’s act togather and sell us what we want, not what they want.

Hi Dal,

Thanks for all of this. It is unhelpful that every harvest chart — including my own — is not accurate throughout California. Maybe someday I’ll try to make one that includes separate harvest seasons for different areas. The California Avocado Society used to make similar charts, but only for a few commercial varieties. They split the avocado-growing areas of California into at least five climatic zones.

I was up in Ventura the other day, and an avocado grower told me he doesn’t pick his Reeds until September at the earliest. Many of my Reeds are overmature in September. I’m farther south and inland, and so much hotter, compared to Ventura. My harvest chart is just plain wrong for him.

Hi Greg! I have a little cado /wurtz that is extremely low in yield like 1-2 avocados per year after being in ground for 7 years. I think I read on your post somewhere that this is a low yielding type. I originally got it thinking only about size control of the tree. I kind of would like to pull it out due to low productivity But thinking that would it make sense to graft Hass onto this and control the size of the Hass tree and also significantly increase my yield?

Jean – I planted a Wertz about 40 years ago when we moved into our new house.

I remember it took a long time before I got any kind of avocado crop. About the time I learned to stop raking up those fallen leaves, avocados started showing up. I don’t know if it was “time” or “leaves”. About 11 years ago I planted a Stewart on the other side of the house the Wertz crop seemed to double. My problem with the Wertz now is it does not like heat waves. The whole crop dropped when we had that heat wave last year.

Hi Jean,

I just saw a Wertz tree the other day that was planted as a five-gallon tree in 2015, and it had 21 avocados on it. It was about as tall as a person. The owner told me this was its second year fruiting. He does have three other avocado varieties growing within thirty feet of this little tree.

I don’t know much about the productivity of Wertz in general though, honestly. I don’t grow it, and I haven’t seen many mature Wertz trees in different locations in person.

You could certainly graft Hass onto the tree, but I wouldn’t count on the Wertz rootstock (or interstem, really) having a dwarfing effect on the Hass. I’ve been told by someone very knowledgeable that this has been tried before with other small-growing varieties such as Holiday/XX3, and they were surprised to find that the Hass scion wasn’t dwarfed. Regardless, you could always prune the Hass to the size you want.

An alternative to grafting would be to plant a Hass right next to your Wertz.

My second reply on the Wertz:

This summer there is over 100 avocados hanging on my Wertz.

Squirrels are a big problem, with a good air gun I made a great batch of

Brunswick stew last week

Great article on year round avocados

We are moving to a house in Vista, Ca. early November 2019.

I have the following avocado varieties in pots that I hope to plant them once we move to the house.

Fuerte, Pinkerton, Mexicola. (big box stores), two Gem and one Reed from Subtropica in Fallbrook,

I wanted to add Lamb Hass but after reading you article I am considering another variety to replace the Mexicola.

Any suggestions? Also since it will be November I am thinking that I should wait until April next year to plant them?

Thoughts?

Any possibility in visiting you home where you have Many varieties growing?

Thx.

Eddie Munoz

Hi Eddie,

Great you’ll be growing avocados in Vista. That’s a nice place to grow them. I’d plant them as soon as you arrive. Most of Vista is very mild. Do be prepared to protect them if we get an unusual cold spell in winter though. See my post on protecting avocados from cold: https://gregalder.com/yardposts/protecting-avocado-trees-from-cold/

Mexicola is unique. I don’t know of another avocado that tastes good and ripens as early. In that way, there’s no replacement for Mexicola’s harvest window.

Yet eventually you’ll probably be able to get your Reeds or especially Lambs (if you get one) to hang into fall and connect with the beginning of the Fuerte season.

I let my avocado trees grow to different heights and widths. It just depends on where the tree is. I don’t have a commercial grove; I have a regular yard — although it is somewhat large and hilly and rocky. Some trees I keep shorter so they don’t affect views and others I keep narrow so they don’t overtake adjacent trees.

I hope to invite some folks over someday soon, but we’re not quite ready for it yet. Thanks for the interest. I’ll let you know when we’re ready.

Great. You seem to be very a knowledgeable and a very educated/experienced DIY gardener.

Any advice on mango trees?

I have 5 that also need to go into the ground and I am wondering whether to plant now or spring.

Thx.

Eddie Munoz

Thanks, Eddie. I’d plant the mangos now too, unless you think you live in a cooler spot (like at the bottom of a canyon) and you’ll have a hard time protecting them in a cold spell this winter. Mangos are a bit more sensitive to cold than avocados. Still, baby mangos make it through all but the coldest of nights where I am in Ramona, which is colder than anywhere that I know in Vista.

Thank you Greg. The property is sort of a hilltop with a slope. Where I hope to put the trees. Both avocado and mangoes.

Hope all is well with things in Ramona. With these fires

Hi Greg,

I just bought a 5 gallon Hass and was wondering if I should wait till spring to put it into the ground or if I can plant it now?

Thank you,

Justin

Hi Justin,

Plant it! I planted a couple avocados last week. This is a great time for it.

I have a sir prize, lamb hass, and an edranol in the ground. The extremely large pepper tree that killed my Nabal has been removed so I’m looking at planting one or two trees there now. Ideally one that gets tall so as to block views down the hill like the pepper tree did would be nice. I know nabals get gigantic in time. Do you have any other thoughts? I’m considering a Stewart to fill the fall gap but do they get huge? Pinkertons are yummy but a tall tree is critical. Can anyone advise me on trees that are more prone to height as opposed to spreading?

Hi Bob,

I’ve never seen a tall Stewart, but maybe some exist, maybe it depends a bit on the rootstock.

Pinkertons are also not the tallest of avocado trees, as far as the ones I know.

Nabals definitely get big. Hass get pretty big. Fuerte trees spread a lot but they can also ultimately get tall too. Bacon trees are more vertically oriented in general and get very tall. Reeds like to grow mostly upward.

Bob – I have a 11 year old Stewart growing here in Sylmar with about 60 avocados just starting to mature. It is not a big tree possibly only 12 to 14 ft high. I think it’s a great tree if you have a collection as it tastes great to me and fills a spot when bad Hass avocados are imported. One other thing, being a Mexican variety the leaves are great for flavoring in BBQ and Slow Cooking

Bob – I’ve had a Stewart here in Sylmar for over 11 years and it’s only about 10 or 12 feet tall.

As a bonus you geet great flavoring when you use those Mexican leaves for cooking & BBQ.

Greg,

First I would like to thank you for the wealth of information you provide on growing avocado trees. Thanks to your recommendation I have replaced 5 year old Hass tree which never gave me a single fruit and was constantly infested with persea mites with Lamb-Hass. It has been in the raised bed for 3 months and watered mostly with rain water. Not a single leaf tip burn, good a foot of new growth and not a single leaf infested with persea mite. In comparison I also have 5 year old Bacon with 22 fruits and about 10%of leaves infested with mites. The Lamb-Hass also performed better than bacon during the last week heat wave of 96-98°F for several days and about 23% humidity. Bacon had drooping new leaves in the afternoon even when watered in the morning and with 6-8” thick mulch all around the tree. Lamb-Hass didn’t have any shade and not a single leaf was droopy.

I’m considering to add one more avocado tree to my yard of GEM variety for spring harvest. Unfortunately it is very hard to locate the tree in nurseries and there is very little information available on its resistance to persea mites. You have mentioned that you have a GEM tree. What is your experience and recommendation?

Thank you in advance for your help. I will be building a 36” high raised bed of 10ft dia because of heavy clay soil I have and would like to make a final decision on the tree within the next month or so.

Hi Paul,

Glad to hear the Lamb tree is growing well for you. I have noticed that my own Lamb seems unappealing to persea mites as well.

Depending on where you’re located, Subtropica Nursery in Fallbrook might be an option for finding a GEM. I don’t know much about GEM and persea mites, but I can say that my GEM trees have never had any, nor have any that I’ve seen, and the GEM patent claims “Moderate resistance to Persea mites is exhibited.”

I went by Subtropica a few days ago. They had many GEM avocados in the 3.5 gal sleeves on a pallet ready to be sold. They also had a couple varieties that I’ve never heard of like “Julia” and “mayo”.

I hadn’t known they were propagating Mayo. Good to know. Thanks, Walter!

Descriptions and photos of Julia and Mayo can be found at the UC Riverside avocado variety page here.

Thank you Walter for the tip.

Walter went to Subtropica nursery yesterday and purchased Dusa cloned rootstock GEM avocado tree for $32 in 3.5 gallon sleeve.

Got home and re potted to a 5 gallon container for the time being as my planned raised bed is not ready yet.

Thank you again for the tip. Hopefully in a month time it will go to the ground. Tree looks healthy and many new shoots. We should have a warm November so I think the tree will grow quite well in the pot.

Good luck. I didn’t notice the dusa rootstock but chasing my 5 year old at the same time as I was looking.

Thank you very much for store location. I’ll be buying the tree sometime the next week. Also want to thank you for the link to Gem avocado patent properties.

I’m in the process of building a raised bed about 90 sq. ft area about 3 feet deep that will be built on a mostly clay soil. I’m planing to keep top 12″ of existing lawn sod soil and mix it 3:3:3: with sandy loam, mulch/compost/horse manure/pumice mix. This is going to be a major time and money investment for a single tree but I’ll be soon 65 and don’t have time for another trial if things should go wrong. I live in La Mirada about 15 miles from the coast. We only get about 2-5 days with temperatures over 100 and I think that persea mites like this micro climate quite well. Definitely the Hass tree was clearly very susceptible.

Interestingly neighbor 300 ft away has at least 35-40 year old avocado tree planted in very small raised bed (16 sq feet) and the tree has no leaf tip burn, at least 300 avocados of pear shape and no persea mite infestation at all. Very puzzling. Most likely due to the fact that it is a mature tree with well established root system (definitely past the raised bed) and most likely not fertilized much. I think i may have had fertilized the young trees too much due to some chlorosis shown near the leave veins. These symptoms were more pronounced on Hass and to the lesser degree on Bacon. I have applied about a pound of zinc sulfate around a Bacon tree and all new leaves are now deep green. Lamb Hass so far is perfect in every way. The real test will be mid winter after some heavy rains.

Regards,

Paul

Greg,

one more thing on a subject of Persea mites. I have a single grape vine Monukka on north west side of my house and have noticed that 80% of its leaves are infected with spider mites. That may be the source of my yard mite infestation even though the avocado tress are on the South side of my property and about 50ft away from the grape. I’ll be pruning the canes in few weeks and thoroughly spray the canes with dormant oils to see if i can get rid of the mites for good.

Hi Paul,

My guess is that your effort building this raised bed for your new avocado tree will pay off. I helped a friend plant some avocado trees in a similar way earlier this year. He had killed a handful of avocado trees previously without planting on mounds, but now these trees on mounds are flourishing.

There are definite differences among varieties in terms of vulnerability to persea mites. I was at a friend’s place last week and saw that his Ardith tree was infested with persea mites while other varieties nearby had few to none.

From the UC IPM page on persea mites: “Persea mite is most damaging to Hass, Gwen, and a few other varieties. Esther, Pinkerton, and Reed are of intermediate susceptibility. The Bacon, Fuerte, Lamb Hass, and Zutano varieties are much less affected.”

For mites generally, they like dusty leaf surfaces. I live on a dirt road. Whenever I have any kind of mites on any plant, I usually get decent control from simply spraying down the plant with water occasionally to clean the tops and bottoms of leaves. I do this to tomatoes and potatoes, for example, in addition to avocados. I don’t know that this will work for you, but it’s something to try.

My small Gem that I purchased from subtropica developed a persea mite situation. The new growth now is fresh and clean while the old leaves with mite activity are falling off. I used a bit of neem that seemed to help.

Hi Greg,

I love your posts! What do you think of pairing a Holiday avocado tree with an existing Hass? Your chart would seem to suggest that would be a good match for an almost-year-round avocado harvest. I live in the Inland Empire (Redlands).

Thanks!

And is there an advantage go planting two type A trees near each other so they can cross-pollinate or does it not make much difference? Thanks for sharing your wealth of knowledge!

There is definitely an advantage to planting two type A avocado trees near each other. So any other type A avocado next to your Hass will increase pollination somewhat because even all A-type avocado varieties have slightly different schedules of flowering openings. It’s just that a B type has far more potential to increase pollination of your Hass compared to another A type.

I’ve noticed this while watching my own trees, but there’s real evidence for it from lots of experiments. For example, if you look at the results of this cross pollination experiment, you see that the many B types had a greater influence on Hass yield compared to the only A type (Harvest): https://ucanr.edu/datastoreFiles/234-2475.pdf

Hi Mika,

Thanks! In terms of harvest seasons, Hass and Holiday complement each other well. But unless you’re set on Holiday, I’d prefer another late variety such as Reed or Lamb because they are tougher and more productive than Holiday.

One other thing that you might consider is the style of growth that the other tree has compared to your Hass. Hass trees are vigorous, and they grow both up and out. Holiday trees, on the other hand, weep and crawl on the ground like bushes unless you diligently stake them up, and even if you stake them they will never grow at the fast rate of a Hass. Just something to keep in mind.

Hi Greg. Do you know anything about Leavens Hass? Thanks!

Hi Ryan,

Not much, unfortunately. Brokaw Nursery in Ventura County propagated it for a while although I’m not sure if they still do. If you really want information about it, I’d contact them.

The genesis of Leavens Hass seems a bit shrouded in mystery. It’s unclear to me whether it’s a Hass seedling or a Hass sport. My guess is that it’s a sport. Apparently, the location of the mother tree has been lost.

What I have read is that Leavens Hass matures slightly earlier than Hass, the fruit has a bumpier peel, the tree has larger leaves and is slightly bigger. But these differences are all minimal and would only be noticed by someone with a lot of avocado experience. So I’ve read. See this information about it: http://avocadosource.com/forum2/thread.asp?m=1256

It so happens that I grafted one Leavens Hass earlier this year but it failed. I’ll try to graft again next spring and maybe I’ll eventually have something firsthand to say.

Hi Greg,

Thank you so much for such a wonderful blog! I would love, love to have avocado trees in my yard but have not had much success mostly because my wife and I, both being small business owners are either working to death or too exhausted to work the yard and deal with squirrels that carried away the one avocado that came with a Haas tree we planted 10 years ago (that tree died after 1 year).

I eat avocado every day and like varieties so I journey out to Jacinto Farms in Mentone from my 90064 zip to buy whatever they have in season; we got dozens of huge Reed and Haas earlier this year but they had no avocados when we called last month. I can barely wait for Pinkerton and Fuerte (two of my favorites) to show up. I try to get from my local Farmer’s Market in Mar Vista but I have only ever seen (other than Haas) Fuerte and Bacon (not a fan). There was a lady with large nice Pinkertons at the Torrance Farmer’s Market a few years ago and I loaded up then but she’s gone!

I imagine there are others like me struggling to find good consistent supply of locally grown varieties (that is not Haas) year round. Do you have any recommendation of farms, stands and/or individuals selling various varieties that I could use to form a personal supply circuit? Geez, GWEN, Nabal, Lamb, if only I can get my hands on some of them!!

Any lead you can provide to temper this avocado fever would be greatly appreciated.

Hi Greg,

Your blog is great and so helpful. Thanks so much for putting it together. Do you have any experience with planting 3 avocados in one hole (e.g. Pinkerton, Fuerte, Hass)? I have seen some people mention that this is successful but haven’t seen any videos or photos online of this. I am just wondering if people are saying it’s a good idea but I would like to see some evidence that it works well. I have a small area in my yard which would be good for a 12 x 12 or 15 x 15 max tree. But the 3 in 1 option sounds great if it can actually work and be pruned for size control. Thank you!

Hi Jeff,

Thanks! I have a little bit of experience with that kind of tree. I do have one actual 3-in-1 planting, where I put three avocado trees in the ground about a foot apart, but it’s only a year old.

Otherwise, I have experience with 2-in-1 plantings that are mature and multi-graft trees (on one trunk). My opinion about all of these is that their success mostly comes down to your own pruning maintenance. It’s simple: you just have to make sure that the slowest growing variety doesn’t get overwhelmed by the faster one(s).

In your example of Pinkerton, Fuerte, and Hass, you’d probably be pruning back the Fuerte and Hass to make sure they didn’t shade out the Pinkerton. In that case, I would also not allow the Pinkerton to hold fruit for the first few years so it could grow more vegetatively (although you could still let it flower in order to pollenize the Fuerte and Hass).

I’ll also add that I know of an avocado farm that does 3-in-1 plantings with their pollenizer trees. They grow A-type varieties (such as Hass) for the fruit, and then they put in 3-in-1 plantings of Bacon, Ettinger, and Zutano (all B types) here and there to provide pollen. They keep the 3-in-1 trees pruned so each variety takes up about an equal portion of the canopy, and they keep the whole 3-in-1 canopy pretty small because they don’t need a big tree to perform that pollination job. (They use three varieties because each variety blooms at a slightly different time.)

In short, it’s absolutely possible to grow a good 3-in-1 avocado tree, but you have to be disciplined about the pruning, and you have to have the patience and foresight to be willing to hold back the faster varieties for the sake of the slowest variety — and there’s always a slowest variety — in order for the unit’s long term success. This is not a technical challenge, but it can be an emotional challenge, in my experience.

Hi Greg,

Thanks for the explanation! How often and during what time(s) of year do you recommend doing the pruning? Do you think 3-in-1 would fit in a 12 x 12 area, and if so, how large of a size maximum would you allow each the trees to grow to? Can you explain more about what you mean by an emotional challenge? Is it just hard to see each of the trees getting a sizeable amount pruned off them? I’m curious to learn more about what inspired you to do the 3-in-1 last year especially as I haven’t seen much info out there about people doing this (just recommending that others do it).

Thanks again,

Jeff

Hi Jeff,

I planted my little 3-in-1 for two reasons. One, I had a bunch of small trees that I didn’t have enough space allocated for as individual trees. And two, I wanted to experiment with a 3-in-1 tree myself because, as you say, people talk about doing it but I’ve never seen anyone document it (besides the farm I mentioned above).

It’s just hard emotionally to keep cutting one or two of the trees back because one of them is growing slowly. It tests my patience anyway. I once had a pair of trees, a Hass next to a Sir-Prize, and I had to prune back the Hass so many times so it wouldn’t overwhelm the Sir-Prize. That meant less Hass fruit, for one, which was irritating.

Looking back, I probably could have managed that pair of trees better through earlier, smaller pruning. This is what I’ll do on my 3-in-1.

With such a configuration, I think it’s best to orient the growth of each of the trees primarily vertically at first so I’ll be removing any side branches that are anywhere near as thick as the main trunks. After they are around five feet tall, I’ll allow more side branches that grow away from the other trees. I’ll keep the inside of the planting mostly clear.

The pruning will happen all the time throughout the year in small pinches with my fingers or cuts with hand pruners. Hopefully I can stay on top of it like that and never have to make a big cut. But we’ll see. This is all a plan and rarely do things go perfectly according to plan.

My 3-in-1 has more like 15 feet in diameter to spread, but you could certainly keep such a planting to 12 feet. If you chose varieties that were all more vertically oriented and similar in vigor, the job would be easier.

Lamb and GEM are two varieties that don’t spread much and aren’t so fast growing, in my experience. Bacon is another upright variety that has a complementary harvest season but it grows relatively fast so you’d probably have to prune the Bacon back if you used that threesome.

Greg:

Wow, I just found this blog and realize that you live right here in San Clemente, as I do. I recently planted 3 six foot tall avocado trees in half wine barrels and am really looking forward to when they start bearing fruit. They are in containers because we might move within the next 4 or 5 years and I would want to take them with me.

I have a Bacon, a Holiday and a Haas. I am thinking I would like to plant one more and am considering a Reed.

Any thoughts?

Eric

Hi Eric,

While I do pass through San Clemente often and have friends who live there, I live down in San Diego County.

I would put those trees in the ground if you can. Avocado trees are harder to keep happy in containers than in the ground. If you move in a few years and have to leave the trees, consider them your training trees. At the next place you’ll be able to grow new ones better, and you might find that you want to try different varieties.

I say this from firsthand experience. I spent four years at a rental property growing avocados both in the ground and in containers (because I thought I would take those ones with me someday). My trees in the ground all grew better.

When I moved to my current house, I had learned a lot about growing avocado trees from those previous trees and the new trees I planted here grew much better because of those years with my “training trees.”

Reed would make a good addition to your collection, as its harvest season is after Hass. Reed’s season is similar to Holiday, but I’ve never seen a Holiday tree make much fruit so I wouldn’t worry about having too much fruit at that time.

Is my Bacon Avocado a good cross pollinator for the Hass, Holiday and Reed? Not sure if the Bacon flowers at the same time as the others…..and if it doesn’t then I assume it will not cross pollinate??

Hi Eric,

You’re right that the bloom has to overlap for there to be cross pollination. You can’t be sure because every year is a little different, but usually Bacon does overlap somewhat with all of those varieties. Reed is the latest bloomer but it also sets fruit well without a pollenizer.

Hi Greg,

I bought a dwarf avocado tree (tag said dwarf avocado/hybrid dwarf) from Home Depot a couple years ago and can’t figure out which one I have. The tag didn’t specify (just that it would be 6-12 ft tall, 5-10 ft wide), nor was I able to get further info by the product ID on the tag. But I’m guessing that I may have either the Little Cado or possibly Holiday, given that it’s supposed to be a dwarf? It’s growing a little top heavy/weepy but no fruit yet as expected. Are there any distinct characteristics I can look for in order to determine which type I have? And/or could it possibly be another type other than Little Cado or Holiday?

Hi Stacey,

This is so annoying. I wish the nurseries and Home Depot and other garden centers would stop doing this. What you almost certainly have is a very old variety called Wurtz, which originated in Encinitas in San Diego County. Read more about the Wurtz avocado variety by entering the name into the database search bar here: http://www.ucavo.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/Panorama.cgi?AvocadoDB~form~Search

Hi, I love your Yard Posts! So much valuable information and glad I found it. I recently moved (LA County) and am excited to be planting a couple avocado trees! Trying to figure out the best varieties/combinations, and want to include a B type. I’ve already got 2 Hass. I’ve made space for 2 more trees, and leaning toward a Sharwil and Pinkerton. But I also see that the Holiday Dwarf season will apparently cover more months of harvest when the Hass is out of season, tho I haven’t found much info about Holiday Dwarf. Anyway, I would like to have maximum months of harvest without all A types. Here are my questions:

1) Regarding the A-B flowering types, do all types flower at the same time, or do they flower at different times based on the variety? For example, if the Sharwil flowering season does not overlap the Hass and Pinkerton, what’s the point (other than it’s still a good tree)?

2) What would be your recommended varieties if you were in my position, without planting a Fuerte?

Keep up the good work and stay healthy during these times.

Cheers,

Lucas

Hi Greg,

I’m looking at getting a summer variety to add to my GEM avocado. In your opinion, which summer avocado tree is easier to keep at 12 ft? Reed or lamb?

Hi Tin,

Lamb is a bit easier to keep down in size; Reed is somewhat more vigorous. Yet I keep my Reed to about 12 feet so that is also very workable.

Hi Greg,

I enjoyed reading your articles. Very informative. I am interested in planting avocados but I’m in zone 7b, Marietta, Ga. I like the idea of three trees: a Hass, reed, Pinkerton or Fuerte. Because of our possibility for low temps I’m assuming I can’t plant in the ground and need containers. I’ve considered rigging a lightbulb under a canopy or planting them close to the house for more protection but I’m not sure that’s reliable enough if temps drop to 10-20 degrees. Is it possible to grow in the ground here without needing to be worrying about them? I lost a 3 year old orange tree in a container from a surprise frost. I thought I might lose a few branches but it died completely.

What would you recommend for trying to grow in containers and bringing them in between November and March?

I’m intrigued by the idea of planting several trees in one hole, but would that work for a container? It certainly would keep our sunroom less jungle like.

I lived in Northern California for 30 years and miss citrus so much. I’ve just purchased a few and am going to try to make a go of it. A Meyers and Genoa lemon tree and am about to order a eureka lemon and Washington navel orange. All of which I assume I’ll need to bring inside for protection. So any strategies for condensing and growing tips would be appreciated.

Our sunroom has a peaked ceiling to about 14 feet but about 32” doors to try move them thru. I bought dwarf citrus to hopefully have them produce more at a smaller size. I mention it in case there is a target height I should go for for free health and production.

Do you recommend dwarf trees over standard when containering or trying to keep them short enough to harvest?

Thanks so much for your articles, replies to posts, and advice. It’s fascinating. Before a few weeks ago I never knew there was so much info about avocados.

Cheers,

Sean

Thanks for writing, Sean. I know that if I were in Georgia I would also be trying to figure out a way to grow some citrus and avocados. I only wish that I had more firsthand experience to share with you about this type of growing. But let me give my best shot with some educated guesses.

If I were you, I would try to grow trees of the best varieties, on vigorous rootstocks, plan to train them more vertically so they can fit through the doors, and plant them in containers.

Choosing the best varieties means not looking for “cold hardy” avocado varieties or just kumquats for citrus (which are hardier than most other citrus). For avocados, if I could find the trees, among my first choices for varieties would be Gwen, GEM, Lamb, and Carmen because these varieties are all delicious, precocious, can easily be trained vertically, and they are “efficient” (they produce a lot of fruit for the size of their canopies). But also, the varieties you mentioned could work. I might also add a B-type variety in there just to get maximum pollination and fruit set out of the other trees, which will also help to keep the canopies smaller. Fuerte could work there, as could Sharwil.

I would rather grow on vigorous rootstocks than dwarf rootstocks. My experience is that vigorous rootstocks are more forgiving of less-than-perfect watering and soil conditions. I would want a tough rootstock, not a wimpy dwarf rootstock. I would rather do the size control through pruning than spend years watching the trees grow slowly. Having the trees in containers will dwarf the trees somewhat anyway.

I would grow each tree in its own container, and into each container I would put a stake that I’d tie the central leader of each tree up onto. This would help to train it vertically, and later it would help support the fruit load.

Those are some of the things I would try, based on my own experience growing avocado trees temporarily in containers before putting them into the ground, and based on the reports of others who grow avocados in containers. But as I said, there isn’t much firsthand experience here so don’t take any of these suggestions too seriously.

If you end up getting started on these trees, let me know and I’ll point you to some information about containers and mixes to fill them with.

Hi Greg,

Thank you for your reply! I like your educated guesses. I was thinking dwarf stock might mean that I would get fruit sooner because the root was 1-2 years older than the graft. All I know at this point is what I’m reading though and I did notice people list root stocks as A letter and a number and I don’t know anything about that yet.

How do you find a tree with a vigorous root stock? I’ve been using the web to find trees as nobody has them here.

I’ll also take tips on the dirt mix. I read about keeping it dry with recommendations on citrus mix. I’ve heard varying opinions on whether to fertilize or not. But I can wait till I find some trees. I read your affinity for the Fuerte but read people say they are fussy producers and I wonder if the large fruit wouldn’t jive well on a smaller tree. Still I’m fascinated to try one. You like the other B tree types taste too? I’m on a phone so it started with the S.

Now I’m hoping I didn’t choose poorly on my dwarf honey crisp and dwarf nectarine trees. If you have soil mix tips for my lemons, honey crisp. nectarine, and 3 in 1 cheery tree those have been ordered.

I’m eager to order avocados in the next week.

Thanks again!

Sean

Hi Sean,

When I was talking about vigorous rootstocks I was thinking about avocados. As for citrus and others, dwarfing rootstocks seem to perform fine for trees in containers.

I would read about what people have to say at Tropical Fruit Forum as to container mixes for citrus: http://tropicalfruitforum.com/index.php?board=12.0

I would also read the advice at Four Winds Growers: https://www.fourwindsgrowers.com/pages/growing-dwarf-citrus

Both Sharwil and Fuerte taste excellent. You could not be dissatisfied with the taste of either.

That sounds good on the forums for citrus. Thank you!

Can you tell me more about how or where to find those varieties with vigorous root stock? Do you mean just not dwarf root stock or were you suggesting a particular grafted root stock I should search for that is more vigorous by design?

Thanks again and cheers,

Sean

The good news is that all of the avocados grown by the main wholesalers use vigorous rootstocks so there’s really no need to search for a particular rootstock.

Hello Greg,

I really enjoy your posts and I go back and reread them and pick up new tips each time. As I was doing this on this article, I noticed that you mention in your revised list of preferred avocados for year round had Hass and Gwen for Spring. I was wondering why Gwen over GEM (which was a contender in the earlier listing in the article)?

Hi Vernon,

I’m glad you asked this because it made me go back and reread this post. The fact is that my experience continues to grow and my views sometimes change so I really appreciate being called to revisit posts.

GEM is certainly an excellent variety for spring, but for me GEM trees have been slightly weaker growers than Hass or Gwen. Also to me, the eating qualities of Hass and Gwen are slightly higher than GEM. So if I had to choose only two out of those three, I’d remove the GEM. But to be sure, GEM is an excellent variety, it’s productive and it tastes great, and it even has some qualities that make it a better choice than Hass or Gwen in certain situations (e.g., GEM is a more compact tree than Hass, and GEM turns black whereas Gwen stays green).

Again, this is where my experience stands now. I’m open to the possibility of shuffling the rankings in a few years.

Hi Greg,

I live 13 miles inland in Thousand Oaks with about 5-600ft of elevation. Much like you my A types (Hass, Lamb, Reed) are much more productive and happy. My Fuerte finally has flowers on the shaded side but will see how the set is. My Sirprize has 4 flower bunches on the 9 ft tree. Will it ever produce for me?or should I literally cut my loses and plant something else?

Thank you,

Walter

Walter,

The way I empathize! I grew a Sir-Prize tree for five years before cutting my losses and cutting it down. Even when my Sir-Prize flowered well it never set fruit. It was adjacent to a Hass that was setting boatloads of fruit. It’s possible that you also live in a climate that has nights as cool as mine and that’s also your problem with B types.

Sir-Prize trees can fruit satisfactorily in other locations. I have friends with Sir-Prize trees that get decent crops. I’ve also heard many people say that Sir-Prize trees come into bearing more slowly than some other varieties, such as Hass.

One University of California avocado researcher said that you can get good production out of Sir-Prize if you’re willing to wait until year eight. But I don’t know if that’s the case if your climate isn’t right for B types.

I’ve kept my Sir-Prize rootstock and turned it into a small pollenizer tree for my nearby Hass and Gwen by grafting on Bacon and Zutano. Maybe you want to do something similar?

Thank you Greg! Saw your link on girdling and I actually went to college with Paul Nurre! Small world. Wonder if that could stimulate the sirprize? When girdling do you do a complete ring or half rings an inch apart? Seen both methods online? My fuerte had a decent bloom, nothing like my reed or hass which look like they are made of flowers but saw your opinion of honey water and i have lots of ants so not sure i need any more. Lots of flowers falling off but no fruit set at the moment. Disappointed as i love fuerte fruit. Hope for better results next year. Last question for now 🙂 I made the mistake of leaving the support stakes on all my trees and saw your method of supporting. Will they ever be strong enough to remove supports? Thank you for your help and insight!

Hi Walter,

What a cool connection with Paul Nurre. I’m not very experienced with girdling as I’ve only started playing with it. Last fall I girdled a branch on my Fuerte and a branch on my Nimlioh. Neither branch has flowered much compared to ungirdled branches on the trees, but maybe my timing was wrong, or maybe the girdled branches won’t flower intensely until next spring. We’ll see.

I’ve certainly given up on the honey water spray. This year was my last to experiment with it and once again it has shown no evidence of increasing bee visits to flowers in a way that would cause pollination.

As long as the ties on the supports aren’t too tight, then the tree trunks will be getting stronger slowly but surely. If they’re so tight that they don’t allow the trunks any movement, then remove the ties and put new ones on more loosely.

Hi Greg,

Thanks for the wealth of information on your site. I have just planted a Sir Prize, Sharwil and a Lamb within a foot of each other. The Sir Prize is about 3 feet tall and the others about 2 feet tall. I may be close to year round avocado production if they do well. I have about a 12 foot by 12 foot area for these to grow in so I will need to stay on top of pruning. If these trees go normally, do you know what my challenges might be with this mix of trees? I live in east Long Beach about 4 miles inland. Thanks again.

Hi Kyle,

Thanks. Cool that you’re trying a three-in-one hole planting. I’ve seen them work long term, and I’ve been caring for a few similar trees lately.

The only challenge that I’ve found with such a planting in general is the pruning work. You just have to make sure that one of the varieties doesn’t get left behind and shaded too much by the faster growers. Nip back that vigorous variety (or varieties).

You never know for sure which variety this will be, especially if your trees are on seedling rootstocks. Out of your three, if I had to guess, I’d say the Sharwil will be most vigorous and the Lamb least vigorous, but you never know.

Hi Greg,

I have a followup to my post on May 9th. To briefly recap, I planted a “3 in 1” with Sir Prize, Lamb and Sharwil in the same hole. The Lamb seems to be struggling. It was the most sparse, fewest leaves of the 3 when planted about 6 weeks ago. It seems that generally watering per your guidelines is too much for the Lamb. The top leaves and branches of it are dying. Does over watering seem plausible? I’m really surprised that over watering might be a problem since they are on a mound over a foot high. We have somewhat clay soil in East Long Beach but I also mixed DG with it. Thanks for your great insights.

Hi Kyle,

Your description doesn’t sound to me like obvious overwatering. Could be, but not obvious. Truth test is to poke your fingers into the root zone of that Lamb each time before you water and gauge how wet it feels, especially compared to the root zones of the other trees that are growing better.

You might also poke into the soil at the base of the mound where the tree’s lower roots are. Is it remaining soggy down there?

Thanks for the reply Greg. The soil seems damp for a few days after watering around all 3 trees near the rootball. The mound is 8 ft diameter, almost as big as a pitchers mound so the roots are only near the top of the mound. I agree that it may be some other issue with the Lamb.

Hi Greg,

Thank you for all the amazing information! I feel much more confident that we’ll actually be able to grow avocado trees and get a harvest from them.

Based on your advice, we have gotten a Hass and a Reed and are trying to do an “avocado hedge” along a west facing fence. I would love to get a third to bridge the winter gap and be a “B” type pollenizer and I stumbled upon the fact that a Sharwil will hold it’s fruit on the tree (and still taste good) until the following year, so about March for Southern California. What do you think about using a Sharwil as the third tree? Yes, it would mean resisting the temptation of picking them any earlier but shouldn’t the Sharwil also increase the yield of the Hass and the Reed?

If it matters, we live in eastern LA county, either Sunset 18 or 19.

Thanks so much!

Hi Kate,

Thanks! Where are you exactly? Over near Pomona? I grew up in Glendora and know eastern L.A. County well.

I ask because Sharwil has the potential to do well for you unless you are at the bottom of a valley. They’ve planted a lot of Sharwils at Cal Poly on the warm, south-facing hill just south of the 10 freeway and these trees are growing well (interplanted with coffee bushes, actually) and they look like they will produce well, but if you’re low and in a colder microclimate you might not get great production from a Sharwil. B types in general tend to not produce so well with consistency if nights are chilly, as they are in some low spots in inland locations.

About Sharwil’s harvest season, this is something that I’m still getting a handle on for different locations in Southern California. But this year I’ve eaten Sharwils from a couple of locations in San Diego County and they tasted great starting in February. Here in May they still taste great, but the fruit seems to be nearing the end of its season and it’s starting to drop from the trees. In other words, Sharwil’s harvest season is a bit earlier than Hass (which doesn’t taste great until about April).

Also, Sharwils don’t hang on the tree as long in inland locations as they do close to the ocean (where I’ve eaten good ones picked as late as October). So for your location, my guess is that Sharwil’s season will be roughly January or February through the end of spring.

So with a trio of Sharwil, Hass, and Reed you would start with Sharwil in the winter, then start eating Hass in spring, and then switch to Reeds in summer. These would make a fine trio indeed!

Thank you so much for all that information! We live in La Verne near the 210 so the north side of town and in the foothills, so definitely not in the bottom of the valley. Sounds like Sharwil is a definite possibility then. Or I may give up the idea of having a B type and go with the Pinkerton that you recommend in another blog post. Decisions, decisions! I wish I had the room to grow as many as you have!

Thanks again – you and your site have been amazing!

Kate

Hi Kate,

Great! You live in a perfect place to give Sharwil a shot. And if I were in your shoes, I’d plant a Sharwil over a Pinkerton because Sharwil fruit is a small notch better in my opinion. You wouldn’t be disappointed in Pinkerton, but Sharwil is just a tad better to eat — doesn’t take so long to ripen, has richer color, peels and scoops better, and has a slightly fuller flavor.

Dear Greg, after gathering information finally i have answers, best avocados fit my area are Mexican verities and also i should try hass

Could you please advice ?

which is the most fastest way for propagation avocado trees (please consider plants or trees should be transported from USA to Republic Of Georgia via plane, and it will take at least total 10 days)? should i buy crafted trees in 3 gal post per verity and here propagate or should i purchase rootstocks per verity and make cloning?

If you have any other idea or methods to suggest it would be grate

My final target is production of avocados locally Zone 8 and Zone 9 by selection and observations from above mentioned varies

Thanks in advance

Modify message

Hi Irakli,

You might contact a grower closer to you. For example, Brokaw Nursery in Spain: https://www.viverosbrokaw.com/?lang=en

Thank you Greg

One more question, what is a minimum annual sunshine in hours for avocado ripening ?

Hi Irakli,

The more sun an avocado tree gets, the more fruitful it will be, in general. I know avocado trees that are on south-facing slopes (northern hemisphere) with unimpeded sunshine all day, all year long, and they grow fast and are extremely fruitful. Then I know avocado trees that are growing under the canopy of giant oak trees and they still produce fruit, but they produce far less.

Hi Greg. I love all your posts. Thank you for writing them. As for my question, I am about to move to a place that has a big yard and I want to try the 2 varieties for each season strategy. My plan is to pretty much do as you suggest with the Reed/ lamb combo then the Fuerte/ Pinkerton combo but I was interested in what you thought about a Jan Boyce/ Hass combo for spring. I live in Temecula closer to wine country. Thanks for your thoughts

Thanks, Walter. I think Hass and Jan Boyce should make a nice spring team. My guess is that Jan Boyce will taste prime a little earlier than Hass, and then Hass will last until the Reeds and Lambs are ready. I picked my last Hass yesterday and I also just ate the first Reed from my tree (a drop) that tasted decent.

Thanks Greg. The Reed at my current house started the year with 6 cados, 5 fell off over the last month. I they tasted pretty good. I’m probably going to pick the last one soon. Definitely before I leave.

I have another question now though. I’ve read several of your posts that mention the Fuerte as a finicky bearer. It seems like the further you are away from the beach the less reliable it is. Would a Fuerte be worth growing in temecula? The nights here can be somewhat chilly for most of the year. I really like the taste of the Fuerte but, if it doesn’t make fruit here than I’d rather have something else. What would you recommend to pair with Pinkerton for winter avocados in that situation?

Hi Greg. Still wondering if you’ve got another suggestion for a winter variety that will produce well in temecula. I think I can count on the Pinkerton to produce but I’m looking for one more variety.I’m thinking maybe Sir Prize? Mexicola? What else even ripens in the winter months

Hi Walter,